This chapter from Mastering Patient & Family Education: A Healthcare Handbook for Success focuses on the nurse’s primary role in planning and coordinating patient and family education.

“Improving world health through knowledge.”

–Sigma Theta Tau International

OBJECTIVES

- Explain the nurse’s role in leading patient and family education.

- Discuss the core components of the Marshall Personalized Patient-Family Education Model-Health System Approach (PPFEM-HSA) and highlight the specific actions that nurses need to take to achieve the learning goals.

- Recognize the different self-regulated learning strategies used by patients and caregivers.

Introduction

This chapter focuses on the nurse’s unique and important role as a leader in patient and family education. It emphasizes a paradigm shift toward forward thinking and includes systems thinking when it comes to planning and coordinating patient and family education. Age/developmentally appropriate population-health management and self-care management strategies are presented here, with a focus on patients from vulnerable populations, including pediatrics, patients with cognitive processing issues including traumatic brain injury, and gerontology.

Toward a New, Not-So-New, Paradigm

Why is it important for nurses to embrace a new paradigm in which they view patient and family education as a primary role function? Nurses have the power to shape their care environment (Ponte et al., 2007). In particular, bedside nurses are with the patient more than any other discipline, and out of all the healthcare providers, play the most critical role to observe, detect, advocate, and “ensure patients receive high-quality care” (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2015, para. 1).

“Nurses, in concert with other health professionals, need to adopt roles as care coordinators, health coaches and system innovators.” (The Institute of Medicine, 2011, p. 66)

One of the nurse’s core roles is coordination of care, with patient and family education being one of the most important elements, to ensure there is continuity of care across the continuum for all care settings (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2015). It’s fundamental for the nurse to know the difference among self-care, complex care, and population health management for patients. Understanding the principles and tools you might use as a coordinator of care for each of these, as well as how they might be applied in different settings across the continuum, is also key. Each of these is fundamentally different within the care-coordinator role.

One of the focuses of self-care is to ensure competency of the patient and/or family to carry out aspects of basic care of themselves, developing their knowledge of care tasks such as activities of daily living (ADLs), medication administration, and care of supplies or equipment necessary to meet their health needs. Engaging the patient is essential for the patient to demonstrate competency. How do you achieve this? The nurse must listen to the patient’s point of view, explore how the patient feels, and determine how confident the patient is to care for the problem.

The nurse must assess these issues about the patient and caregivers:

- What is their knowledge about the problem? (What do they know?)

- What are they already doing to address the issue/problem? What have they tried? (What do they know to do?)

- What is their feeling about the problem? (What do they feel?)

- What do they think could be done differently? (What do they think to change?)

- What matters to them?

You must ask these questions from both a short-term and long-term perspective, because the answers may be different.

Coordinating complex care involves being a health coach and helping patients navigate within and across the systems they must directly interact with to meet their health needs. Population health management is a higher level of aggregate coordination, and it involves assessing the needs of a specific patient population, analyzing population outcomes, and making adjustments in care. These changes will ultimately affect the population as a whole, but also the individual patient within the population.

In today’s dynamic healthcare environment, with its constant changes and new initiatives, healthcare team members, and specifically nurses, can often get lost in the shuffle of competing elements. Among all their other duties, nurses must remember their primary role as an educator. Common barriers that keep nurses from adopting this paradigm include the perception of lack of time, knowledge of how to teach, and a commitment and investing effort into patient education (Boswell, Pichert, Lorenz, & Schlundt, 1990; Carpenter & Bell, 2002).

Adopting a new paradigm involves thinking differently, as well as adopting and integrating behaviors for leading patient and family education within health systems into your practice as a nurse.

Self-Reflecting on and Assessing Your Competencies

How ready are you for change? The nurse’s role is a facilitator and clinical leader for patient and family education. According to the ANA Scope and Standards of Nursing Practice, Standard 5B, Health Teaching and Health Promotion, states, in part, “that the registered nurse employs strategies to promote health and a safe environment” (ANA, 2010, p. 10). The registered nurse:

- “Provides health teaching that addresses such topics as healthy lifestyles, risk-reducing behaviors, developmental needs, activities of daily living, and preventive self-care” (ANA, 2010, p. 41).

- “Uses health promotion and health teaching methods appropriate to the situation and the healthcare consumer’s values, beliefs, health practices, developmental level, learning needs, readiness and ability to learn, language preference, spirituality, culture, and socioeconomic status” (ANA, 2010, p. 41).

By your licensure as a professional nurse, you are obligated to these standards, which expect all nurses to play a significant role in patient and family education.

Do you take charge of your own career? Assuming accountability and taking responsibility for developing one’s competencies are critical and basic to being a professional. While it’s valid to say that some nursing professionals have a passion or propensity for patient and family education, every nurse must maintain a basic competency for educating patients and families. Nurses have a professional obligation and responsibility to perform the core functions of nursing. Regardless of the degree to which an individual nurse participates in each function, all of the functions come into play throughout our practice, including patient-family education.

The core competencies you must embody as a nurse are related to the following core functions:

- Understanding the patient and family educational process

- Coordinating care

- Reinforcing patient and family partnerships and engaging them

The healthcare team begins and ends with the patient (and family) as the core team member. Engaging patients in their own care and constructing the patient-clinician partnership determines in part how successfully the patient moves from illness to wellness (or in maintaining wellness).

Are you a good communicator? A nurse who educates others must learn to be a good communicator. Open and transparent communication is vital. It is a partnership of educating that involves give and take. You learn from the family and patient, and they learn from you the things they still need to know to provide the best care moving forward. Be conscious that the patient, parents, family, and friends are all invaluable resources. Everyone represents a resource at their own level.

Do you facilitate self-efficacy? Another core element of the nurse’s role is to facilitate the development of self-care or independence through teaching and education. This is key to the professional and therapeutic role of the nurse. Many clinicians develop close relationships with patients, especially those with chronic conditions, because they provide clinical care over extended periods of time. To facilitate independence, nurses must pay special attention to cultivating self-care as opposed to enabling dependence on clinicians and on the system.

When you deliver on these competencies, you’ll see various benefits to clinical care outcomes. The Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Triple Aim focuses on improving the patient experience of care (e.g., US CAHPS, patient experience/satisfaction), improving the health of populations (e.g., health functional status, morbidity and mortality), and reducing the per capita costs of healthcare (e.g., total costs per member per month, hospital and ED utilization rate) (IHI, 2015). Patient and family education not only directly contributes to each of these outcomes but is a necessity to enable them to occur.

The Nurse’s Role in Educating Patients and Families

As stated previously in this chapter, educating patients and families is fundamentally the most important role of the nurse. To achieve better learning outcomes, we’ll walk you through the core model components and highlight the specific actions that nurses need to achieve the PPFEM-HSA learning goals.

Using a Patient’s and Family’s Story

Starting with the patient’s and family’s story, Table 2.1, you are reminded to modify your instructional approach in a linguistically appropriate manner and to consider relevant age and developmental aspects, as needed. Also take into account the patient’s and family’s culture, because “concepts of illness, health, and wellness are part of the total cultural belief system. Culture is one of the organizing concepts upon which nursing is based and defined” (ANA, 1991, Para 3).

Thus, you must use the patient’s story to support knowledge-transfer by customizing the approach you take to each patient. This way, you:

- Build prerequisite/foundational knowledge.

- Structure content and simplify concepts (low to high level of abstraction).

- Select the right approach, e.g., text vs. visual (handouts, hands on, or pictures/graphics).

- Organize care routines with calendars (week/month), symbols (sun/moon), color codes, and daily events (breakfast, lunch, and dinner or when you first get up/right before you go to sleep).

- Plan for more time as needed to provide the instruction in small doses, yet more frequently.

Table 2.1 The Goals of the Marshall PPFEM, “Story” Component

|

|

Goals

|

Nurses Achieve Goals Through Collaboration

|

|

Personalize the healthcare experience

Identify health risk factors

Establish communication

Build relationship

Define expectations

Create self-awareness of coping

|

Understanding factors influencing health and care needs

Understanding country/regional perceptions of disease, conditions, or disability

Understanding expectations

Determining risk factors and degree of risk

Determining health and care needs

|

Once you determine the approach you’ll be taking, you need to partner with the patient and family to map out a plan.

Assessing a Patient’s Motivation and Desire for Wellness

You map out a plan by determining the learning goals, understanding exit coping strategies, and developing forward thinking, as shown in Table 2.2. Imagine the patient has the Aladdin lamp: Ask the patient or family, “regarding your situation, what would be your three desires?” This approach could be useful to share and understand the self-awareness of the patient and his expectations. It clarifies what you can do for and with him. This is also useful for understanding expectations that might be difficult to meet given the circumstances.

Show the general outline of a process. Create a plan and adjust it based on readiness. While they know it is important, most staff go in without a plan. If you are conscious about the process, you can understand your role because you are one part of a larger plan. And it is important to know when another person—be it a nurse or other specially trained educator—is needed or coming back at another time to continue the learning process.

For this negotiation to be successful and to successfully support self-regulation of learning, there are two important concepts that you need to consider:

- Self-reflection: First, learning to negotiate is influenced by the learner’s ability to accurately reflect and evaluate, which is essential to self-regulated learning. Self-reflection includes emotional reactions (such as stress or mood) and physiological indicators (such as heart rate or being tired) to make efficacy judgments (Bandura, 1986, 1997). For patients, self-reflection is the process of determining if they have the capacity to do what they are being asked to do. It also includes determining whether they feel like doing what they are asked to do. As a nurse, your role is to coach, mentor, and support opportunities for this process. This is where the value of interprofessional collaboration comes in, as other disciplines might need to support this aspect more directly in certain situations.

- Motivation: Secondly, learning to negotiate is influenced by the learner’s motivation. Motivational processes play out in the following ways. If the learner chooses a learning goal, how hard is that goal, and how hard will they work at it or how much “effort” will they invest in reaching the goal? Thus, learning to negotiate is pivotal because it happens at the beginning stage of goal setting, which lays the foundation for adherence to treatment plans. It is also why patients and families must be part of the process when choosing a treatment plan, because the goals linked to that plan are tied to a motivational process.

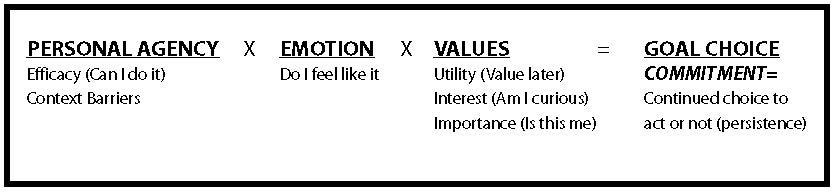

Clark’s (1997) Choice and Necessary Effort (CANE) model (see Figure 2.1) provides an easy way to connect three components—personal agency, emotion, and value. All three components must be in place for a learner to choose a goal. If a learner does not “feel like” working on a goal, they will not choose it unless they are able to create the value around it. Each of us sometimes face situations in which we don’t feel like doing something, but through self-talk and connecting to a greater purpose, we move forward with a goal.

Click to enlarge figure.

Figure 2.1 Clark’s Choice and Necessary Effort (CANE) model. Used with permission. Richard Clark © 1997

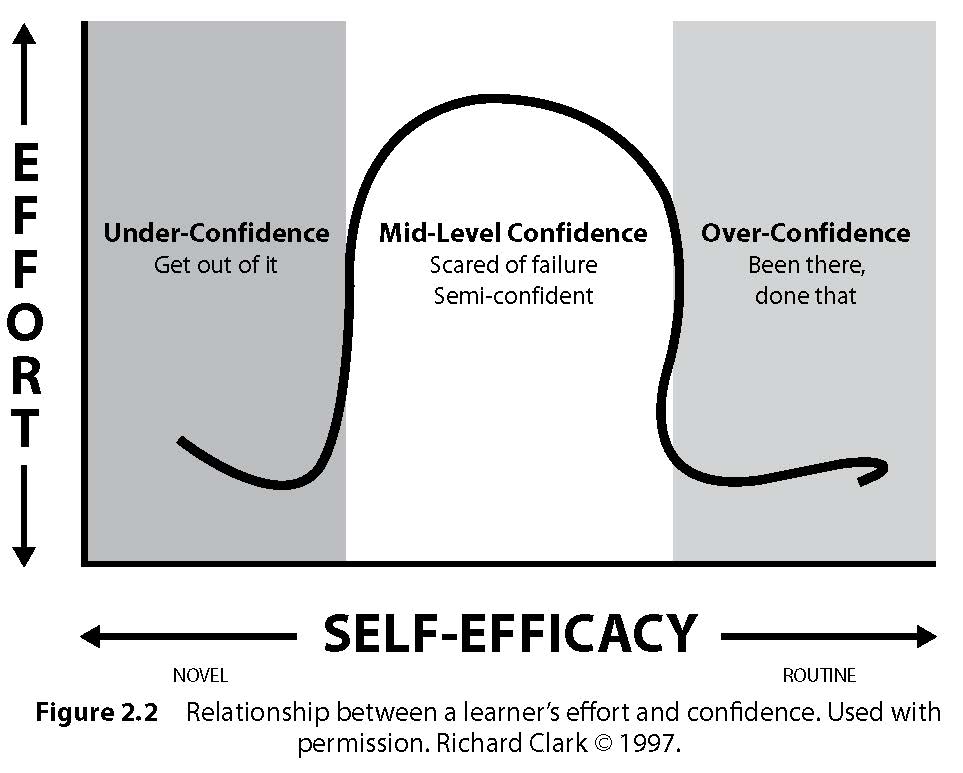

It is worth mentioning that a learner may over- or underestimate their efficacy levels. Figure 2.2 shows the relationship among the amount of effort a learner will invest, based on his level of confidence in completing a goal or learning a task. Effort is defined as the amount of new knowledge, in the form of cognitive strategies, that must be generated to achieve a goal (Clark, 1997). The information gathered from the story helps you know what the patient and family have previously done so you can appropriately guide the learner to a goal that will be enough of a stretch without seeming impossible. Hence the recommendation to set both short-term and long-term health goals.

Click to enlarge figure.

Figure 2.2 Relationship between a learner’s effort and confidence. Used with permission. Richard Clark © 1997.

Giving Patients Confidence in Their Own Abilities

In order to navigate learning needs, patients and families have to feel confident that they can take on healthcare providers and the health systems. They also have to feel confident that they can manage their health needs and actions to maintain health. Having confidence or higher efficacy is critical to navigate the healthcare journey. In Chapter 1 it was mentioned that efficacy is related to goal choice and effort. The higher one’s efficacy, the harder a goal will be selected and the more effort one will invest in achieving that goal. In looking at Table 2.2, these learning goals help with the structure and process needed to take charge of one’s health journey.

Table 2.2 Using the PPFEM to Achieve Learning Goals

|

|

Model Component

|

Goals

|

Nurses Achieve Goals Through Collaboration

|

|

Learning to negotiate healthcare learning needs

|

Adhere to treatment plan Create a patient/family/caregiver-provider partnership Establish interprofessional collaboration

|

Determining immediate goals Establishing forward thinking (hope and believing there is a future)

Identifying early coping mechanisms

Brokering interprofessional partnerships

|

|

Learning to navigate the health system and processes

|

Learn health system

Establish support plan and resources

Learn how to obtain information

Establish peer mentor and support network

|

Identifying locations and settings

Brokering support (peer level or groups)

Identifying resource needs including transportation and access to care

Helping to use the Internet and interactive patient-care technology for learning support Learning how to evaluate the resources

|

|

Learning to manage healthcare needs

|

Establish self-care management

Prepare for transition of care Promote care coordination Modify/strengthen coping strategies

Determine long-term goals

|

Identifying learning and self-care management needs

Preparing patient for self-care management

Facilitating knowledge-transfer Supporting transition of care across life continuum

Teaching new coping skills

|

|

Learning to maintain health

|

Maintain functional status Prevent disease progression Promote health and wellness

|

Reinforcing self-care management skills

Helping patients control the environment they live in Ensuring access to care Providing opportunities for positive coping strategies to be reinforced

Providing support across continuum of care

Assessing functional health status

Presenting transfer of care option

Providing education and development (schooling, training, etc.)

|

Whereas negotiation serves as an essential component for setting goals, successful navigation helps build efficacy, which is a critical foundation for applying knowledge and skills in managing care.

If you find that a patient has underestimated his efficacy, he may have adequate knowledge but does not realize that he knows how to do it. The patient might see himself as unable and/or see his environment as preventing success. You would see him avoid a task, get easily distracted, or try to find an honorable way out. This patient values the task at hand but does not invest enough effort.

Clark (1997) provides tips on what a nurse can do to help an under-confident patient engage. Start by reducing the challenge by focusing on the task, and point to prior knowledge if available. Nurses should:

- Provide daily goals

- Structure the task

- Provide procedural advice

- Attribute mistakes to effort (rather than ability)

- Show coping models

- Model positive mood

- Monitor and give feedback

If a patient overestimates her skill level, she may have adequate knowledge but treat novel tasks as routine and use the wrong approach to solving problems; if she fails or performs poorly, she then blames others (Clark, 1997). This might be due to her incorrectly perceiving a task or goal as familiar when it is in fact novel and requires much thought and effort to handle. This patient values the task but underestimates the effort needed to perform it.

Using the CANE concepts (Clark, 1997), you can help these kinds of patients by adjusting their belief about the goal or task. In these cases, nurses should:

- Show novelty and difficulty

- Prove that the current approach might lead to failure

- Attribute failure to effort

- Show peer performance

- Request a new approach

- Monitor progress closely

- Give feedback

Providing Access to Support Groups and Systems

Support groups and systems are critical to a patient’s success. Nurses can help support higher efficacy beliefs via support groups in two ways. First, through the use of “social persuasion” by telling patients or caregivers they’re capable of performing a goal or can meet a goal; this provides temporary or situational efficacy (Bandura, 1986, 1997). Unless social persuasion is followed by a positive experience, the influence is not long lasting (Bandura, 1986, 1997).

The second is to influence learners “vicariously” by brokering peer models and support through social models. This is a comparative element of self-reaction and is aided when models are perceived as similar to the learner (i.e., when the patient perceives the model group to be true peers) (Bandura, 1986, 1997). Patients increase their efficacy by observing and interacting with a “social model.” In this regard, always be thinking about the resources you can use for these types of experiences. The nurse is not the only resource of the educational process; the nurse is a facilitator and a supporter.

Using a patient’s peers as a resource and as part of the process is important. You should begin brokering these relationships early in the learning process. Peers provide different motivational benefits, including learning new coping skills.

Helping Patients and Families Find Information

Searching online for healthcare information shows initiative and active involvement in healthcare by the family or patient. Not all sources, however, are valid. Some are advertisements by corporations or special interests, so it is important to teach the family to search for reputable sources. It may be valuable to offer a list of some valid sources and to discuss what the family has found online. The discussion should be open and accepting of the initiative shown by the family, but also a careful examination of the sources, their relevance to the patient, and their scientific/medical value.

Maximizing Knowledge-Transfer Through Collaboration

At this point, you must focus on identifying and preparing for the learning need. This section addresses how you can maximize learning. You can structure a learning event to maximize knowledge-transfer. You have probably done this yourself when you hear the patient or family member has learning needs: You grab a handout or two and go in to start teaching. When you arrive at the room, you realize that what you brought with you, or thought you would do, won’t work. A key problem for nurses when it comes to patient and family education is not having a plan. As Carpenter and Bell say, “Patient education is approached best in an organized manner in which each education encounter, regardless of the length of time, is more likely to produce a quality session, thereby influencing patients to make positive changes in behavior” (2002, p. 157).

A learner’s efficacy is highly influenced by achieving mastery, which is tied to managing care needs. Mastery is defined as experiencing the actual completion of a goal/task (Bandura, 1986, 1997) and is considered the most effective form of influence on self-efficacy. It is important to note that failure can undermine efficacy unless a person has had the chance to build up enough resiliency through multiple successes. Mastery is also connected to motivated behavior and completion of goals.

You help patients achieve mastery through thoughtful planning in the way you design and organize the educational experience. We will cover foundational concepts about instructional design and information processing that serve as powerful tools that support self-directed learning. This is the pinnacle of knowledge-transfer, where you hand off what you know to the patients and families.

Although multiple learning theories and models exist, the goal of this chapter is to keep your attention focused on what matters most, which is having a plan.

Structuring the Learning

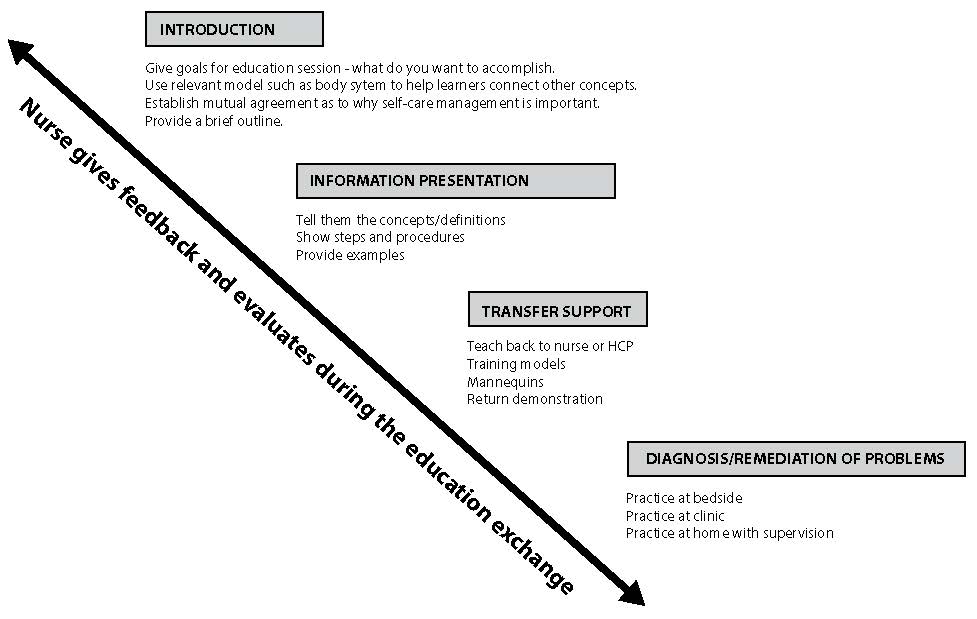

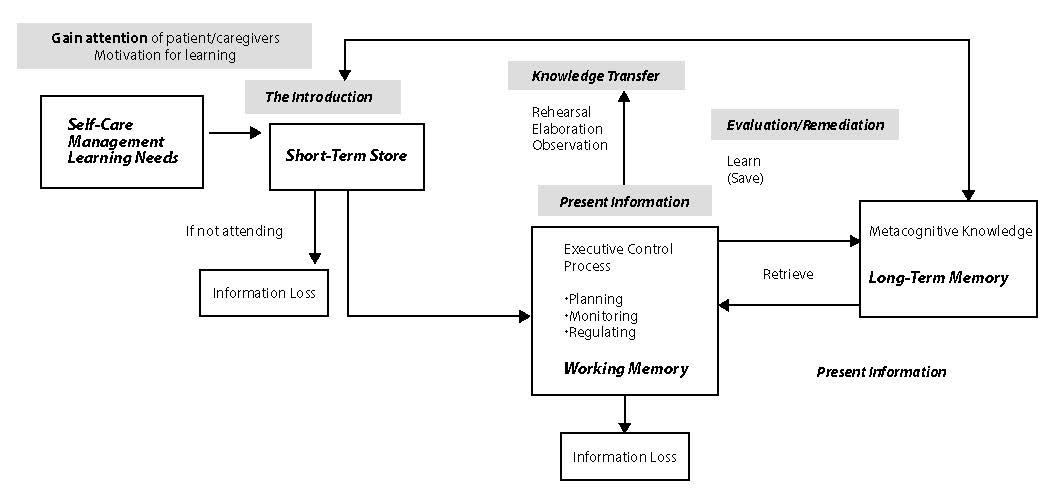

A simple way to remember how to organize and structure an educational experience draws from the evidence on cognition (how people process information). Figure 2.3 highlights the instructional design process. This is flexible enough to apply to both formal and informal education needs. For informal use, the bedside nurse would write notes to organize her approach or run through this mentally in preparation for education. That is the operative phrase… prepare in advance.

Start with an introduction by stating the learning goals, explain why they are important, and give a brief overview of what you will cover. Motivationally, this is a critical step, because the reason for needing to learn a particular task or skill may not be one the learner has “bought into.” As such, it is at this stage the nurse would also seek to understand the learner’s side of it and leverage that. Refer back to the CANE model to review the value component (utility, interest, and importance). It is also at this introductory phase that the nurse would propose a way for the patient to have a shared mental model of the concepts to be learned. For example, healthcare providers will start teaching about asthma medications, specifically relievers and controllers. The patient or caregiver leaves that encounter and heads home. Upon a return visit to the clinic, it is discovered that only one medication, the reliever, is being frequently used. Upon further exploration, the patient thought the nurse demonstrated the same thing. If the previous education started by using a shared mental model, the learner could then connect the condition (asthma) to the different types of medications needed to help bronchospasms (reliever) and reduce inflammation (controller). The simplest model to use is the lungs and how they work. Without this knowledge of what is “normal,” that learner cannot easily connect what happens with asthma.

Click to enlarge figure.

Figure 2.3 Using the instructional design process to plan PFE. Adapted from Gagne, Wagner, Golas, & Keller (2004).

Next, present or tell the learners the information starting with foundational concepts and then build to steps, procedures, and examples. Knowledge-transfer is supported by using tools and showing the learner how to do it. For mastery, the learner must have the opportunity to demonstrate or show you the steps. Employ the use of good communication and feedback to ensure they are confident. Highlight the aspects of the learning task they do well and show them the areas that need to be changed to the right step. This is part of practice and feedback, where your role is to evaluate their knowledge and skills for self-care management.

Connecting Structure to How People Process Information

The next concept that is important to understand is how learners process information. When you have a good understanding of this process, you’ll be able to work better with a variety of learners. Figure 2.4 provides an overview of how information is processed based on the work of Driscoll (1994).

Click to enlarge figure.

Figure 2.4 The basic information-processing model connected to the instructional design components. Adapted from Driscoll (1994).

The introduction component of your education is key to gaining the learners’ attention. They need this to help retain the information so it can become part of their future self-care management knowledge and skills toolkit. If not, the information is lost, because short-term memory is a temporary holding zone. To make information part of the long-term memory, the learner must use metacognition or higher-level “executive processing” to control learning. Executive processing includes planning, monitoring, and regulating. Planning is choosing the right strategies, approaches, and resources to meet one’s health goals. Monitoring is checking on the progress or status of a health goal. Regulating is one’s ability to adjust or organize the self-care environment.

A learner then uses other strategies to hang onto the information so it is accurate and available later. Learners rehearse, reorganize, or elaborate on the information to make the knowledge theirs. This is why the process of learners explaining back what they learned is valuable. It is also why nurses must afford every opportunity to have patients and families practice skills and share their knowledge during their healthcare journey. Keep in mind that many conditions and injuries greatly affect information processing and require a focused approach. A few strategies will be presented later in the chapter.

Helping Patients Maintain Their Health and Wellbeing

Setting and choosing goals is a small part of maintaining health and wellbeing. The greatest challenge lies in the long term. This is when choices are tested, when held up against time. This is where you as the nurse must be aware of and know how to address the concept of commitment. Commitment differs from choosing a goal in that people can choose many goals, but the actions leading to sustainably acting on that goal day after day, year after year, are unique to commitment. Commitment is the ability to keep working on a goal regardless of the distractions (Clark, 1997).

How do you determine if your patient and family are self-regulated learners? Maintaining health and wellbeing requires a daily recommitment to one’s goals. Table 2.3 provides examples of the words, actions, and language your patients, their family, and/or caregiver will use that give you an indication as to their degree of self-regulation. The nurse’s role is to help patients and caregivers develop strategies to increase self-regulatory processes, which lead to consistently performing self-care management behaviors.

This supports the use of metacognitive learning strategies (planning, monitoring, and organizing) that have been discussed in Chapter 1 and in a previous section in this chapter. The goal is that patients can connect their actions in the educational process with greater intent. In order to do this, they must gain greater awareness of their own actions and understand the intentions behind them.

TIP

Make one of your goals to commit to developing patients and families as future self-regulated learners. As such, it is important to recognize opportunities to coach, encourage, and mentor patients and families to use these strategies.

Table 2.3 Examples of Self-Regulated Learning Strategies for Patients and Caregivers

|

|

Strategy

|

Definition

|

Example

|

|

Self-evaluation

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated self-reflection and evaluations of their progress in meeting a goal or evaluating health status

|

“I checked over my weight loss chart to make sure I was on track.”

“I used my child’s asthma action plan to check David’s number from this morning, with the number the doctor wrote. Since it was lower, I gave him more medicine and called the doctor.”

|

|

Organizing and transforming

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated overt or covert re-arrangement of information they need to learn to improve learning

|

“Before I met with my doctor, I made an outline using the handout about what I needed to learn.”

|

|

Goal setting and planning

|

Statements indicating learner’s setting of health goals or sub-goals and planning for sequencing, timing, and completing activities related to those goals

|

“I started eating lower-fat foods 2 weeks before my surgery, and now I pace myself to eat a little butter each week.”

|

|

Seeking information

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated efforts to secure further task information from non-social sources when undertaking an assignment

|

“Before beginning the new chemotherapy, I went to the Cancer Society website to get as much information as possible concerning the topic.”

|

|

Keeping records and monitoring

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated efforts to record events or results

|

“I wrote down my peak flow numbers.”

“I keep a list of the questions I want to ask my doctor.”

|

|

Environmental structuring

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated efforts to select or arrange the physical setting to make meeting the learning goal easier

|

“To help with my asthma, I vacuum and keep the house dusted a few times a week.”

“I had a ramp built so I can get in and out of the house on my own.”

|

|

Self-consequating

|

Statements indicating a learner’s arrangement of rewards or punishments for success or failure

|

“If I keep my HbgA1c below 6.0, I will treat myself to a new outfit or movie.”

|

|

Rehearsing and memorizing

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated efforts to memorize material by overt or covert practice Types of rehearsal:

Maintenance rehearsal is the direct cycling of information in order to keep it active in short-term memory.

Elaborative rehearsal is relating the information to be remembered to other information to promote deeper processing.

|

“In preparing to take my father (or child) home from the hospital, I have to learn how to give IV medicines. I keep writing the order of what I’m supposed to do until I remember it.”

“After my nurse told me about the medicine, I explained what it was for and why I was taking it. I was able to tell her the difference between the two inhalers.”

|

|

Seeking social assistance

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated efforts to solicit help from (a) peers, (b) parent/family, and/or (c) healthcare providers

|

“If I have problems, I ask my mother [or friend] for help.”

|

|

Reviewing records

|

Statements indicating learner-initiated efforts to re-read (a) notes, (b) websites, and/or (c) documents from healthcare visits to prepare for interactions with healthcare providers

|

“When getting ready to see my doctor, I review my ____.”

|

Adapted from Zimmerman (1989).

In contrast to the examples of self-regulated learning strategies in Table 2.3, a patient lacking self-directed behavior makes statements indicating learning behavior that is initiated or driven by others, such as parents, friends, or healthcare providers. These statements (such as “I just do what the nurse or doctor tells me to do”) indicate that the learner has not internalized or bought into the goal.

Developing Population-Specific Strategies

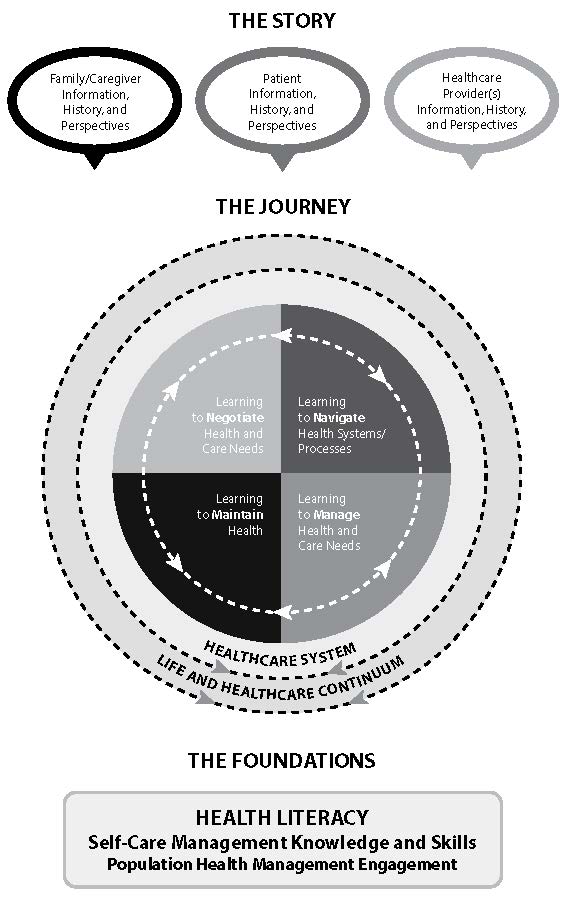

Patient-education strategies for three vulnerable and at-risk populations are explored next, using the Marshall PPFEM as a framework (see Figure 2.5).

Click to enlarge figure.

Figure 2.5 The Marshall PPFEM.

Patient-Family Education Applied to Pediatrics

Pediatrics is a challenging patient population due to the wide range of approaches you have to take. Although the patient is the focus of the healthcare experience, the family/caregivers become equally important in the journey.

Pediatrics is a challenging patient population due to the wide range of approaches you have to take. Although the patient is the focus of the healthcare experience, the family/caregivers become equally important in the journey.

Consider the “story” from the pediatrics perspective:

- Pediatric patients must be treated according to age and developmental needs, which are very different from infant to school-age to adolescent.

- Pediatric patients are not little adults; dosing of medication is different and approaches to healthcare teaching must be different than with adults.

- Pediatric care extends to 26 years of age.

- Young adulthood is an extremely vulnerable time. Young adults are still developing and must be approached in a way that considers that adult thinking may not be fully developed. They are at great risk for falling into coverage gaps, and this is critical for those with complex care needs.

Next, consider the “journey” from the pediatrics perspective. Recall that the journey includes negotiating health and care, navigating health systems and processes, managing health and care, and maintaining health.

In negotiating health and care from the pediatrics perspective:

- Engage the child at the appropriate developmental level.

- Address and engage the child as well as the parent.

- Toddlers often need a “broken record” response, with the consistent message repeated.

- Offer realistic choices such as “you can choose which medication to take first.”

- Keep instructions simple.

- Use playful songs, nursery rhymes, current movies, and other play to engage the child and build trust.

- Be truthful when talking about painful procedures or the taste of medications.

- Use eye contact and real words, even for infants, and pause to let the child respond.

- Watch for signs of overstimulation or stress, through body language with the infant or small child, who may turn away, close eyes, and sneeze. Watch for acting out in school-age or older children. You may see withdrawal in teens.

In navigating health systems and processes from the pediatrics perspective:

- The goal is to achieve developmental milestones, which may have to be modified due to illness/disabilities.

- Prolonged hospital stays can impact normal growth and development, so care must be given to optimize growth and development through special therapies.

- Younger children rely on parental support and guidance, whereas peer support is important to adolescents.

In managing healthcare from the pediatrics perspective:

- Education on proper nutrition, adequate sleep, and adequate time to play and exercise is important. Teenagers in particular need adequate sleep.

- Do not ask the child to “be brave,” but state that you understand if the child is in pain and do something to ease the pain.

- In the hospital setting, seek out Child Life professionals, who help children cope with procedures and let them be kids.

- Educating parents about medications or other care is necessary.

- Different disease processes require dietary adjustments, so enlist dietitian support.

In maintaining health from the pediatrics perspective:

- Medication adherence is problematic for adolescents with chronic diseases. They may rebel against the restrictions of the disease process, so using text messaging, social media support groups, or other peer support may help.

- Children do not realize their limitations, so safety is key. Keep medications out of reach, anchor tubing to keep it from being entangled, and cover any wounds or intravenous access sites.

The foundations of pediatrics-based education involve:

- Supporting the pediatric population with health literacy as well as mastery of knowledge and skills. For small children, or those with delays, the first transition in care is from healthcare provider to family. However, the children should always be included in teaching whenever possible. For younger children, use play to engage the child and let the child explore. For example, let the child hold an empty syringe or examine a tube, or have a doll with devices such as tubes or casts if the child has any devices. The child should be at the center of this activity, although the family needs special attention and education to become autonomous in caring for their child.

- Advancing the education as the child ages. Education should advance with the child’s development to maximize the child’s independent self-care, and the child should receive specialized, individualized teaching. When possible, encourage self-care to transition the pediatric patient to independent self-care. Encourage parents to embrace maximum independent self-care by the child so the family can optimize whatever growth and development is possible for this child. The goal is to achieve maximum functioning for the child. The parents may need special attention to allow this separation due to fears and feelings of protectiveness for the sick or impaired child.

Note that adolescence is a particular challenge, because this stage is naturally expressed in some opposition to control, desire to fit in with peers, and resentment against strict medical regimens such as medications or restrictions in diet or activity. Enlisting peer support can help, such as online support groups or camp activities.

Patient-Family Education Applied to Children and Adults with Cognitive Processing Issues

Cognitive processing issues present a challenge to patient educators. This is an issue found across the life span. In children, it may be due to congenital issues or events surrounding birth or due to accidents, brain traumas, or neurological diseases. In adulthood, it is often due to degenerative changes, including Alzheimer’s disease, which alters memory and cognition, or traumatic injury. While this section covers cognitive processing issues, PFE for traumatic brain injury will also be covered, because some of the same approaches are leveraged to facilitate knowledge-transfer.

Consider the “story” from the perspective of treating someone with a traumatic brain injury or other cognitive processing issue. The concept of “learning about previous health and care experiences current knowledge and skills” is essential (Lash, 2000). What makes traumatic brain injury unique regardless of age, for example, is the drastic change in the patient’s story in one moment’s time.

Next, consider the “journey” from the perspective of treating someone with a traumatic brain injury. Recall that the journey includes negotiating health and care, navigating health systems and processes, managing health and care, and maintaining health.

In negotiating health and care from the traumatic brain injury perspective:

- Developmental age will be different after the injury, depending on its severity.

- Patient’s developmental age may be less than the age in years.

- Capacities and cognition may change on a daily basis.

- Patient may be forgetful; short-term memory loss is not uncommon, so be patient, repeat with kindness, and avoid showing frustration.

- Patients may grieve loss of function and isolation, especially teenage patients, so optimize any visitors, texting, and online groups with supervision.

- Encourage others to interact with the patient when appropriate, when patient is not too tired, hungry, or upset.

- Family members will likewise grieve the loss of function, potentially the loss of personality and future hopes and dreams.

In navigating health systems and processes from the traumatic brain injury perspective:

- Sensorimotor capacities will be impacted.

- Patient may no longer be independent in any or all of activities of daily living.

- Patient may not be able to eat, swallow, urinate, or have bowel movements spontaneously or under their control.

- Goal is to maximize function for the individual with appropriate gradient expectations.

In managing health and care from the traumatic brain injury perspective:

- Therapists will teach you how to work with the patient to avoid inducing helplessness or atrophy from disuse, and, on the other hand, how to avoid frustrating the patient with unrealistic expectations.

- Many patients will need assistive/adaptive devices for mobility such as braces, casts, crutches, walkers, reachers, visual or hearing aids, or communication devices.

- Safety is key, because mobility deficits may make patient unable to sit/stand/walk as they could in their pre-injury status.

- Use simple words according to developmental age, not age in years.

- You may need to reword directions or communications to achieve understanding.

- Keep directions simple and to the point.

- Talk to the patient gently and clearly, maintaining eye contact.

- Patient may need constant monitoring to avoid injury.

- Patient may be agitated and combative, so safe handling is needed.

- Keep stimulation to a minimum, with a quiet environment and soft lighting.

In maintaining health from the traumatic brain injury perspective:

- TBI patients need rest and sleep.

- TBI patients need good nutrition and may have eating difficulties.

- Skin care is important if the patient is not continent.

- Bladder and bowel functions may not be normal; careful assessment and monitoring of intake and output is vital; patient may require bowel training, catheterization.

- Move toward normalizing life, accepting the new baseline for the patient, and optimizing all function.

The foundations of PFE for traumatic brain injury patients are as follows.

Health Literacy

Health literacy by its very definition can be a significant issue in the brain-injured patient. To have health literacy, one must, to some degree, have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand health information. One also must be able, on some level, to make health decisions based on the information one has and understands. A brain-injured patient can have varying degrees of memory loss, confusion, agitation, and issues with judgment, among other behavioral changes. A family and caregiver assessment is a big part of any complete learning assessment, but here it becomes a crucial part in the planning of education and goal setting.

The gradient approach to competent literacy—with intermittent and consistent assessments of the positive steps in the learning process—is very important here, because the learning process can be slow in this population, resulting in discouragement and setbacks along the way. Focusing repeatedly on the gains made in any education can go a long way, but especially here, to promote functional literacy.

Self-Care Knowledge and Skills

In patients with cognitive dysfunction, self-care skills must not only be thoroughly assessed, but the overall goal must be allowing and promoting as much safe independence as possible. Along with the patient assessment, assess patient support both in the home and in the community. A person with a brain injury can sometimes remember parts of their pre-injury life and abilities, and frustration is common. Again, it is vital to engage the family for support and promote positive feedback; repetitive instruction and reinforcement of gains is key. This will help to preserve motivation and safe independence.

A multidisciplinary team approach that leverages many areas of expertise is absolutely necessary to put in the overall plan and implementation. It is important to address all areas of deficit and provide an appropriately planned gradient education program that can engage the patient, family, and caregivers to meet their maximum function and potential.

Population Health Engagement

There are support groups for all kinds of issues, but not all are accessible when and where they are needed. The coordinating professionals on the multidisciplinary team are responsible for finding and sharing the appropriate resources so that those groups can be utilized.

Community outreach projects can assure public education on the pertinent issues and connect people needing services and support with those delivering it. This can make a difference in the progression toward changing the paradigm to a forward-thinking plan across the entire continuum of care and responsibility.

Patient-Family Education Applied to the Elderly (Gerontology)

An elder’s story is rich with life experiences and history. Reflection on a lifetime of experiences, career, and travels shapes who they are. Keep in mind elders’ variation in health status, because the term “elder” does not equate to unhealthy or inactive. However, the body does experience changes as we age, and common issues for the elderly population include vision, hearing, and mobility (see Figure 2.6).

Next, consider steps in the “journey” from the perspective of gerontology.

In negotiating health and care from the perspective of gerontology:

- Be sure to account for patients’ outlook on life and living, including the importance of family and friends.

- Set realistic goals and be sure to include family members in the process.

In navigating health systems and processes from the perspective of gerontology:

- Modify activity such as driving, socialization, and engagement determined by baseline function.

In managing healthcare from the perspective of gerontology:

- Encourage patient to be as engaged as possible.

- Although the patient is an important focus for patient and family education, this is where the transition back to family and caregivers becomes important. As in the pediatric population, the child begins to learn routines as part of care transition, so does the transition of care need to be brought back to the family of the elderly.

- Educate caregivers on where/how to support their loved ones.

- Educate caregivers on how to maintain self-care.

- Teach new coping skills. In part, this is derived from the level of forward thinking in play. Self-determination is a critical component.

In maintaining health from the perspective of gerontology:

- Ensure there are transportation services to keep appointments.

- Set up communication processes, including technology, to remain connected to providers and health system.

- Maintain solid community and family support and network.

The foundations of PFE for gerontology patients are as follows:

Health Literacy

In gerontology, it is important to dispel the myth that behaviors are set and cannot be changed. It is very possible when the educational process is well paced and individualized to change the way things are done (Best, 2001). Tools are needed for planning and organizing things like the daily routine and medication regimens (Shen et al., 2006). Technology tools can be used here, because many elderly people are now engaged with some form of technological device. You must be cognizant that changes can be both upsetting and even dangerous if not monitored until the new regimen is solidly in place. As with TBI patients, you may encounter impaired decision-making and judgment with elderly patients (Centeno, 2011). The difference here is that they are more likely to worsen over time, requiring reassessment and new goal setting.

Self-Care Knowledge and Skills

Here, maintenance of independence is the goal. A threat to self-care can be upsetting to your patient, because it creates the feeling of a loss of independence. It is important to assess for safety factors and encourage support for the areas deemed the most unsafe if performed solely by the patient, but it is also important to find and maintain areas where self-care can be performed safely.

Focus should also be on safe independence, as in the TBI patient, because falls can be common here and lessen independence by causing setbacks in function. It is important to recognize that muscle weakness and loss of muscle tone is not necessarily a function of aging, but more a function of inactivity. It is a vicious cycle, because inactivity breeds weakness and that in kind produces more inactivity. A well-paced and consistent exercise program is key to preserve tone and strength and prevent injury due to falls. According to the CDC website, “strengthening exercises, when done properly and through the full range of motion, increase a person’s flexibility and balance, which decrease the likelihood and severity of falls. One study in New Zealand in women 80 years of age and older showed a 40% reduction in falls with simple strength and balance training” (CDC, 2011, paragraph 5).

Patient communication skills are also important to assess, because the patient may be able to communicate to other caregivers some basic cares that are needed when they are unable to perform them safely on their own. This piece can be crucial to foster the idea of independence, because the patient, from his own level of knowledge, may be able to direct the action of those things that he cannot do by himself. The key here being engagement of the patient with his care and with his caregivers based upon his level of cognition and ability.

Population Health Engagement

Connecting to one’s health system and preventing isolation is an important part of health and wellbeing. This can be accomplished via community groups and through the use of social media. Facebook can be a wonderful way to keep family connected from around the world. Skype and other Internet-based tools are good to support emotional health. The responsibility of the professionals on the care team is educating, coordinating, and facilitating the connection between the aging patient and the world around them. Connection is vital to maintaining the feeling of self-worth.

Conclusion and Key Points

One of the most important nursing roles is in educating the patient and family. This component is directly responsible for influencing health outcomes. Yet, when it comes down to it, medication administration and other task-related aspects of a nursing professional’s job often overshadow these priorities. How do you shift your paradigm as a nursing professional so you can simultaneously serve the needs of the moment and of the future?

First, you must become an active and accountable exchange agent in educational activities and in the knowledge-transfer process. This means being willing to “let go of” and “hand off your knowledge” to the patient and family. To make it easy to remember the educational priorities, we leave you with the Five Rights of Patient-Family Education.

“The Five Rights of Patient-Family Education: The Right Approach (the Story) aimed at the Right Context (Continuum of Care) with the Right Content (Health Literacy) using the Right Methods (Self-Care Management Knowledge and Skills) followed by the Right Support (Population Health Engagement).”

Second, you need to adopt a broader framework for patient and family education that accounts for the current setting but within a global context. This includes ensuring that the treatment plans reflect the setting where the patients and families will continue their care after your involvement. For example, you plan a rehabilitation program for a child from a low-income country.

Finally, consider your role in shaping your own healthcare system and take into account that this perspective could change greatly and thus could influence the social, political, and cultural approach. This impacts the sustainability of the educational tools and resources available for patients and families. This may be one of the most important messages, that while focusing on improving health and wellbeing of people, nurses turn the PPFEM toward creating a health system that actually supports patients and families. In some cases, this focus should be a priority over the personal perspective (family, patient, and provider) that the HCP interprets as a professional.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (AHRQ). (2015). Nursing and patient safety. Retrieved from

psnet.ahrq.gov/primer.aspx?primerID=22

American Nurses Association. (2010). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice. (2nd ed.). Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association.

Bandura, A. (1986). The social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

Best, J. T. (2001). Effective teaching for the elderly: Back to basics. Orthopedic Nurse, 20(3), 46–52.

Boswell, E. J., Pichert, J. W., Lorenz, A. L., & Schlundt, D. G. (1990). Training health care professionals to enhance their patient teaching skills. Journal of Nursing Staff Development, 6(5), 223–239.

Carpenter, J., & Bell, S. (2002). What do nurses know about teaching patients? Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 18(3), 157–161.

Centeno, J. (2011). Methods of teaching and learning of the elderly: Care in rehabilitation.

CJNI: Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 6(1), Article Two. Retrieved from

http://cjni.net/journal/?p=1147

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011). Why strength training? Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/growingstronger/why/index.html

Clark, R. E. (1997, November). The CANE model of motivation to learn and to work: A two-stage process of goal commitment and effort. Paper presented at the University of Leuven, Belgium.

Driscoll, M. (1994). Psychology of learning for instruction. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, Inc.

Gagne, R., Wager, W., Golas, K., & Keller, J. (2004). Principles of instructional design. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). (2015). The IHI Triple Aim. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/engage/initiatives/TripleAim/

Pages/default.aspx

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The Future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

Lash, M. (2000). Teaching strategies for students with brain injuries. TBI Challenge!, 4(2). Retrieved from www.biausa.org/LiteratureRetrieve

.aspx?ID=48657

Ponte, P. R., Glazer, G., Dann, E., McCollum, K., Gross, A., Tyrrell, R., … Washington, D. (2007). The power of professional nursing practice—An essential element of patient and family centered care. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 12(1), Manuscript 3.

Shen, Q., Karr, M., Ko, A., Chan, D. K., Khan, R., & Duvall, D. (2006). Evaluation of a medication education program for elderly hospital in-patients. Geriatric Nurse, 27(3),184–92. Retrieved from http://hospitalmedicine.ucsf.edu/improve/literature/

discharge_committee_literature/med_reconciliation/

evaluation_of_medication_education_

program_for_elderly_hospital_

inpatients_shen_geriatr_nurs.pdf

Zimmerman, B. (1989). A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 329–339.

Lori C. Marshall, PhD, MSN, RN, isadministrator of Patient Family Education and Resources at Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

Immacolata Dall’Oglio, RN, MSN,isa manager in the Professional Development, Continuing Education, and Nursing Research Unit at Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital IRCCS in Italy.

David Davis, RN, MN, is vice president and chief quality officer at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

Gloria Verret, RN, BSN, CPN, is a patient family educator and clinical nurse at Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

Tere Jones, RN, CPN, is nurse care manager for Complex Care Service at Children's Hospital Los Angeles.