Chapter 4 of Mastering Precepting: A Nurse's Handbook for Success (Second Edition) explores core precepting concepts that form the foundation of effective, safe nursing practice.

"The most important practical lesson that can be given to nurses is to teach them what to observe, how to observe, what symptoms indicate improvement, what the reverse, which are of importance, which are of none, which are evidence of neglect and of what kind of neglect.”

—Florence Nightingale

OBJECTIVES

- Understand development of competence

- Understand critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment and how to help preceptees develop each skill

- Understand the development of preceptee confidence

- Understand core concepts of nursing practice

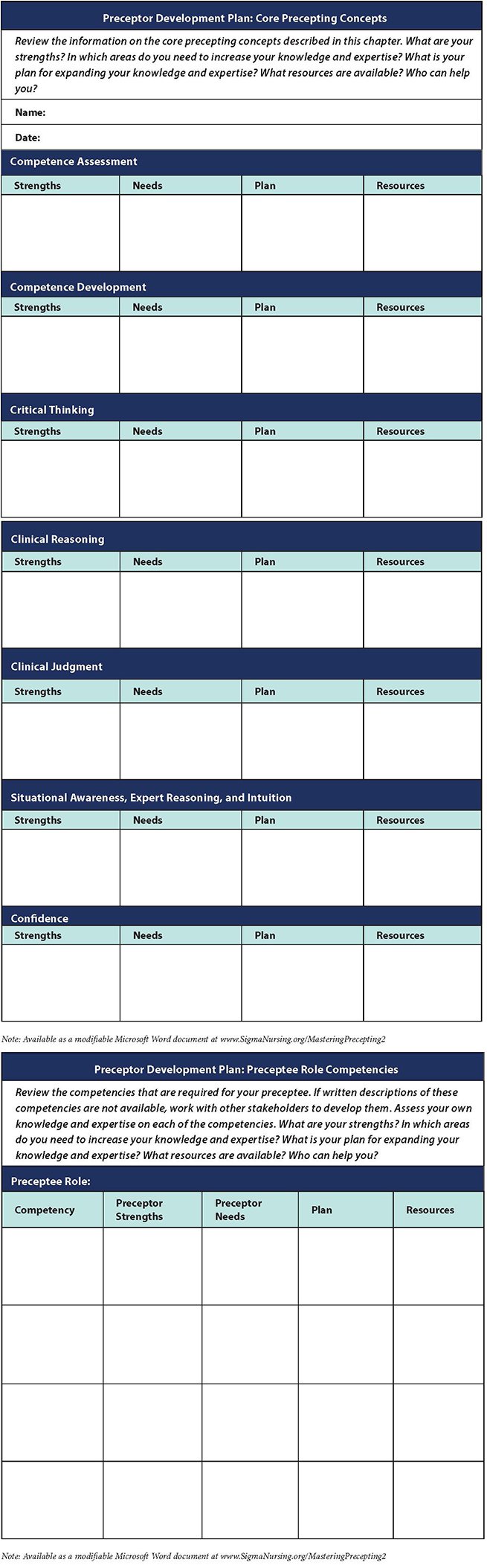

At the heart of any precepting experience is the development of competence; the development of ability and expertise to effectively utilize that competence; and the confidence to take action when needed. Combined with other core precepting concepts, these form the foundation of effective, safe nursing practice.

Competence

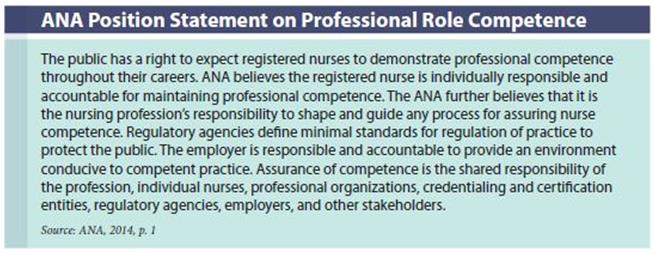

Professional competence is required of all registered nurses (RNs). Although we mostly talk about clinical competence for nurses, all nursing roles and positions require competence. The purposes of ensuring the competence of nurses are to protect the public (the primary purpose), advance the profession, and ensure the integrity of the profession.

Professional competence is required of all registered nurses (RNs). Although we mostly talk about clinical competence for nurses, all nursing roles and positions require competence. The purposes of ensuring the competence of nurses are to protect the public (the primary purpose), advance the profession, and ensure the integrity of the profession.

Competence is included in

Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice: “The registered nurse seeks knowledge and competence that reflects current nursing practice and promotes futuristic thinking” (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2015b, p. 5) and in the

Code of Ethics: “The nurse owes the same duties to self as to others, including the responsibility to promote health and safety, preserve wholeness of character and integrity, maintain competence, and continue personal and professional growth” (ANA, 2015a, p. 73). In addition, the ANA Position Statement on Professional Role Competence (ANA, 2014) defines competence and competency and identifies principles for addressing competence in the nursing profession (see below).

The ANA (2014) defines a

competency as “an expected level of performance that integrates knowledge, skills, abilities, and judgment” (p. 3). Knowledge, skills, ability, and judgment are defined as follows (ANA, 2014, p. 4):

- Knowledge encompasses thinking; understanding of science and humanities; professional standards of practice; and insights gained from context, practical experiences, personal capabilities, and leadership performance.

- Skills include psychomotor, communication, interpersonal, and diagnostic skills.

- Ability is the capacity to act effectively. It requires listening, integrity, knowledge of one’s strengths and weaknesses, positive self-regard, emotional intelligence, and openness to feedback.

- Judgment includes critical thinking, problem-solving, ethical reasoning, and decision-making.

Requirements for competence and competency assessment have been established by national nursing and nursing specialty organizations, state boards of nursing credentialing boards, and statutory and regulatory agencies. The presence (or absence) of competency can also be a legal issue.

The ANA Position Statement on Professional Role Competence states, “Competence in nursing practice must be evaluated by the individual nurse (self-assessment), nurse peers, and nurses in the roles of supervisor, coach, mentor, or preceptor. In addition, other aspects of nursing performance may be evaluated by professional colleagues and patients/clients” (ANA, 2014, p. 5). Competence is not about checking items off a list. In fact, the frequent use of terms such as “competency checklist” and “checking off preceptees” devalues the work required to develop and maintain competence and makes the process of validating competence sound as if it requires little thought—that it is merely an inconsequential nuisance and a documentation chore to be completed as quickly as possible. Nothing could be further from the truth. The validation of competence is one of the most critical elements to ensure safe, high-quality patient care and competent role performance.

Competence Development

Seeking to better understand the development of competency, the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) completed a qualitative longitudinal (5-year) study of a national sample of nurses from 2002–2008 (Kearney & Kenward, 2010). By the end of the fifth year, nurses had identified and demonstrated five characteristics of competence:

- Juggling complex patients and assignments efficiently

- Intervening for subtle shifts in patients’ conditions or families’ responses

- Having interpersonal skills of calm, compassion, generosity, and authority

- Seeing the big picture and knowing how to work the system

- Possessing an attitude of dedicated curiosity and commitment to lifelong learning

Participants described how competence developed and changed over time. Also of interest was how the development of competency affected their career plans and job satisfaction. Kearny and Kenward (2010) note:

Those who continued to feel insecure in their ability to efficiently identify and respond to important downturns in patients’ conditions in a high-acuity environment, who continually felt beaten down in their attempts to get resources and help for patients from fellow nurses, and/or who believed physicians did not listen to them or respect them appeared most likely to change jobs to less complex or less acute settings or to leave nursing. (p. 13)

This study clearly has implications for preceptors. Nurses’ career decisions and job satisfaction are both affected by how well they develop competence, especially for less experienced nurses.

Conscious Competence Learning

The concept of

conscious competence learning is a description of how individuals learn new competencies. The concept serves to remind us that learning a competence happens in stages. The stages of the conscious competence as described by Howell (1982) and expanded on by Cannon, Feinstein, and Friesen (2010) include unconscious competence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence, and unconscious competence.

-

Unconscious incompetence—The individual seeks to solve problems intuitively with little or no insight into the principles driving the solutions. This stage is especially dangerous with novices. When NGRNs first begin professional practice or experienced nurses move into a new role, they often don’t know what they don’t know. Preceptors have to be especially vigilant with a preceptee at this level.

-

Conscious incompetence—The individual seeks to solve problems logically, recognizing problems with their intuitive analysis, but not yet knowing how to fix them. This awareness— of knowing what you don’t know—can affect confidence. Preceptors can help preceptees in this level understand what they are expected to know at this point vs. what they will learn in the future.

-

Conscious competence—As skills are acquired, individuals become more confident but need to realize that the skills have not yet become automatic. They are not yet ready to spontaneously transfer the concepts of the skill to new situations. Preceptors need to help preceptees see how the concepts transfer from one situation to another.

-

Unconscious competence—At this level, skills become second nature and are performed without conscious effort. Skills can be adapted creatively and spontaneously to new situations. You know it so well, you don’t think about it. The challenge in this level is to not become complacent and be closed to new ways of doing things.

A fifth level of conscious competence learning—reflective competence—has been suggested (Attri, 2017). It involves an awareness that you’ve reached unconscious competence; analyzing and being able to articulate how you got there well enough to teach someone else to reach that level and opening yourself to the need for continuous self-observation and improvement.

This concept supports adult learning theory concerning learner readiness in the assertion that individuals develop competence only after they recognize the relevance of their own incompetence. It also blends easily with the levels in Benner’s Novice to Expert model.

Competency Outcomes and Performance Assessment (COPA) Model

Lenburg (1999) developed the Competency Outcomes and Performance Assessment (COPA) model. She describes it as “a holistic but focused model that requires the integration of practice-based outcomes, interactive learning methods, and performance assessment of competencies” (Lenburg, 1999, para. 2).

The basic framework of the model consists of four guiding questions (Lenburg, 1999):

-

What are the essential competencies and outcomes for contemporary practice? Identify the required competencies and word them as practice-based competency outcomes.

- What are the indicators that define those competencies? Only identify the behaviors, actions, and responses mandatory for the practice of each competency.

- What are the most effective ways to learn those competencies?

- What are the most effective ways to document that learners and/or practitioners have achieved the required competencies? Develop a systematic and comprehensive plan for outcomes assessment.

Eight core practice competency categories define practice in the COPA model (Lenburg, 1999):

- Assessment and intervention skills

- Communication skills

- Critical thinking skills

- Human caring and relationship skills

- Management skills

- Leadership skills

- Teaching skills

- Knowledge integration skills

In the COPA model, learner performance is assessed against a predetermined standard after the learning and practice have occurred. Lenburg (1999) notes how important it is to separate these activities— assessing versus learning/practicing—to keep the focus of each clear. The learner is then better able to concentrate on learning, and the preceptor can concentrate on teaching and coaching during the learning and practice periods, rather than both trying to split their attention and their purposes between learning and assessing and, perhaps, one not always knowing the focus of the other.

Lenburg (1999) has found that assessments are most effective when they are designed and implemented based on 10 basic concepts: examination, dimensions of practice, critical elements, objectivity, sampling, acceptability, comparability, consistency, flexibility, and systematized conditions.

Wright Competency Model

The Wright Competency Assessment Model is an outcome-focused, accountability-based approach that is used in many healthcare organizations. The following principles form the foundation of the model (Wright, 2015, p. 5):

- Select competencies that matter to both the people involved and to the organization.

- Competencies should reflect the current realities of practice, be connected to quality improvement data, be dynamic, and be collaboratively selected.

- Competency selection itself involves critical thinking.

- Select the right verification methods for each competency identified.

- Clarify the roles and accountability of the manager, educator, and employee in the competency process.

- Employee-centered competency verification creates a culture of engagement and commitment.

The model is grounded in three concepts—ownership, empowerment, and accountability (Wright, 2005):

- In ownership, competencies are collaboratively identified and are reflective of the dynamic nature of the work.

- Empowerment is achieved through employee-centered verification in which verification method choices are identified and appropriately match the competency categories.

- In accountability, leaders create a culture of success with a dual focus—focus on the organizational mission and focus on supporting positive employee behavior.

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is an essential competency for nurses to provide safe and effective care (Berkow, Virkstis, Stewart, Aronson, & Donohue, 2011). Alfaro-LeFevre (2017) says that critical thinking is “deliberate, informed thought” (p. 2) and that the difference between thinking and critical thinking is control and purpose. “Thinking refers to any mental activity. It can be ‘mindless,’ like when you’re daydreaming or doing routine tasks like brushing your teeth. Critical thinking is controlled and purposeful, using well-reasoned strategies to get the results you need” (p. 5).

Jackson (2006, p. 4) notes that three themes are found within all definitions of critical thinking: “the importance of a good foundation of knowledge, including formal and informal logic; the willingness to ask questions; and the ability to recognize new answers, even when they are not the norm and not in agreement with pre-existing attitudes.” Chan (2013), in a systematic review of critical thinking in nursing education, found that despite there being varying definitions of clinical thinking, there were some consistent components: gathering and seeking information: questioning and investigating; analysis, evaluation, and inference; and problem-solving and the application of theory. The principles of skepticism and objectivity underlie critical thinking (Chatfield, 2018). Objectivity includes recognizing and dealing with both conscious and unconscious bias.

Critical Thinking—A Philosophical Perspective

In 1990, the American Philosophical Association conducted a Delphi study of an expert panel to define critical thinking and to identify and describe the core skills and dispositions of critical thinking. The expert panel, led by Peter Facione (1990), defined critical thinking to be a pervasive and deliberate human phenomenon that is the “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based” (p. 2). The core skills and sub-skills identified by the expert panel are shown in Table 4.1.

According to the American Philosophical Association Delphi Study, the affective dispositions of critical thinking (approaches to life and living) include (Facione, 2011):

- Inquisitiveness with regard to a wide range of issues

- Concern to become and remain generally well informed

- Alertness to opportunities to use critical thinking

- Trust in the processes of reasoned inquiry

- Self-confidence in one’s own ability to reason

- Open-mindedness regarding divergent world views

- Flexibility in considering alternatives and opinions

- Understanding of the opinions of other people

- Fair-mindedness in appraising reasoning

- Honesty in facing one’s own biases, prejudices, stereotypes, and egocentric or sociocentric tendencies

- Prudence in suspending, making, or altering judgments

- Willingness to reconsider and revise views where honest reflection suggests that change is warranted

The dispositions to specific issues, questions, or problems include (Facione, 2011):

-

Clarity in stating the question or concern

- Orderliness in working with complexity

- Diligence in seeking relevant information

- Reasonableness in selecting and applying criteria

- Care in focusing attention on the concern at hand

- Persistence though difficulties are encountered

- Precision to the degree permitted by the subject and the circumstance

Critical Thinking in Nursing

Facione and Facione (1996) suggest that to observe and evaluate critical thinking in nursing knowledge development or clinical decision-making, you need to have the thinking process externalized by being spoken, written, or demonstrated. For preceptors, this means having preceptees externalize their thinking processes. Preceptors must also be able to externalize their own critical thinking to role model critical thinking for preceptees.

Paul, the founder of the Foundation for Critical Thinking, and Heaslip note, “Critical thinking presupposes a certain basic level of intellectual humility (i.e., the willingness to acknowledge the extent of one’s own ignorance) and a commitment to think clearly, precisely, and accurately and, in so far as is possible, to act on the basis of genuine knowledge. Genuine knowledge is attained through intellectual effort in figuring out and reasoning about problems one finds in practice” (Paul & Heaslip, 1995, p. 41). Expert nurses, say Paul and Heaslip, “can think through a situation to determine where intuition and ignorance interface with each other” (p. 43).

Building on the work of Facione and the American Philosophical Association Delphi study, Scheffer and Rubenfeld (2000) conducted a Delphi study of international nursing experts (from 27 U.S. states and eight countries) to develop a consensus statement of critical thinking in nursing. The result of the study was a consensus statement and identification of 10 affective components (habits of the mind) and seven cognitive components (skills) of critical thinking in nursing.

Critical thinking in nursing is an essential component of professional accountability and quality nursing care. Critical thinkers in nursing exhibit these habits of the mind: confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, open-mindedness, perseverance, and reflection. Critical thinkers in nursing practice the cognitive skills of analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting and transforming knowledge (Scheffer & Rubenfeld, 2000, p. 357).

Precepting Critical Thinking

Berkow and colleagues (2011) note that identifying and providing feedback on specific strengths and weaknesses is the first step to help nurses meaningfully improve their critical thinking skills. They interviewed more than 100 nurse leaders from academia, service settings, and professional associations and developed a list of core critical-thinking competencies in five broad categories: problem recognition, clinical decision-making, prioritization, clinical implementation, and reflection. Each of the categories has detailed competencies.

Alfaro-LeFevre (1999) developed a list of critical-thinking key questions that can be used by a preceptor to help preceptees learn how to think critically:

- What major outcomes (observable results) do I/we hope to achieve?

- What problems or issues must be addressed to achieve the major outcomes?

- What are the circumstances (what is the context)?

- What knowledge is required?

- How much room is there for error?

- How much time do I/we have?

- What resources can help?

- Whose perspectives must be considered?

- What’s influencing my thinking?

In addition, Alfaro-LeFevre (1999) offers suggestions on thinking critically about how to teach others:

- Be clear about the desired outcome.

- Decide what exactly the person must learn to achieve the desired outcome and decide the best way for the person to learn it.

- Reduce anxiety by offering support.

- Minimize distractions and teach at appropriate times.

- Use pictures, diagrams, and illustrations.

- Create mental images by using analogies and metaphors.

- Encourage people to remember by whatever words best trigger their mind.

- Keep it simple.

- Tune into your learners’ responses; change the pace, techniques, or content if needed.

- Summarize key points.

Preceptors can also use role-playing, case studies, reflection, and high-fidelity patient simulation to teach clinical thinking.

Clinical Reasoning

Tanner (2006) defines

clinical reasoning as “the processes by which nurses and other clinicians make their judgments, and includes both the deliberate process of generating alternatives, weighing them against the evidence, and choosing the most appropriate, and those patterns that might be characterized as engaged, practical reasoning (e.g., recognition of a pattern, an intuitive clinical grasp, a response without evident forethought)” (pp. 204—205).

Tanner (2006), in reviewing research on nurses and reasoning, found three interrelated patterns of reasoning that experienced nurses use in decision-making:

- Analytic processes—Breaking a situation down into its elements; generating and systematically and rationally weighing alternatives against the data and potential outcomes.

- Intuition—Immediately apprehending a situation (often using pattern recognition) as a result of experience with similar situations.

- Narrative thinking—Thinking through telling and interpreting stories.

Facione and Facione (2008) discuss research in human reasoning that has found evidence of the function of two interconnected “systems” of reasoning. System 1 is “reactive, instinctive, quick, and holistic” and often “relies on highly expeditious heuristic maneuvers which can yield useful response to perceived problems without recourse to reflection” (Facione & Facione, 2008, p. 4). System 2, on the other hand, is described as “more deliberative, reflective, analytical, and procedural” and is “generally associated with reflective problem-solving and critical thinking” (p. 4). They note that the two systems never function completely independently and that, in some cases, the two systems actually offer somewhat of a corrective effect on each other. In fact, they say, “Effectively mixing System 1 and System 2 cognitive maneuvers to identify and resolve clinical problems is the normal form of mental processes involved in sound, expert critical thinking” (p. 5).

Simmons, Lanuza, Fonteyn, Hicks, and Holm (2003) investigated clinical reasoning of experienced (2–10 years) medical-surgical nurses. They found that the nurses used a number of thinking strategies (heuristics) that consolidated patient information and their knowledge and experience to speed their reasoning process. The most frequently used heuristics were (Simmons et al., 2003):

- Recognizing a pattern or an inconsistency in the expected pattern

Judging the value of the information about which they were reasoning

- Providing explanations for why they had reasoned as they had

- Forming relationships between data

- Drawing conclusions

Clinical Judgment

Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment are interrelated concepts (Victor-Chmil, 2013). Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are processes that lead to the outcome of clinical judgment (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2017). Facione and Facione (2008) describe the relationship in this way: “critical thinking is the process we use to make a judgment about what to believe and what to do about the symptoms our patient is presenting for diagnosis and treatment” (p. 2).

Tanner (2006) defines clinical judgment to mean “an interpretation or conclusion about a patient’s needs, concerns, or health problems, and/or the decision to take action (or not), use or modify standard approaches, or improvise new ones as deemed appropriate by the patient’s response” (p. 204). Clinical judgment relies on knowing the patient in two ways—knowing the patient as a person and knowing the patient’s pattern of responses (Tanner, Benner, Chesla, & Gordon, 1993).

Tanner (2006) has proposed a model of clinical judgment, based on a synthesis of the clinical judgment literature, that can be used in complex, rapidly changing patient situations. The model includes:

-

Noticing—“A perceptual grasp of the situation at hand” (p. 208). Noticing, Tanner says, is “a function of nurses’ expectations of the situation, whether they are explicit or not” and further that “these expectations stem from nurses’ knowledge of the particular patient and his or her patterns of responses; their clinical or practical knowledge of similar patients, drawn from experience; and their textbook knowledge” (p. 208).

- Interpreting—“Developing a sufficient understanding of the situation to respond” (p. 208). Noticing triggers reasoning patterns that help nurses interpret the data and decide on a course of action.

- Responding—“Deciding on a course of action deemed appropriate for the situation, which may include ‘no immediate action’” (p. 208).

- Reflecting—“Attending to the patients’ responses to the nursing action while in the process of acting” (reflection in action) and “reviewing the outcomes of the action, focusing on the appropriateness of all of the preceding aspects (i.e., what was noticed, how it was interpreted, and how the nurse responded)” (p. 208; reflection on action).

The use of this model can be helpful to preceptors as a structure for debriefing. It is a model of expert practice—what the new graduate aims for and what the experienced nurse needs to perfect. Based on Tanner’s model, Lasater (2007) developed a detailed rubric (Lasater Clinical Judgment Rubric [LCJR]) that could be used in simulation with dimensions for each of the phases of the model:

-

Noticing—Focused observation, recognizing deviations from expected patterns, information seeking

- Interpreting—Prioritizing data, making sense of data

- Responding—Calm, confident manner; clear communication; well-planned intervention/ flexibility; being skillful

- Reflecting—Evaluation/self-analysis, commitment to improvement

While the LCJR has been primarily used in academic settings, Miraglia and Asselin (2015) suggest that it can be used as a framework to enhance clinical judgment skills of novice and experienced nurses.

New graduate registered nurses (NGRNs) have been shown to need major improvements in their clinical judgment skills. In reviewing 10 years of data using the Performance Based Development System (PBDS) for assessment, del Bueno (2005) found that only 35% of NGRNs met the entry requirements (safe level) for clinical judgment, regardless of their prelicensure educational preparation. They were unable to translate theory into practice. Accordingly, del Bueno posits that clinical practice with preceptors who ask questions (as opposed to giving answers) is the most critical intervention needed to improve the clinical judgment skills of new graduates.

Developing Situational Awareness, Expert Reasoning, and Intuition

Situational awareness, expert reasoning, and intuition are critical attributes to move from novice to expert nurse. If you’ve ever walked into a patient room and instantly become alert because you knew that something wasn’t right—even if you didn’t know what was wrong—you’ve used your situational awareness, expert reasoning, and intuition.

Situational awareness is the foundation of decision-making and performance. Put simply,

situational awareness is being aware of what is happening around you, understanding what that information means now, and anticipating what it will mean in the future (Endsley & Jones, 2012). Begun in the aviation industry, the formal definition of situational awareness is “the perception of the elements in the environment in a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future” (Endsley, 1995, p. 36). Endsley’s model of situational awareness has three incremental levels: perception of the elements in the environment (gathering data); comprehension of the current situation (interpreting information); and projection of what can happen in the future (anticipation of future states) (Endsley, 1995; Orique & Despins, 2018; Stubbings, Chaboyer, & McMurray, 2012).

The first level includes becoming aware of overt and subtle important cues that can be perceived through any or all of the senses. A nurse’s abilities, training, experience, and information-processing, as well as level of stress, workload, noise, and complexity, can all positively or negatively affect whether and how well the cues are perceived.

The next level is interpreting the significance of and discerning the relationships between the cues and synthesizing what may appear to less-skilled nurses as disjointed cues into the whole of the situation.

The last level in the model is predicting and anticipating what will happen next. Endsley and Jones (2012) note the importance of time in situational awareness—that is, anticipating how much time is available in which to act. Nurses with expert situational awareness can quickly identify that something is wrong, distill the important cues, put the pieces of information together, anticipate what will happen next and how quickly it will happen, and know what to do to intervene.

Malcolm Gladwell, in his book

Blink (2005), discusses the

adaptive unconscious of the mind, which he describes as “a kind of giant computer that quickly and quietly processes a lot of the data we need in order to keep functioning as human beings” (p. 11) and a “decision-making apparatus that’s capable of making very quick judgments based on very little information” (p. 12). The key themes of the research described in

Blink are:

- Decisions made very quickly can be every bit as good as decisions made cautiously and deliberately.

- We have to learn when we should trust our instincts and when we should be wary of them.

- Our snap judgments and first impressions can be educated and controlled.

Gladwell describes what he calls

thin-slicing, “the ability of our unconscious to find patterns in situations and behavior based on very narrow slices of experience” (p. 23). In this case, the term “experience” is not being used, for example, to mean the long-term experience of caring for many patients of the same type, but rather “very narrow slices of experience” would refer to when you first walk into a patient’s room and within seconds know that something does not fit the pattern you expect to see.

Gary Klein (1998) has studied nurses and other people who make decisions under time pressure when the stakes are high (e.g., firefighters, Navy SEALS, battlefield platoon leaders). Based on his research, he has found that what is generally termed “intuition” comes from experience, that we recognize things without knowing how we do the recognizing, and that what actually occurs is that we are drawn to certain cues because of situational awareness. He also notes, however, that because we often don’t understand that we actually have experience behind “intuition,” intuition gets discounted as hunches or guesses. His research, indeed, shows just the opposite. His findings indicate that the part of intuition that involves pattern matching and recognition of familiar and typical cases can be trained by expanding people’s experience base.

Klein (1998) describes what he has termed the recognition-primed decision model, a model that brings together two processes: “the way decision makers size up the situation to recognize which course of action makes sense, and the way they evaluate the course of action by imagining it” (p. 24).

Decision makers recognize the situation as typical and familiar . . . and proceed to take action. They understand what types of goals make sense (so priorities make sense), which cues are important (so there is not an overload of information), what to expect next (so they can prepare themselves and notice surprises, and the typical way of responding in a given situation. By recognizing a situation as typical, they also recognize a course of action likely to succeed (Klein, 1998, p. 24).

This is compared to a rational choice strategy, a step-by-step process of considering and eliminating alternatives, which is similar to what we do in the nursing process. Though a rational choice strategy is often needed as a first step for novices or for initially working in teams to determine how everyone views the options, it is less useful with experts, who usually look for the first workable option (based on their knowledge and experience) in the current situation, and for high-risk situations that require rapid response.

Klein (1998) notes many things that experts can see that are invisible to others (pp. 148–149):

-

Patterns that novices do not notice

- Anomalies, events that did not happen, and other violations of expectancies

- The big picture (situation awareness)

- The way things work

- Opportunities and improvisations

- Events that either already happened (the past) or are going to happen (the future)

- Differences that are too small for novices to notice

- Their own limitations

In describing expert nursing, Dreyfus and Dreyfus (2009) note that experts use deliberative rationality— that is, when time permits, they think before they act, but normally, “they do not think about their rules for choosing goals or their reasons for choosing possible actions” (p. 16). Deliberative rationality (the kind of detached, meditative reflection exhibited by the expert when time permits thought), they say, “stands at the intersection of theory and practice. It is detached, reasoned observation of one’s intuitive, practice-based behavior with an eye to challenging, and perhaps improving, intuition without replacing it by the purely theory-based action of the novice, advanced beginner, or competent performer” (pp. 17–18).

Debriefing after an incident in which situational awareness, expert reason, and intuition are used is important to learning. The preceptor needs to walk through the whole process step-by-step with the preceptee—discussing observations, rationale for actions, etc., and answering whatever questions the preceptee has. This may take some practice and reflection for the preceptor in order to be able to break down what was done intuitively so the preceptee can understand the steps and the logic.

Confidence

Self-efficacy (confidence) is the belief of individuals in their capability to exercise some measure of control over their own functioning and over environmental events (Bandura, 1997). According to Bandura, “A capability is only as good as its execution. The self-assurance with which people approach and manage difficult tasks determines whether they make good or poor use of their capabilities.

Insidious self-doubts can easily overrule the best of skills” (1997, p. 35) and “unless people believe they can produce desired results and forestall detrimental ones by their actions, they have little incentive to act or to persevere in the face of difficulties. Whatever other factors may operate as guides and motivators, they are rooted in the core belief that one has the power to produce effects by one’s actions” (Bandura, 2009, p. 179).

Kanter (2006) notes that confidence consists of positive expectations for favorable outcomes and influences an individual’s willingness to invest. “Confidence,” she says, “is a sweet spot between arrogance and despair. Arrogance involves the failure to see any flaws or weaknesses, despair the failure to acknowledge any strengths” (p. 8).

Manojlovich (2005), in a study of predictors of professional nursing practice behaviors in hospital settings, found a significant relationship between self-efficacy and professional behaviors. Ulrich et al. (2010) found that self-confidence improved in NGRNs across and beyond an 18-week immersion RN residency that used one-to-one preceptors.

Helping preceptees develop confidence in themselves requires the use of many of the preceptor roles described in Chapter 1 and requires the creation of a positive, enriching, and supportive learning environment. Competence and confidence are interrelated—each builds on, reinforces, and promotes the other.

Conclusion

Competence, critical thinking, clinical reasoning, clinical judgment, and confidence are all necessary components of any preceptorship. Role competence can be attained only by the connection of theory and practice. Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment are the keys to making that happen. Competence without confidence is opportunity wasted. Preceptors are charged with helping preceptees master critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment skills so preceptees can move from novice to expert competency.

Beth Tamplet Ulrich, EdD, RN, FACHE, FAAN, is a professor at the Cizik School of Nursing at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, USA, and editor of

Beth Tamplet Ulrich, EdD, RN, FACHE, FAAN, is a professor at the Cizik School of Nursing at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, USA, and editor of Nephrology Nursing Journal,

the professional journal of the American Nephrology Nurses Association.

To purchase Mastering Precepting: A Nurse's Handbook for Success (Second Edition).

References

Alfaro-LeFevre, R. (1999).

Critical thinking in nursing: A practical approach (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company.

Alfaro-LeFevre, R. (2017).

Critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment: A practical approach (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

American Nurses Association. (2010).

Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (2nd ed.). Silver Spring, MD: Author.

American Nurses Association. (2014).

Professional role competence (Position statement). Silver Spring, MD: Author. Retrieved from https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/official-position-statements/

American Nurses Association. (2015a).

Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. Silver Spring, MD: Author.

American Nurses Association. (2015b). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). Silver Spring, MD: Author.

American Philosophical Association. (1990).

Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. ERIC Doc No. ED 315 423.

Attri, R. K. (2017).

5 training guidelines: Skill acquisition towards unconscious competence. Retrieved from https://www. speedtoproficiency.com/blog/skill-acquisition-unconscious-competence/

Bandura, A. (1997).

Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

Bandura, A. (2009). Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In E. A. Locke (Ed.),

Handbook of principles of organization behavior (2nd ed., pp. 179–200). New York, NY: Wiley.

Berkow, S., Virkstis, K., Stewart, J., Aronson, S., & Donohue, M. (2011). Assessing individual frontline nurse critical thinking.

Journal of Nursing Administration, 41(4), 168–171. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3182118528

Cannon, H. M., Feinstein, A. H., & Friesen, D. P. (2010). Managing complexity: Applying the conscious-competence model to experiential learning.

Developments in Business Simulations and Experiential Learning, 37, 172–182.

Chan, Z. C. (2013). A systematic review of critical thinking in nursing education.

Nursing Education Today, 33, 236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.007

Chatfield, T. (2018).

Critical thinking: Your guide to effective argument, successful analysis, and independent study. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

del Bueno, D. J. (2005). Why can’t new registered nurse graduates think like nurses?

Nursing Education Perspectives, 26(5), 278–282.

Dreyfus, H. L., & Dreyfus, S. E. (2009). The relationship of theory and practice in the acquisition of skill. In P. Benner, C. Tanner, & C. Chesla (Eds.),

Expertise in nursing practice: Caring, clinical judgment, and ethics (2nd ed., pp. 1–24). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Endsley, M. R. (1995). Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems.

Human Factors, 37(1), 32–64.

Endsley, M. R., & Jones, D. G. (2012).

Designing for situation awareness: An approach to user-centered design (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Facione, N. C., & Facione, P. A. (1996). Externalizing the critical thinking in knowledge development and clinical judgment.

Nursing Outlook, 44(3), 129–136.

Facione, N. C., & Facione, P. A. (2008). Critical thinking and clinical judgment. In N. C. Facione & P. A. Facione (Eds.),

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning in the health sciences: A teaching anthology (pp. 1–13). Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press.

Facione, P. A. (1990).

Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press. Retrieved from http://www.insightassessment.com/CT-Resources/Expert-Consensus-on-Critical-Thinking

Facione, P. A. (2011).

Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Millbrae, CA: The California Academic Press. Retrieved from http://www.insightassessment.com/CT-Resources

Gladwell, M. (2005).

Blink: The power of thinking without thinking. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

Howell, W. S. (1982).

The empathetic communicator. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Jackson, M. (2006). Defining the concept of critical thinking. In M. Jackson, D. D. Ignatavicius, & B. Case (Eds.),

Conversations in critical thinking and clinical judgment (pp. 3–18). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Kanter, R. M. (2006).

Confidence: How winning streaks and losing streaks begin and end. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Kearney, M. H., & Kenward, K. (2010). Nurses’ competence development during the first 5 years of practice.

Journal of Nursing Regulation, 1(1), 9–15.

Klein, G. (1998).

Sources of power: How people make decisions. Boston, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Lasater, K. (2007). Clinical judgment development: Using simulation to create an assessment rubric.

Journal of Nursing Education, 46(11), 496–503.

Lenburg, C. (1999). The framework, concepts and methods of the Competency Outcomes and Performances Assessment (COPA) model.

The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 4(2), Manuscript 2.

Manojlovich, M. (2005). Predictors of professional nursing practice behaviors in hospital settings.

Nursing Research, 54(1), 41–47.

Miraglia, R., & Asselin, M. E. (2015). The Lasater Clinical Judgment Rubric as a framework to enhance clinical judgment in novice and experienced nurses.

Journal for Nurses in Professional Development, 31(5), 284–291. doi: 10.1097/ NND.0000000000000209

Orique, S. B., & Despins, L. (2018). Evaluating situation awareness: An integrative review.

Western Journal of Nursing Research, 40(3), 388–424. doi: 10.1177/0193945917697230

Paul, R. W., & Heaslip, P. (1995). Critical thinking and intuitive nursing practice.

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 22(1), 40–47.

Scheffer, B. K., & Rubenfeld, M. G. (2000). A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing.

Journal of Nursing Education, 39(8), 352–359.

Simmons, B., Lanuza, D., Fonteyn, M., Hicks, F., & Holm, K. (2003). Clinical reasoning in experienced nurses.

Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25(6), 701–719.

Stubbings, L., Chaboyer, W., & McMurray, A. (2012). Nurses’ use of situation awareness in decision-making: An integrative review.

Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(7), 1443–1453.

Tanner, C. A. (2006). Thinking like a nurse: A research-based model of clinical judgment in nursing.

Journal of Nursing Education, 45(6), 204–211.

Tanner, C. A., Benner, P., Chesla, C., & Gordon, D. R. (1993). The phenomenology of knowing the patient.

Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 25(4), 273–280.

Ulrich, B., Krozek, C., Early, S., Ashlock, C. H., Africa, L. M., & Carman, M. L. (2010). Improving retention, confidence, and competence of new graduate nurses: Results from a 10-year longitudinal database.

Nursing Economic$, 28(6), 363–376.

Victor-Chmil, J. (2013). Critical thinking versus clinical reasoning versus clinical judgment.

Nurse Educator, 38(1), 34–36.

Wright, D. (2005).

The ultimate guide to competency assessment in health care (3rd ed.). Minneapolis, MN: Author.

Wright, D. (2015).

Competency assessment field guide: A real world guide for implementation and application. Minneapolis, MN: Author.