This chapter from A Nurse's Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Dissertation or Scholarly Project, Second Edition, discusses the elements of your introduction—from background information to your action plan.

ELEMENTS OF YOUR INTRODUCTION

- Provides some background information so that readers understand the issue

- Explains why the issue is important

- Describes what is known about the issue

- States what we need to find out or what action needs to be taken and why

- Presents how you plan to do that (your study/project)

There’s a good reason you chose your dissertation or scholarly project topic. Maybe an experience in your personal life left you determined to make things better for others experiencing the same thing. Or perhaps you’ve witnessed too many patients having poor outcomes after a certain procedure and you want to figure out a way to change that. Maybe you chose your topic in response to a lack of knowledge or poor attitudes about a particular condition that causes unnecessary suffering for those who experience it. Or perhaps you’ve noticed a systems issue that is creating increased work stress for fellow nurses.

There’s a good reason you chose your dissertation or scholarly project topic. Maybe an experience in your personal life left you determined to make things better for others experiencing the same thing. Or perhaps you’ve witnessed too many patients having poor outcomes after a certain procedure and you want to figure out a way to change that. Maybe you chose your topic in response to a lack of knowledge or poor attitudes about a particular condition that causes unnecessary suffering for those who experience it. Or perhaps you’ve noticed a systems issue that is creating increased work stress for fellow nurses.

Whatever it is, something made you sit up and pay attention. The introduction is your opportunity to make the reader do the same. In this part of the dissertation, you tell readers why you care about this topic, and even more important, why they should care, too.

In dissertation/project speak, we call this establishing significance. In plain English, we’re saying, “Hey, listen up! This is important, and here’s why.”

Of course, you can’t expect readers to just take your word for it. You need to first give them information so that they understand the problem, and you need to back up that information with evidence. After you do that, you can ask them to consider your idea for what we need to do next, whether that is gathering more information or trying out a solution.

You’ve already started

Good news: You’ve already done most of the work for this chapter! Much of the introduction will come from all the information you gathered when you did your literature review. What you want to do is summarize the literature review. As you do so, include enough information to familiarize readers with your topic and to convince them of its importance without extensive details or an in-depth review of individual studies.

Creating an outline

You can begin by developing an outline based on the required elements. To do so, first answer each of the following questions (which correlate with required elements 1 through 4 listed at the beginning of this chapter) with one or two sentences:

- What is happening?

- Why should we care?

- What do we know now?

- What do we need to find out and why? or What do we need to do to address this?

If you have a hard time keeping your answers to one or two sentences, you might need to refine your study/project to focus it more. Get rid of any noise—all that extraneous information that is not really bringing value to the paper. It’s the old need to know vs. nice to know. In a dissertation/project, we only want the need to know stuff. If information doesn’t add value to the paper, it detracts from it and may even confuse the reader. So be sure to stay focused, like a photographer focusing in on the intended subject and letting everything else blur out so that the viewer’s eyes go right to what’s important.

After you’ve answered the questions, read your answers in order. Each answer should connect with what comes before, and all of them should lead you straight to a logical therefore statement.

Therefore, I am going to conduct a study to…

Therefore, I designed a quality improvement project to…

If the answers don’t lead directly to the therefore statement, what’s missing? Where does the connection get lost? If you haven’t gotten the reader to care, then it doesn’t matter what you know and what you want to do. Or maybe now the reader cares but wonders why you need to do this particular study at this particular time, because it doesn’t seem to be the next logical thing to do based on what’s already been done. Or you haven’t shown how the solution you propose could effectively address the problem you’ve identified.

Here’s an example of what the answers to these questions might be for a dissertation proposal on intimate partner violence (IPV) in the rural setting:

- What is happening?

IPV is a pervasive health and social problem in the United States. One out of three women experience IPV in their lifetime.

- Why should we care?

IPV causes tremendous physical and emotional suffering and even death. It’s costly to individual women and society.

- What do we know now?

Women in the rural setting who experience IPV face unique challenges. Current support and resources are inadequate and ineffective.

- What do we need to find out and why?

There is little research on the lived experience of IPV for women in the rural setting. We need to understand this so we can develop effective services and provide appropriate resources and support.

Therefore, I propose a qualitative descriptive study of the lived experience of women who experience intimate partner violence in the rural setting.

Here’s an example for a scholarly project to decrease the rate of central line-associated bloodstream infections in an ICU:

- What is happening?

Rates of central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) in the intensive care unit are higher than national benchmarks.

- Why should we care?

CLABSI is associated with higher morbidity rates and a mortality rate of 10% to 20%. It leads to an increased length of stay for the patient and costs the hospital over $28,000 per patient. CLABSI costs the U.S. healthcare system close to 2 billion dollars annually.

- What do we know now?

CLABSIs are preventable. Evidence-based protocols reduce the rate of CLABSIs. The Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) toolkit has reduced the national rate of CLABSIs by 41%.

- What do we need to do to address this?

Follow evidence-based protocols in caring for patients with central lines.

Therefore, I am going to lead a team to modify the CUSP toolkit to meet the needs of the ICU and implement it on the unit.

After you’ve answered the questions satisfactorily, have someone unfamiliar with the topic review it. Does that person agree that the therefore statement makes perfect sense? If not, it’s back to the drawing board. If they do, brava!—you’re on your way.

After you’ve answered the questions satisfactorily, have someone unfamiliar with the topic review it. Does that person agree that the therefore statement makes perfect sense? If not, it’s back to the drawing board. If they do, brava!—you’re on your way.

How you proceed at this point depends on your own writing work style. Some people prefer to work from a detailed outline. If you do, you can now begin to fill in your answers with more particulars. If you are not an outline type of worker, you can move on to writing the introduction, as described later in this chapter.

Filling in the outline

Under each question, list the different pieces of information that you need to add. Depending on your topic and purpose, your outline should include some or all of the following information:

- What is happening?

- Condition, problem, issue

- Definition or brief description

- Population affected

- Epidemiology

- How many

- How often

- Where (e.g., United States, globally, developing countries, hospital or community)

- Mortality rates

- Local problem (for quality improvement project)

- Associated concepts necessary to understanding of problem or approach

- Why should we care?

- Morbidity and mortality

- Pain and suffering it causes

- Economic costs

- Individual

- Organization/institution

- Society

- Increasing or worsening?

- Consequences/impact of local problem

- What do we know now?

- Recent research

- Current treatments or interventions

- Outcomes

- Limitations

- What do we need to find out and why?

- Questions that still need to be answered

- Interventions to be trialed

- Factors or outcomes in a specific population

- Benefits to be gained

- Better patient outcomes

- More effective interventions

- Improved services

- Workforce issues

- Improved systems

Writing the introduction

When you start writing this part of your dissertation, remember that each section is an introduction to the material included. So, don’t get too detailed. The important thing is that you adequately and succinctly cover all these areas. In your Literature Review (Chapter Two), you critically review prior research and cover the individual studies in depth. In the Introduction, in contrast, you present what is known with appropriate citations of the evidence but don’t get into detailed information about that evidence.

In addition, you’ll notice some overlap among the four questions. Don’t try to adhere to a structure that rigidly partitions answers to each question. For example, when you talk about prevalence in answer to the “What is happening?” question, you are beginning to make a case for significance.

What is happening?

The first paragraph introduces your topic and makes a brief statement about its significance. Within the first two sentences, the reader should know what the topic is. Don’t take the reader on a roundabout trip to your topic. If your topic is stress incontinence in older women, start with a statement about stress incontinence. Don’t start by talking about the aging of the population and then explain how older people have more problems with incontinence and that there are different types of incontinence, one of which is stress incontinence. Try to get the topic in the first sentence. After we know you’re talking about stress incontinence, you can go on to tell us that it is more common in older women and that its prevalence is increasing with the aging of the population.

Describe the population that is affected and provide statistics on the prevalence:

- How many people are affected, or how often does it happen?

- How big is this problem?

- What population is primarily affected?

- What are the mortality and morbidity rates?

- Is the problem increasing, or is its impact becoming greater?

Most of the time, you should write from the general to the specific. So, your first paragraph will state the problem and its prevalence and make a general statement about its impact. Then succeeding paragraphs will provide more details that add to the reader’s understanding of the topic, its significance, and related concepts. In some cases, though, you may want to start a paragraph or section by first stating the specific topic and then pull back to provide context, as in the previous example of a study on stress incontinence in older women.

Most of the time, you should write from the general to the specific. So, your first paragraph will state the problem and its prevalence and make a general statement about its impact. Then succeeding paragraphs will provide more details that add to the reader’s understanding of the topic, its significance, and related concepts. In some cases, though, you may want to start a paragraph or section by first stating the specific topic and then pull back to provide context, as in the previous example of a study on stress incontinence in older women.

In a scholarly project, you also have to give the reader background information on the “local problem.” What is happening in your specific setting that compels you to do this quality improvement project? How do you know there is a problem? What is the population affected? What are the consequences of the problem?

Why should we care?

Now that readers know what you’re going to be talking about, you need to convince them of its importance. You do this by talking about its impact on those affected by it and on society. If you haven’t talked about prevalence, an important aspect of a problem’s significance, you’ll want to discuss it here.

The impact on those it affects is the other important aspect of a problem’s significance. Depending on your topic, this may include any of the following:

- Physical and mental health effects

- Social implications

- Economic impact on the individual and society

- Contribution to healthcare costs

- Healthcare system implications

- Patient safety outcomes

- Impact on the nursing profession

Be careful how and where you talk about the economic costs of a problem. You don’t want it to appear that you are prioritizing cost over people. If your purpose is related to a health systems problem, economic costs may be a primary factor. However, if it is related to a patient outcomes problem, cost may be one of the reasons we should care, but it should not be the primary one. You can make this clear in the wording and where in the text you place information. If it is a patient-related problem, talk about cost last and begin with a transitional phrase such as in addition to or along with [the impact on patients]:

In addition to the decrease in patient suffering and lower risk of death, improving our CLABSI rates will result in significant cost savings to the hospital.

What do we know now?

You will have included some of what we know now in answering the first two questions. In answering this question, though, you want to talk about what is known in relation to the specific purpose of your study or project. This will then lead the reader to what we need to find out, which is the knowledge or practice gap that your dissertation or project is trying to fill.

If your study or project is looking to better understand a problem or discover more information about the impact of a problem, then in this section you’ll describe current understanding or information. If you are doing an interventional study or quality improvement project that looks at how to address a problem, you also need to describe what we currently know about what works or doesn’t work (in other words, what’s already been tried and how it worked out).

What do we need to find out and why?

Now that you’ve established where we’re at currently, it’s time to let the reader know what the next step should be. This is where you introduce the knowledge or practice gap that you are going to address in your study or project. This will be a shorter version of what you discuss in the literature review, but the same format applies. Use a transitional sentence to move from what is known to what we need to find out or from what is known about a problem to what you are proposing to do about the problem. Then tell the reader why the knowledge or project is necessary.

But remember, keep it brief. One or two sentences should cover it. For example:

Though there is evidence from studies of disenfranchised grief to suggest that parents who experience the death of an estranged son or daughter may suffer complicated grief and receive less support than other bereaved parents, there is little research that explores this experience in this population. Understanding the lived experience of grief after the death of an estranged son or daughter is needed for us to develop effective counseling and support services for these parents.

And finally, what you are going to do:

Therefore, I am going to conduct a qualitative phenomenological study of the meaning of grief in parents following the death of an estranged son or daughter.

If you’ve done your job well, the therefore statement is inevitable. The reader is already there thinking, well, of course now you have to do that! Everything that came before has led directly to it.

Purpose statements

Your therefore statement may be worded as a purpose statement (the therefore is implied). Either way, make sure to state it clearly and concisely.

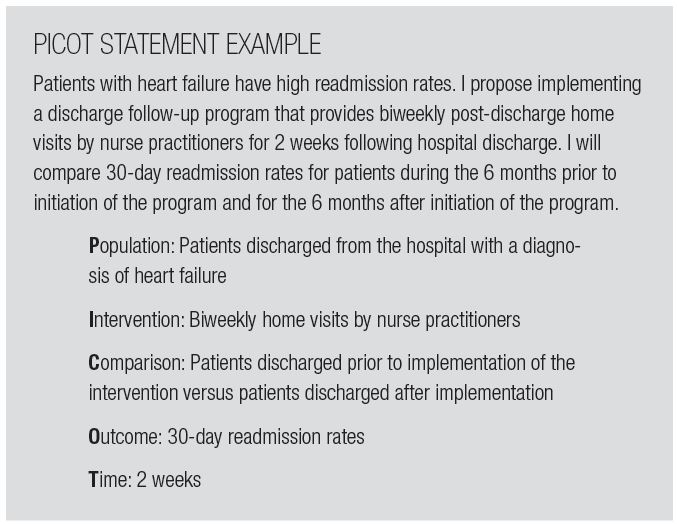

PICOT statements

You may be directed to write a PICOT problem statement, particularly if you are doing quantitative research or a quality improvement project. Here’s what a PICOT statement covers:

Population: Who is the focus of your study or project?

Intervention: What activity/behavior is being tested?

Comparison: What group are you comparing your population to?

Outcome: What are the outcomes you are examining?

Time: What is the duration of the intervention or study period?

Not all purpose statements or research questions can be formulated into a PICOT problem statement. If you are doing a qualitative study, you might not have an intervention, comparison, outcome, or time.

Not all purpose statements or research questions can be formulated into a PICOT problem statement. If you are doing a qualitative study, you might not have an intervention, comparison, outcome, or time.

Your plan (methodology)

After you state your purpose, you need to briefly describe how you propose to accomplish it. If you are doing a research study, your purpose statement usually includes the methodological approach you plan to use (as shown in the preceding examples). You should then describe your design in one or two sentences. Are you going to use a survey? Conduct interviews? Do focus groups? What is the sampling frame? What’s the duration of the project or study period? For example:

Therefore, I propose a discharge follow-up program for heart failure patients that provides biweekly home visits by nurse practitioners for 2 weeks following hospital discharge. I will compare 30-day readmission rates for patients during the 6 months prior to initiation of the program and for the 6 months after initiation of the program.

Research questions

Finally, you include your specific research question or questions. This is usually your purpose statement reformulated as a question but may also include additional questions that drill down into more specifics:

What is the lived experience of IPV for women in the context of the rural setting?

What are the IPV-related knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of healthcare providers in the rural setting?

Will biweekly home visits conducted by nurse practitioners for 2 weeks post hospital discharge reduce readmission rates for heart failure patients?

Does participation in simulation teamwork exercises improve the perception of teamwork among interprofessional operating room staff?

If you have specific hypotheses, you include those in this section as well.

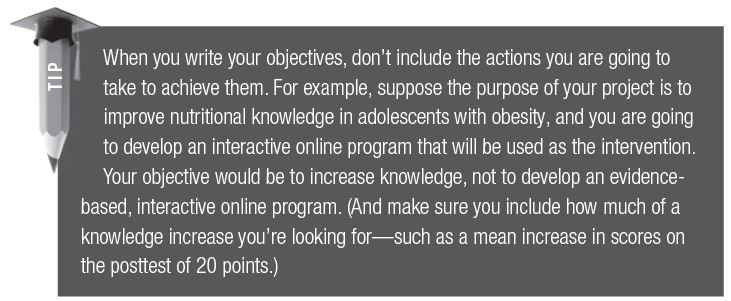

For a scholarly project, you’ll need to include measurable objectives also. How much improvement are you looking for? Your measurement may be a certain percentage change in a rate or a benchmark to be reached. For example, in the previous heart failure project, the objective might read: In the 6 months following the establishment of nurse practitioner post-discharge home visits, the average 30-day HF readmission rate will be no greater than 18%.

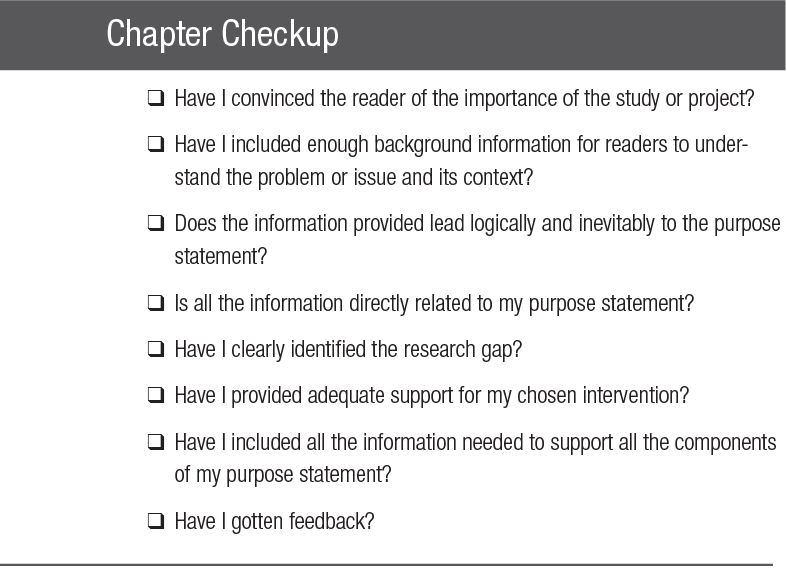

Checking that you’ve covered your purpose statement

When you finish the introduction, go back and check that you’ve covered all aspects of your purpose or therefore statement. Break the purpose statement into questions and check that each question is answered, albeit briefly, in the introduction. Not knowing the answer to any of the questions reveals gaps in your thinking or in your review of the literature.

Nothing about your purpose statement should be arbitrary. You should be able to clearly see where it came from: What in the literature or your practice supports your decisions about variables, time duration, and outcome measures?

So, let’s look at the example of the discharge follow-up program for heart failure patients:

Therefore, I propose a discharge follow-up program that provides biweekly home visits by nurse practitioners for 2 weeks following hospital discharge. I will compare 30-day readmission rates for patients during the 6 months prior to initiation of the program and for the 6 months after initiation of the program.

For this purpose statement, you would want to be able to answer the following questions:

- Why look at a discharge follow-up program for HF patients?

- Why post-discharge home visits as the follow-up intervention?

- Why make the visits biweekly?

- Why by nurse practitioners (versus other healthcare personnel)?

- Why 2 weeks duration following hospital discharge?

- Why 30-day readmission rates as the outcome measure?

Of course, you will only be able to answer all the questions if your literature review was comprehensive and complete. If you haven’t answered all these questions in the introduction, go back to your literature review and see whether the answers are there. If not, you’ve got to get back into the literature and find them and revise your literature review to include that information before moving on.

If you can answer all the questions, then onward to Chapter 2, “Writing Your Literature Review”!

Karen Roush is an assistant professor of nursing at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and a former editorial director and clinical managing editor for the American Journal of Nursing (AJN).