Imogene M. King, pioneer nursing theorist and international nursing scholar, died 24 December 2007.

Imogene M. King, 84, pioneer nursing theorist and international nursing scholar, died Dec. 24, 2007, in South Pasadena, Florida, USA. She earned recognition as a nurse theorist through publication of

Toward a Theory for Nursing: General Concepts of Human Behavior in 1971 and

A Theory for Nursing: Systems, Concepts, Process in 1981, as well as numerous articles related to her conceptual system and theory of goal attainment. She was one of the first nurse theorists to link academic theory with clinical nursing practice.

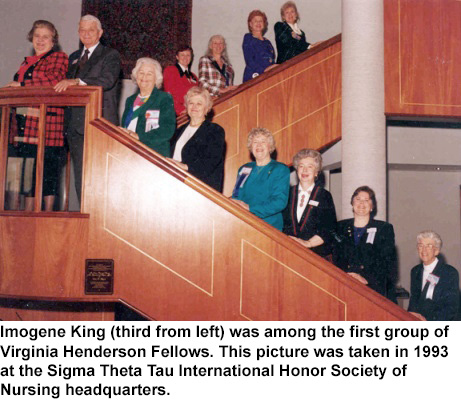

An esteemed member of the Honor Society of Nursing, Sigma Theta Tau International, King received the honor society’s 1989 Elizabeth Russell Founders Award for Education and, in 1993, was a member of the inaugural group of Virginia Henderson Fellows. She also served as president of Delta Beta Chapter, distinguished lecturer, and co-chair of the 1991 Sigma Theta Tau International Biennial Convention held in Tampa, Florida. King and Jacqueline Fawcett, co-editors of

The Language of Nursing Theory and Metatheory (1997), generously donated royalties from the book to the Sigma Theta Tau International Research Endowment.

"As a recognized global leader, Imogene King truly made a positive difference for the nursing profession," said Patricia E. Thompson, RN, EdD, FAAN, chief executive officer of the honor society. "She had a significant impact on nursing's scientific base."

She never planned to be a nurse

King was born Jan. 30, 1923, in West Point, Iowa. During her early high school years, she decided to pursue a career in teaching. However, her uncle, the town surgeon, offered to pay her tuition to nursing school. She eventually accepted, seeing nursing school as a way to escape life in a small town. Thus began her remarkable career in nursing.

King excelled in her nursing studies. She received a diploma in nursing from St. John’s Hospital School of Nursing in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1945; a Bachelor of Science in Nursing Education from St. Louis University in 1948; and a Master of Science in Nursing from St. Louis University in 1957. In 1961, she received a Doctorate in Education from Teachers College, Columbia University, where she studied under Mildred Montag.

Linking theory and practice

From 1945-51, King worked as a clinical instructor in medical-surgical nursing at St. John’s Hospital School of Nursing, where she was involved in efforts to change the curriculum from a medical model to a nursing model. From 1952-58, she was an instructor and assistant director of nursing at St. John’s.

After receiving her doctorate in 1961, King began work as an assistant professor at Loyola University Chicago. From 1966-68, she served as assistant chief in the Research Grants Branch, Division of Nursing, Bureau of Health Manpower and Welfare. In 1968, she was appointed professor and director of the School of Nursing at Ohio State University and in 1972, she returned to Loyola University as a professor in the graduate nursing program. In 1980, she accepted a position as professor at the University of South Florida College of Nursing. When she retired in 1990, King was honored as a professor emeritus.

In 1969, King conducted a World Health Organization nursing research seminar in Manila, Philippines, where she met Midori Sugimori of Japan. Over the years, the two nurses remained in touch. Sugimori translated King’s two theory books into Japanese, and the books strongly influenced nursing education in Japan. The doctoral dissertation of Tomomi Kameoka tested the theory of goal attainment in Japan. King was present when Kameoka presented her research at the honor society’s 2001 Biennial Convention.

King treasured her relationship with Sugimori, Kameoka and other Japanese nurses. “We have become friends as well as colleagues,” King wrote in a 1998 letter to the editor of

Reflections magazine [now

Reflections on Nursing Leadership]. With King’s support and encouragement, five Japanese nurses— Sugimori, Kameoka, Kumiko Hongo, Wakako Sahahiro and Naomi Funashima—were inducted in 1998 into Delta Beta Chapter at the University of South Florida.

She never really retired

After she retired from teaching, King traveled throughout the United States, Canada, Japan, Germany and Sweden, consulting with nurses, mentoring students, presenting at conferences and attending book signings. She often advised students, faculty and colleagues who were implementing her theory.

King received awards from many organizations in honor of her contributions to the nursing profession. In 2005, she was named a “Living Legend” by the American Academy of Nursing. She was inducted into halls of fame of the Florida Nurses Association, American Nurses Association and Teachers College of Columbia University. In 1997, she received a gold medallion from the governor of Florida for advancing the nursing profession in that state. In 1996, she received the American Nurses Association’s Jessie Scott Award, which is presented to a registered nurse whose accomplishments in practice, education or research demonstrate the interdependence of those fields and their significance in improving nursing and health care. In 1989, she received an honorary doctorate from Loyola University, where her nursing archives are housed.

Despite King’s many awards and honors, she considered teaching students to be her most important accomplishment. Over the years, she enjoyed watching her nursing students become expert practitioners, teachers and researchers. “That is the biggest honor of all,” King said. (Houser & Player, 2007, p. 130)

Honoring her memory

On Dec. 24, Patricia Quigley, PhD, ARNP, CRRN, FAAN, announced King’s passing to nursing colleagues with these words: “May we all burn a candle today for the light that Imogene shined on us with her smile, laughter, knowledge and passion for each day. We all shared in our love for her. Combining religion and science through nursing, her inspired voice was never weak—but strong with passion and conviction.”

Four of the Japanese nurses whom King had mentored—Midori Sugimori, Naomi Funashima, Kyoko Yokoyama and Tomomi Kameoka—traveled to Florida to pay their respects upon hearing of King’s death.

Friends, relatives and colleagues attended memorial services held Jan. 4 in St. Pete Beach, Florida, and Jan. 19 in Fort Madison, Iowa, where she was buried. During both services, Messmer read the Nightingale Tribute, which included a synopsis of King’s career and a poem, “Imogene Was There.” Seven green Irish roses symbolized the seven decades of her nursing career. A Nightingale Lamp from the University of Pittsburgh, her graduation picture from St. John’s Hospital School of Nursing and a current photo were also displayed for the memorial services.

Kammie Monarch, RN, MSN, JD, chief operating officer of the honor society, expressed appreciation for the support and care that Messmer gave to King. “More of us need to be that attentive to nursing’s leaders,” Monarch says.

References and resources:

Houser, B.P., & Player, K.N. (2007).

Pivotal Moments in Nursing, Volume II. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

King, I.M., & Fawcett, J. (1997).

The Language of Nursing Theory and Metatheory. Indianapolis, IN: Center Nursing Publishing.

Messmer, P. (2000). Imogene King 1923-, in V.L. Bullough & L. Sentz (Eds.),

American Nursing: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 3 (pp. 164-167). New York: Springer.