This chapter from B Is for Balance, Second Edition, examines the impact of fatigue on work, safety, well-being, and stress.

“The body says what words cannot."

–Martha Graham

Clear thinking, critical thinking, and clear communication are imperatives in all employees and in all professions. We are challenged more than ever before with the effect of fatigue on outcomes. Fatigue is a reality in nursing. Every day, during every shift, nurses can experience fatigue of their minds, bodies, and spirits. Workload, work hours, work structures, and many other factors can indirectly or directly cause fatigue in multiple industries and affect safety. Regardless of the profession, fatigue takes its toll and has affected physicians, nurses, police, firefighters, emergency personnel, fighter pilots, naval crews, and transportation workers—all of whom work in environments where the timing of work is not always conveniently matched to the human circadian rhythm, and the length of the work may challenge one’s ability to function safely (Dorrian, Lamond, & Dawson, 2000).

Clear thinking, critical thinking, and clear communication are imperatives in all employees and in all professions. We are challenged more than ever before with the effect of fatigue on outcomes. Fatigue is a reality in nursing. Every day, during every shift, nurses can experience fatigue of their minds, bodies, and spirits. Workload, work hours, work structures, and many other factors can indirectly or directly cause fatigue in multiple industries and affect safety. Regardless of the profession, fatigue takes its toll and has affected physicians, nurses, police, firefighters, emergency personnel, fighter pilots, naval crews, and transportation workers—all of whom work in environments where the timing of work is not always conveniently matched to the human circadian rhythm, and the length of the work may challenge one’s ability to function safely (Dorrian, Lamond, & Dawson, 2000).

Within the healthcare setting one of today’s greatest challenges is delivering safer care in complex, fast-moving environments. We recognize that in such environments things often can, and do, go wrong. Adverse events occur, and unintentional but serious harm comes to patients during routine clinical practice or as a result of a clinical decision.

Fatigue defined

Fatigue is mental or physical exhaustion that stops a person from being able to function normally. However, fatigue is more than just feeling tired or drowsy. You may often become tired through physical or mental effort; that is not unusual. When you are so weary that you cannot go on, that is true fatigue.

Fatigue is a factor that has been linked to stress, safety, and performance decrements in numerous work environments (Leung, Chan, Ng, & Wong, 2006).

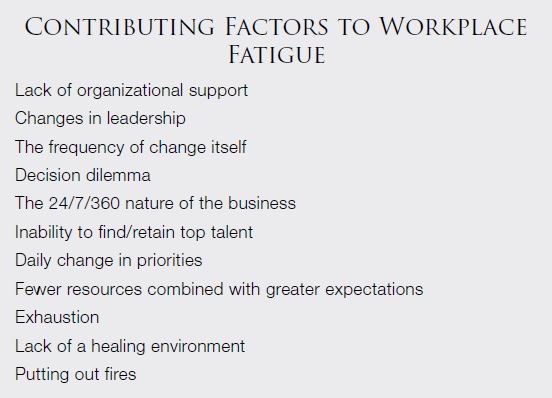

Fatigue can be physical or psychological—or a combination of the two—and can lead to compromised decision-making, reaction time, and critical thinking; it can also negatively influence general health (Drake, Luna, George, & Steege, 2012). Within the healthcare sector, where the commodity with which we deal is human lives and human happiness, there is great concern about fatigue. In December 2011, The Joint Commission (TJC) issued a Sentinel Event Alert, “Health Care Worker Fatigue and Patient Safety,” which identified that shift length and work schedules were found to have a significant impact on healthcare workers’ quantity and quality of sleep (TJC, 2011).

How does it feel?

The effects of fatigue increase with age. Those older than 50 years of age tend to have lighter, fragmented sleep, which can prevent them from receiving the recuperative effects from a full night of sleep and can make them more likely to become fatigued. Lack of sleep has been indirectly linked with mental and physical disorders, as well as what we refer to as “total fatigue.”

Mental fatigue

Anxiety and depression can be triggered or made worse by fatigue and irregular sleep patterns. Neurobehavioral effects include behavioral lapses (error of omission), false responses (error of commission), learning, and recall deficits. Mental fatigue levels may be influenced by mental and emotional demands in the workplace. The Mayo Clinic staff (2014) identifies psychological conditions such as anxiety, depression, grief, and stress as factors in mental fatigue.

Physical fatigue

We may be physically drained, and we do not know why. Could it be the work schedule or the work setting in which we operate? Could it be due to the challenges we face at home and perhaps the fact that each of our days has more than 24 hours? According to Barker and Nussbaum (2011), fatigue-induced sleep and rest habits may contribute to:

- Coronary heart disease (blocked arteries in the heart

- Ischemic heart disease (blocked arteries leading to lack of oxygen to the heart muscle

- High blood pressure

- Myocardial infarction (heart attack)

Our sensitive digestive tracts are designed to consume and absorb food at regular intervals. Shiftwork, not taking time for meals, and lack of hydration are known to contribute to:

- Bowel habit changes

- Digestive complaints

- Increased risk of peptic (stomach) ulcers

Fatigue and irregular sleep patterns have been associated with a number of negative effects for pregnant women and fertility rates, including:

- Increased risk of miscarriage

- Low birth-weight babies

- A higher occurrence of premature births

Adrenal fatigue

Adrenal fatigue is a collection of signs and symptoms, often known as a “syndrome” that occurs when the adrenal glands function below the necessary level. The greatest contributor to this common health challenge is stress, and stress is often associated with fatigue! “Fatigue” is a part of the label, and although you might not exhibit obvious signs of an illness, you live and function while feeling unwell. Does your day begin with coffee or carbonated beverages/energy drinks because you need a lift of some kind?

Adrenal fatigue has had many names, including non-Addison’s hypoadrenia, adrenal neurasthenia, and adrenal apathy. Although conventional (Western) medicine does not recognize it, millions of people are affected by it. Remember that the world of healthcare relies on “coding,” and if there is no code associated with a syndrome, it is not billable; thus, it does not exist. Try telling that to those who face this challenge each and every day.

Adrenal fatigue can wreak havoc with your life. In more serious cases, the activity of the adrenal glands is so diminished that you may have difficulty getting out of bed for more than a few hours per day. Other organs and systems can become affected. Changes occur in your carbohydrate, protein, and fat metabolism; fluid and electrolyte balance; heart and cardiovascular system; and even libido. Although your body does its best to compensate, it does not always succeed. The adrenal glands retaliate by mobilizing your body’s stress responders through hormones that regulate energy production and storage, immune function, heart rate, muscle tone, and other processes that enable you to cope with the stress (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2014). The result is that you are wiped out!

Total fatigue

Those who are fatigued exhibit lack of energy, apathy, inattention, difficulty concentrating, poor decision-making, lack of initiative, indifference, irritability, ptosis (eye irritation), slow reaction time, and poor communication. Physiologic effects of fatigue include insulin resistance, poor arousal response, and hypoxemia. Total fatigue refers to a state comprised of both dimensions: mental and physical. Over time, this may contribute to an inability to function at normal capacity and can lead to an increased risk of injury or error (WebMD, 2013).

"How many inner resources one needs to tolerate

a life of leisure without fatigue."

–Natalie Clifford Barney

Who owns fatigue?

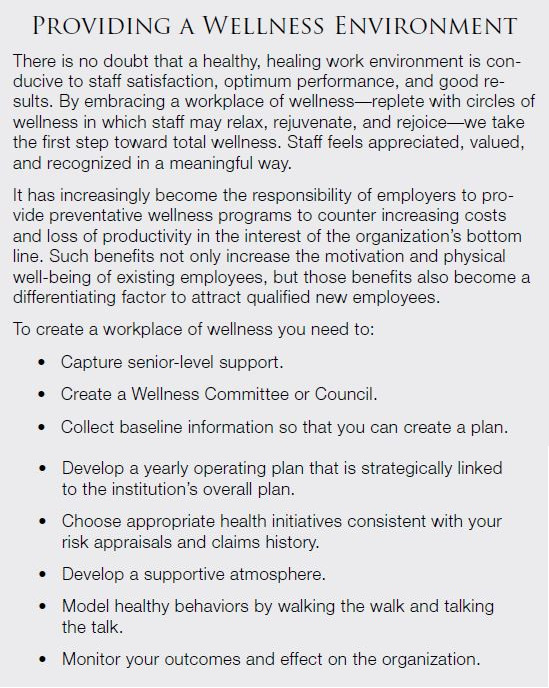

Registered nurses and employers share the responsibility of implementing strategies to reduce risks from shiftwork and long work hours. Stakeholders who have a contractual relationship with the worksite and influence work hours also have a responsibility to promote safe and healthy work hours. An optimal work environment proactively addresses fatigue and promotes wellness. The American Nurses Association (ANA, 2014a) supports the health and well-being of the nurse and promotes strategies to reduce the risks of working while fatigued.

Employer responsibility

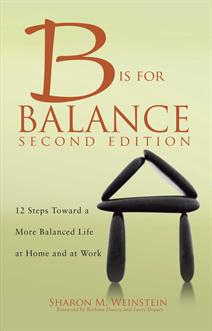

The employer can do much to shift the paradigm and create a culture of safety, wellness, and caring. Clear and compelling visions start us along a path of generating a future we deserve to have. In the healthcare setting, everyone assumes responsibility for patient safety and good outcomes. Nurses might argue that they own safety, but it is clear that certain factors can and do contribute to fatigue on the part of employers/management (Hendren, 2011; Lerman et al., 2012; Reed, 2013). Even the best designed fatigue-management plans cannot regulate sleep behaviors during one’s rest periods and days off.

Any approach to addressing workplace fatigue must include collaboration among management and staff. In the healthcare setting, an assessment of current staffing, scheduling, and acuity levels is needed to avoid unsafe circumstances. Self-scheduling is perceived as an advantage on the part of nurses; however, the nurse who chooses to work 72 hours in a workweek is following the path to fatigue. Autonomy might win, but the human body fails. Recommendations for identifying and addressing fatigue-related risks include the following:

- Assess your fatigue-related risks—staffing, consecutive shifts, off-shift hours.

- Develop a plan to include education, strategies, and role modeling.

- Invite staff input in designing work schedules.

- Create and implement an alertness management plan.

- Provide nonpunitive opportunities for staff to express concerns about fatigue.

- Encourage teamwork to support staff who work long hours.

- Develop an internal system to monitor and report fatigue levels.

Promoting a positive, safe, work environment reduces the risk for job stress and the associated difficulties with not getting enough sleep. Safe levels of staffing are essential to providing a safer environment for all workers, especially those with responsibility for patient care. With fair compensation, staff will be less compelled to seek supplemental income through overtime, extra shifts, and other practices that are known to contribute to worker fatigue.

Employee responsibility

Any employee is responsible for practicing healthy behaviors that reduce the risk for working while fatigued or sleepy, result in arriving to work alert and well rested, and promote a safe commute to and from work. This is true regardless of the industry in which one works! This responsibility might require that you reject a work assignment that compromises the availability of sufficient time for sleep and recovery from work—for example, when your shift ends at midnight, and you are expected to return to work, fully rested, by 7:00 a.m. We all have different recovery times. Our bodies and minds are unique, and this concept often involves scheduled shifts and mandatory or voluntary overtime. It is everyone’s responsibility to address one’s own, as well as coworker, fatigue. Employees must be responsible and know their limits.

"I’m a workaholic, so I ignore the signs of fatigue and just keep going and going, and then conk out when I get home. It can be pretty stressful."

–Keke Palmer

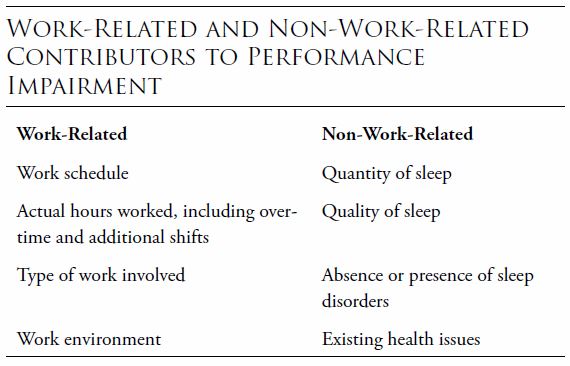

System responsibility

The outcome is only as good as the system. And the system has been created to ensure positive outcomes.

What should a leader do? The leader should find and fix problems, make safety a core value, partner with others to make minimizing fatigue a priority, and measure the results, making adjustments as needed.

Fatigue and performance

We want to do the best job possible. We want to perform at the highest level. We want to succeed. Sometimes the environment itself impairs our ability to do so. When I worked in Eastern Europe, my nurse colleagues did not have healthy work environments. At the time, they worked without electricity, without an emergency generator, without adequate food for patients and staff, and in less-than-desirable conditions. I still recall seeing a full-term infant pass away because it wasn’t possible to control the baby’s body temperature in a nursery that was as cold inside as it was outside. But the nurses, with conviction, did what needed to be done; they performed at their best.

Best practices

In the words of a Thomas the Train song, “Accidents happen,” but they should not be routine! Fatigue contributes to errors, but errors can be avoided by initiating and adhering to best practices.

Best practices are aimed at creating a system-wide approach to safety and the creation of a safe environment that supports open dialogue about errors, their causes, and strategies for prevention. Analysis of errors is a best practice, and corrective action naturally follows.

Transparent communication and impact on safety

Communication is at the very core of safety. Effective communication between management and staff is essential to keep everyone informed and involved in the culture of safety. Regardless of the goal, all internal communications should follow a strategic plan to be successful. Employees are more likely to be engaged in the results if they feel involved. In nursing, staff members seek a leader with a transformational style. Staff members prefer not to be micromanaged; they want to be embraced for the value that they bring to the clinical setting, engaged actively, and empowered to succeed. Today’s transformational leaders have shifted from “management” to “leadership.” They are able to identify the changes needed, guide the change by inspiring followers, and create a sense of commitment to change. What better way is there to promote a positive, professional work environment? After all, if our end goal is to find and keep balance, we need to first find ourselves in a positive, professional work setting. We need to be led, not managed, and transparent communication allows that to happen.

Reduced performance

High levels of fatigue cause reduced performance and productivity and increase the risk of accidents and injuries. Fatigue affects the ability to think clearly. As a result, people who are fatigued are unable to gauge their own level of impairment. They are unaware that they are not functioning as well or as safely as they would be if they were not fatigued. A number of real-world mishaps have resulted from performance failures associated with operator sleepiness (Caldwell, Caldwell, & Schmidt, 2008). This is certainly true of the transportation industry.

Performance levels drop as work periods become longer and sleep loss increases. Staying awake for 17 hours has the same effect on performance as having a blood alcohol content of 0.05%. Staying awake for 21 hours is equivalent to a blood alcohol content of 0.1% (Lamond & Dawson, 1999). The most common effects associated with fatigue are:

- Sleepiness

- Lack of concentration

- Impaired recall

- Irritability

- Poor judgment

- Reduced ability to communicate with others

- Reduced fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination

- Reduced visual perception

- Slower response times

Rogers (2012) studied the impact of fatigue on officers of the law. Not only do these effects decrease performance and productivity within the workplace, but they simultaneously increase the potential for incidents and injuries to occur. Fatigued workers may place themselves and others at risk in the following situations:

- When operating machinery (including driving vehicles)

- When performing critical tasks that require a high level of concentration

- Where the consequence of error is serious, including death or disaster

In the past, the 40-hour workweek was routine. Law enforcement agencies typically deployed their patrol officers based on that schedule, followed by 2 days off. More recently, some agencies have adopted a compressed workweek (CWW) schedule in which officers work four 10-hour shifts per week or three 12-hour shifts plus adjusted time to equal 40 hours (Bambra, Whitehead, Sowden, Akers, & Petticrew, 2008). This certainly is not new to the health professions.

Even the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) has analyzed fatigue-related factors in accidents on domestic air carriers. And the media has focused on truck-driver fatigue-related accidents. Is the fatigued officer, pilot, driver, or healthcare provider fit for duty?

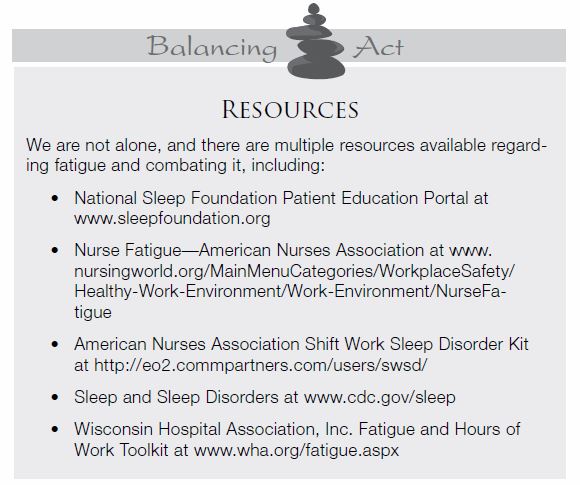

Standards and regulations to promote patient safety and resident alertness have addressed the number of hours worked. While resident working hours have been a topic of discussion for years, nurse fatigue and hours worked have also been studied extensively. The ANA Nurse Fatigue Panel, of which I am a part, has developed a position paper on fatigue (ANA, 2014b). However, by focusing on the hour factor alone, we neglect what we know about sleep and performance that could influence multiple human factors. The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2008) report on resident duty hours included a recommendation for 5-hour naps. As a student nurse, I recall many interns and residents napping on a stretcher in the hallway of our hospital wards; they did what they could to recover from fatigue.

Are mistakes caused by people or machinery? Think about how many times you have sought online support for a computer transaction—perhaps for an insurance claim. The “live” voice at the end of the line indicated that the “computer” made the mistake; we know all too well that the human being at the keyboard was the culprit.

A study found that four out of eight officers involved in on-the-job accidents and injuries were impaired because of fatigue (Dorrian et al., 2011). Such accidents include automobile crashes that were due to officers’ impaired eye-hand coordination and a tendency to nod off behind the wheel. Other work-related injuries come from accidents that occur when officers have impaired balance and coordination.

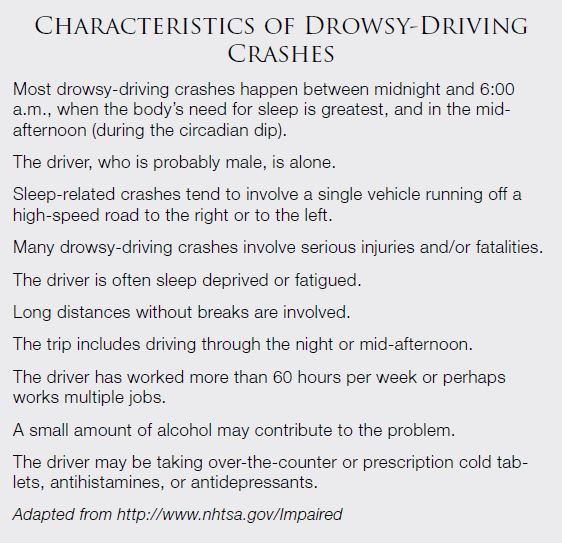

Drowsy driving

We have all experienced dozing off in a classroom—perhaps because of a boring instructor. We may also have experienced dozing off while driving a car because it was too warm or because we were exhausted. I know many folks who have been in accidents in which they hit the car in front of them simply because of tiredness. They may have opened the windows to allow cool air to enter the vehicle or cranked up the music to stay awake and hopefully to make it home safely. Singing, talking on the phone, slapping yourself in the face, and keeping a full bladder are all tactics that tired workers have used to keep themselves awake while driving home. Never say to yourself, “I am almost there; I can make it home.” It is no secret that one cannot and should not drive or operate machinery while tired.

Tragically, drowsy driving has taken far too many lives. Traffic crashes are the leading cause of death of young people in the United States, taking the lives of at least 5,600 teens each year according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA, 2013). And, each year drowsy-driving crashes result in at least 1,550 deaths, 71,000 injuries, and $12.5 billion in monetary losses. Unfortunately, many people do not realize how tired they are, and they do not think about the fact that their skills are reduced when they are sleep-deprived. If you are a truck driver or shift worker planning to catch up on some sleep this weekend, it might be wise to rethink exactly how you’re going to do that. Sleep must be a priority, like diet, water, and exercise.

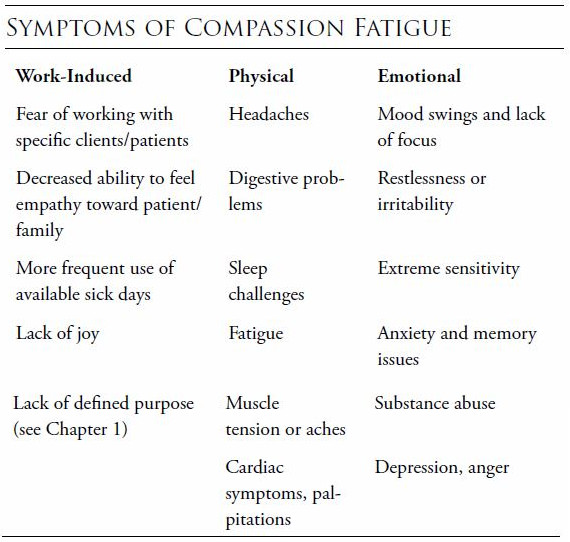

Compassion fatigue

Compassion fatigue is a combination of physical, emotional, and spiritual exhaustion associated with the care of patients with significant pain and physical distress (Lombardo & Eyre, 2011).

Identifying compassion fatigue

In any setting in which care is provided, compassion fatigue is a possibility. Mental health professionals, preceptors, and others can help to validate the presence of compassion fatigue. Awareness of the problem is critical to developing an intervention. As a student, I recall attempting to be all things to all people. We had no label for it at the time, but I was a candidate for compassion fatigue. I did not take a day off because I wanted to be there to feed a patient who was dependent on me. I took home patients’ laundry, and I did everything above and beyond the call of duty to provide care and service.

Triggers for compassion fatigue include:

- Evaluation of the work setting and conditions

- A tendency to become over involved

- Usual coping strategies and management of life crises

- Methods of self-care, if any, including massage, meditation, deep breathing

- Interest in enhancing personal and professional well-being

Interventions

Now that you are aware of the issue of compassion fatigue, either for yourself or a staff member, it is so important to intervene in some way. Simply talking about one’s feelings can be the first step. Be cognizant of resources within the work setting. Most employers have an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) as a part of the talent management or human resources department. EAPs can offer supportive counseling for either personal or work-related concerns. The EAP may provide lifestyle courses that address life-learning topics, such as managing time, balancing a budget, caring for an aging parent, communicating effectively, and reducing stress. These classes are designed to decrease stress, enhance work-life balance, and provide help for employees experiencing conditions such as compassion fatigue. See Chapter 8 for more on EAPs.

Dealing with compassion fatigue

How do we deal with the challenges? Some examples of helpful strategies might include changing work assignments or shifts; recommending time off or reducing overtime hours; encouraging attendance at a conference or personal development program; or becoming involved in a project of interest. These actions could contribute to work satisfaction, work balance, and a healthy attitude.

Embracing fatigue

We all need downtime. We all need positive self-care strategies and healthy rituals to cope with something like compassion fatigue. This includes activities that replenish personal energy levels and enhance overall well-being. A commitment to taking care of oneself includes having adequate nutrition, hydration, sleep, and exercise. The nurse may need to be encouraged to try a new approach to self-care, such as a yoga class, massage, meditation, or Tai-Chi. Some facilities have onsite relaxation or respite centers where staff may unwind. They may offer Reiki, light massage, or a healing touch treatment. If an entire area cannot be designated, perhaps a room can be transformed by adding soothing colors to the walls and providing calming music, a waterfall, and comfortable seating.

Alarm fatigue

Imagine the number of bells and whistles that are going off during a single shift. Hospitals are replete with noise; it is certainly not the place to go for an extended rest! Medical device alarms contribute to an environment that poses a significant risk to patient safety and anticipated outcomes.

Alarm fatigue is a national problem, specifically within the healthcare arena. The challenge with alarm desensitization is complex and relates to high false alarm rates, lack of standardization, and the plethora of alarming devices in clinical settings today.

Outcomes and impact

What are the hazards and how do they affect outcomes? Medical devices generate enough false alarms to create a reduction in response known as the “cry wolf effect.” Frequent alarms are distracting and interfere with thought processes; they may even lead to staff disabling important alarm systems. We know that we do not want to miss a beat; alarms are designed for high sensitivity so that this is possible. When the alarm is viewed as a nuisance, it may be ignored. What was intended to make the healthcare environment safer has now generated the opposite effect. Organizations committed to finding solutions have formed interdisciplinary alarm management teams to assess the risk and identify safe strategies for alarm reduction.

Injury

In addition to increased risk for errors and reduced job performance, drowsy driving and fatigue have major implications on the health of workers, especially nurses. Substantial scientific evidence links shift work and long hours to sleep disturbances, injuries, gastrointestinal and mood disorders, obesity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and adverse reproductive outcomes (Antunes, Levandovski, Dantas, Caumo, & Hidalgo, 2010; Brown et al., 2010; Bushnell, Colombi, Caruso, & Tak, 2010), some of which I discuss in more detail in the next few sections.

Fatigued workers need rest, breaks (including biological breaks), and time away from the workplace. The need for sleep is the second most powerful urge of the human body; it’s second only to the need to breathe. Imagine how you might feel and function after 24 sleepless hours. People aren’t designed for 24/7 operations. Work-related injuries are not a required part of the job; we all need balance between activity and recovery time in order to prevent injury. Repetitive work without regular breaks or rest can contribute to strains, sprains, poor posture, headaches, stress, and, of course, fatigue. Injuries may possibly be reduced by enforcing:

- Regular breaks and scheduled meal times

- Regular working hours

- Regular time away from the job, even if just for a few minutes (perhaps for a walk around the grounds)

Gastrointestinal and mood disorders

When we are exhausted, we are often too tired to eat. Our mood changes and we are irritable. This is fatigue at its worst. There is a direct link between blood sugar and mood. Carbohydrates are broken down into glucose and your brain runs on this type of fuel. The more unsteady your blood sugar supply, the more uneven your mood. Avoid overconsumption of “bad mood foods” such as wheat, rye, and barley. Gluten sensitivity may contribute to diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and other digestive challenges, even in the absence of diagnosed Celiac disease (Strawbridge, 2013).

The good news is that just as eating the wrong things (or not eating) can negatively effect your energy level and mood, taking in enough of the right things can help you. Let’s face it—what you eat will impact your ability to be well and to stay well; it will impact balance. You may have heard, “Give the body the right tools and it will do its best work.” It is true because making smart choices can boost both your mental and physical health.

There is good news, and that is that we do not have to think of achieving good health with drugs alone. There are natural solutions that I have used for years, and there are studies within the literature that attest to the benefits of a more holistic approach to well-being (Ernst, 2007; National Prevention Council, 2011). Let’s examine some of those approaches and how they impact our health outcomes.

Battling depression without drugs

Depression is a good starting point; when you view the drug advertisements in the media related to depression, you realize the depth of the health challenge. You also realize the depth of the toxicities and understand why the public seeks alternatives or more natural methods of coping. There have been six double-blind placebo controlled trials to date, five of which show merit. The first trial by Dr. Andrew Stoll from Harvard Medical School, published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, gave 40 depressed patients either omega-3 supplements or a placebo and found a highly significant improvement (Stoll et al., 1999). The next, published in The American Journal of Psychiatry, tested the effects of giving 20 people suffering from severe depression who were already on antidepressants but still depressed a highly concentrated form of omega-3 fat called ethyl-EPA versus a placebo. By the third week the depressed patients on the ethyl-EPA were showing major improvement in their moods whereas those on placebo were not (Nemets, Stahl, & Belmaker, 2002). A recent pooling of trials (a meta-analysis) which looked at all good quality trials of omega-3 fats and mood disorders concluded that omega-3 fats reduced depressive symptoms by an average of 53% and that there was as correlation between dose and depressive symptom improvement, meaning that higher dose omega-3 was more effective than a lower dose. Of those that measured the Hamilton Rating Scale, including one open trial that didn’t involve placebos, the average improvement in depression was approximately double that shown by antidepressant drugs and without the side-effects (Khan, Khan, Shankles, & Polissar, 2002). This may be because omega-3 fats help to build the brain’s neuronal (brain cell) connections as well as the receptor sites for neurotransmitters; therefore, the more omega-3 fats in your blood, the more serotonin you are likely to make and the more responsive you become to its effects (Agrawal & Gomez-Pinilla, 2012).

In terms of side effects, very occasionally, when starting omega-3 fish oil supplementation, some people can get slightly loose bowels or fish-tasting burps, but this is quite rare. Supplementing fish oils also reduces risk for heart disease, reduces arthritic pain, and may improve memory and concentration.

Both tryptophan and 5-HTP, both naturally occurring amino acids, have been shown to have an antidepressant effect in clinical trials, although 5-HTP is more effective (Turner, Loftis, & Blackwell, 2005). So how do tryptophan and 5-HTP compare with antidepressants? The natural approach may be better, simply because of decreased potential for side effects associated with drugs.

Because antidepressant drugs, in some sensitive people, can induce an overload of serotonin—a result called serotonin syndrome, which is characterized by feeling hot, having high blood pressure, and experiencing twitching and cramping of muscles, dizziness, and disorientation—a licensed independent practitioner should always direct the approach to care and monitor progress.

As for side effects, some people experience mild gastrointestinal disturbance on 5-HTP, which usually stops within a few days. Because there are serotonin receptors in the gut that don’t normally expect to get the real thing so easily, they can overreact if the amount is too high, resulting in transient nausea. If so, it helps to lower the dose or take it with food.

Exercise, sunlight, and reducing your stress level also tend to promote serotonin production.

Avoiding sugars and carbohydrates

Eating lots of sugar is going to give you sudden peaks and troughs in the amount of glucose in your blood, which can lead to symptoms that include fatigue, irritability, dizziness, insomnia, excessive sweating (especially at night), poor concentration and forgetfulness, excessive thirst, depression and crying spells, digestive disturbances, and blurred vision. Because the brain depends on an even supply of glucose, it is no surprise to find that sugar has been implicated in aggressive behavior, anxiety, depression, and fatigue.

Lots of refined sugar and refined carbohydrates (meaning white bread, pasta, rice, and most processed foods) is also linked with depression because these foods not only supply very little in the way of nutrients but they also use up the mood-enhancing B vitamins. (Turning each teaspoon of sugar into energy requires B vitamins.) In fact, a study of 3,456 middle-aged civil servants, published in The British Journal of Psychiatry, found that those who had a diet that contained a lot of processed foods had a 58% increased risk for depression, whereas those whose diet could be described as containing more whole foods had a 26% reduced risk for depression (Borchard, 2011).

The best way to keep your blood sugar level even is to eat what is called a low glycemic load (GL) diet and avoid, as much as you can, refined sugar and refined foods. Instead, eat whole foods, fruits, vegetables, and regular meals. The book, The Low-GL Diet Bible by Patrick Holford (2009) explains exactly how to do this, so that book is a great resource if you really want to improve your blood sugar balance. Caffeine also has a direct effect on your blood sugar and your mood and is best kept to a minimum, as is alcohol (Smith, Sutherland, & Christopher, 2005).

The best part of balancing your blood sugar—no side effects.

Addressing vitamin D deficiencies

You are most at risk for vitamin D deficiency if you are elderly (because your ability to make it in the skin reduces with age), dark-skinned (you require up to six times more sunshine than a light-skinned person to make the same amount of vitamin D), overweight (your vitamin D stores may be tucked away within your fat tissue), or you tend to shy away from the sun by covering up and using sunblock. Of course, you should never risk your skin health by getting sunburned. The National Institute of Health Fact Sheets on Vitamin D offer quick facts and suggestions on handling deficiencies (2014). For example, vitamin D is readily available in milk and other dairy products, mushrooms, beef liver, as well as in supplements.

Obesity

So, you attributed that belly fat to a mid-life crisis or hormonal challenge! Look at the pattern of sleep apnea, daytime sleepiness, and fatigue. Now think about your visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and other health issues! Is there a correlation? Could these factors be interconnected? We already know that obesity is a significant risk factor for sleep apnea. Some researchers believe that it is visceral fat, rather than generalized obesity, that predisposes people to the development of sleep apnea (Vgontzas et al., 2000).

But, how about if we think of obesity and fatigue as interrelated simply because we did not take the time for a decent, healthy meal? Perhaps we inhaled our fast food at the desk or nurse’s station. Perhaps on your shift, there is no healthy food available to you, and you succumb to the snack bar or candy machine for a sugar high. This can clearly contribute to obesity, and when your weight is higher than normal, you can also suffer from increased fatigue. What might not tire someone else could very well tire you.

Cardiovascular disease

A lack of quality sleep can certainly contribute to high blood pressure and subsequent heart disease, but it can be a vicious circle. When you are persistently tired or chronically fatigued, you will be less healthy. Fatigue is a frequent sign of heart disease, especially in women.

If you have an existing cardiac problem, you are more likely to experience fatigue. Fatigue may be drug induced or lifestyle induced. Remember that fatigue is a symptom—something that is felt, such as a headache or dizziness. It is not a sign that can be detected on examination. So, know your body, report your symptoms, and be well.

What can you do to keep yourself heart healthy, fatigue-free, and feeling well? You can ensure adequate rest, hydration, nutrition, and exercise. You can make a concerted effort to take good care of your body so that your body will take good care of you.

"When I’m tired, I rest. I say, 'I can’t be a superwoman today.'"

–Jada Pinkett Smith

Fatigue countermeasures

Fatigue countermeasures can be as simple as taking breaks. In patient care settings, per diem or float pool nurses can work during meal periods. Creative scheduling and nontraditional hours are an option for those who prefer to work partial shifts but want to remain active. A fatigue reduction management system (FRMS) is essential, regardless of the industry. There are several ways to structure an effective FRMS. One method was proposed by the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) in their Guidance Statement on Fatigue Risk Management in the Workplace (ACOEM, 2012).

We can push our bodies and our minds just so far before they will fail us. Fatigue countermeasure programs should be offered by employers. In healthcare, they might include providing adequate staffing, ensuring breaks and meal periods, offering sleeping accommodations (such as a recliner and a timer), and establishing nap policies. The employee’s responsibility is to obtain sufficient sleep prior to beginning a shift.

Institutional countermeasures include defining roles and responsibilities, training staff, assessing and reducing risk, defining performance indicators, and investigating sentinel events.

Stakeholders

We all have a stake in the challenge; we are all the solution. Stakeholders are people or organizations that are invested in the program, are interested in the results of the evaluation, and/or have a stake in what will be done with the results of the evaluation. Representing their needs and interests throughout the process is fundamental to good program evaluation and to an effective countermeasure program.

In my field, which is health and well-being, the stakeholders are employers, policymakers, researchers, professional societies, caregivers, advocacy groups, providers, patients, and payers. Expectations may be high, and may differ substantially. However, we all want the same result: quality, safety, and good outcomes. By identifying and engaging those involved, we support collaboration.

This chapter focused on fatigue and its impact on work, safety, well-being, and stress. Remember that stress is often manifested by emotional as well as physical symptoms, and we covered them all. You must assume responsibility for fatigue; it is not the work of the employer alone. Rather, steps that you take to maintain your own health, to avoid drowsiness and to be responsible, play a significant role in balance. And, this chapter examined those health issues like gastrointestinal, mood, depression, obesity, cardiovascular and more. Assuming a natural approach for health and wellness allows you to balance traditional allopathic methods with an integrative approach that considers the whole body and your behaviors.

The core issue here was fatigue; we all have a stake in the challenge; we are all the solution. We can find balance by knowing our body and its response to the stressors we face. We can find balance by taking steps to minimize fatigue.

Click for information on purchasing B Is for Balance, Second Edition

Sharon M. Weinstein, MS, RN, CRNI, FACW, FAAN, is President and founder of SMW Group LLC, Core Consulting Group, and the Global Education Development Institute. Weinstein is the author of nine texts and more than 160 peer-reviewed publications. A member of the National Wellness Institute, Infinity Foundation, Chicago Healers, The American College of Wellness, the American Nurses Association, and the American Holistic Nurses Association, Weinstein earned her spot as the go-to professional for education, resources, well-being, and work/life balance. She is the founder of the Integrative Health Forum (IHF, www.ihfglobal.com), an interdisciplinary alliance of licensed healthcare professionals whose mission is to serve the professionals and associations that promote health and well-being in individuals, organizations, and communities around the globe. She is an independent founding member of Alphay, a global health and wellness company. Recently elected to a leadership role within the American Holistic Nurses Association (AHNA) and to the board of directors of the National Speakers Association (NSA), she is past president of the Infusion Nurses Society (INS) and past chair of the Infusion Nurses Certification Corporation (INCC). Weinstein serves as a member of the Expert Panel on Global Nursing/American Academy of Nursing.

References

Agrawal, R., & Gomez-Pinilla, F. (2012). “Metabolic syndrome” in the brain: Deficiency in omega-3-fatty acid exacerbates dysfunctions in insulin receptor signaling and cognition. The Journal of Physiology. Retrieved by http://jp.physoc.org/content/early/2012/03/31/jphysiol.2012.230078.abstract

American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM). (2012). Fatigue risk management in the workplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 54(2), 231-258.

American Nurses Association (ANA). (2014a). Health & safety: Workplace fatigue. Retrieved from http://nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/

WorkplaceSafety/Healthy-Work-Environment/Work-Environment/NurseFatigue

American Nurses Association (ANA). (2014b). Position paper on nurse fatigue.

Antunes, L. C., Levandovski, R., Dantas, G., Caumo, W., & Hidalgo, M. P. (2010). Obesity and shift work: Chronobiological aspects. Nutrition Research Reviews, 23(1), 155-168.

Bambra, C. L., Whitehead, M. M., Sowden, A. J., Akers, J., & Petticrew, M. P. (2008). A hard day’s night? The effects of compressed working week interventions on the health and work-life balance of shift workers: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 62(9), 764-777.

Barker, L. M., & Nussbaum, M. A. (2011). Fatigue, performance and the work environment: A survey of registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(6), 1370-1382.

Borchard, T. (2011). Why sugar is dangerous to depression. PsychCentral. Retrieved from http://psychcentral.com/blog/archives/2011/07/13/

why-sugar-is-dangerous-to-depression/

Brown, D. L., Feskanich, D., Sanchez, B. N., Rexrode, K. M., Schernhammer, E. S., & Lisabeth, L. D. (2010). Rotating night shift work and the risk of ischemic stroke. American Journal of Epidemiology, 169(11), 1370-1377.

Bushnell, P. T., Colombi, A., Caruso, C. C., & Tak, S. (2010). Work schedules and health behavior outcomes at a large manufacturer. Industrial Health, 48(4), 395-405.

Caldwell, J. A., Caldwell, J. L., Schmidt, R. M. (2008). Alertness management strategies for operational contexts. Sleep Medicine Review, 12(4), 257-273.

Dorrian, J., Lamond, N., Dawson, D. (2000). The ability to self-monitor performance when fatigued. Journal of Sleep Research. 9(2), 137-144.

Dorrian, J., Paterson, J., Pincombe, J., Grech, C., Rogers, A. E., & Dawson, D. (2011). Sleepiness, stress, and compensatory behaviors in nurses and midwives. Revista de Saute Publica (Journal of Public Health, Brazil), 45(5), 922-930

Drake, D. A., Luna, M., Georges, J. M., & Steege, L. M. (2012). Hospital nurse force theory: A perspective of nurse fatigue and patient harm. Advances in Nursing Science, 35(4), 305-314.

Ernst, E. (2007). Herbal remedies for depression and anxiety. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13, 312-316. Retrieved from http://apt.rcpsych.org/

content/13/4/312.full

Hendren, R. (2011, May 17). How nurse executives can help tired nurses. Retrieved from www.healthleadersmedia.com/Page-1/NRS-266247/

How-Nurse-Executives-Can-Help-Tired-Nurses

Holford, P. (2009). The Low-GL Diet Bible. London: Little, Brown Book Group.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (2008). Resident duty hours: Enhancing sleep, supervision, and safety. Retrieved from http://iom.edu/~/media/

Files/Report%20Files/2008/Resident-Duty-Hours/residency%

20hours%20revised%20for%20web.pdf

The Joint Commission (TJC). (2011). Health care worker fatigue and patient safety. Sentinel Event Alert, 48. Retrieved from www.jointcommission.org/

assets/1/18/sea_48.pdf

Khan A., Khan, S. R., Shankles, E. B., & Polissar, N. L. (2002). Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, the Hamilton Depression rating scale and the Clinical Global Impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17(6), 281-285.

Lamond, N., & Dawson, D. (1999). Quantifying the performance impairment associated with fatigue. Journal of Sleep Research, 8(4), 255-262.

Lerman, S. E., Eskin, E., Flower, D. J., George, E. C., Gerson, B., Hartenbaum, N., & Moore-Ede, M. (2012). Fatigue risk management in the workplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 54(2), 231-258.

Leung, A., Chan, C., Ng, J., and Wong, P. (2006). Factors contributing to officers’ fatigue in speed maritime craft operations. Applied Ergonomics, 37(5), 565–576.

Lombardo, B., & Eyre, C. (2011). Compassion fatigue: A nurse’s primer. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 16(1). Retrieved from http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/

ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-16-2011/No1-Jan-2011/Compassion-Fatigue-A-Nurses-Primer.html

Mayo Clinic Staff. (2014). Psychological fatigue. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/symptoms/fatigue/basics/definition/sym-20050894

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). (2013). Early estimate of motor vehicle traffic fatalities in 2012. Traffic Safety Facts: Crash Stats. Retrieved from http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811741.pdf

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2014). Vitamin D: Fact sheet for consumer. Retrieved from http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-QuickFacts/

Natural Prevention Council. (2011). National prevention strategy—America’s plan for better health and wellness. Retrieved from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/initiatives/prevention/strategy/report.pdf

Nemets, B., Stahl, Z., & Belmaker, R. H. (2002). Addition of omega-3 fatty acid to maintenance medication treatment for recurrent unipolar depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(3), 477-479.

Reed, K. (2013). Nursing fatigue and staffing costs: What’s the connection? Nursing Management, 44(4), 47-50.

Rogers, A. E. (2012). Healthcare work schedules. In P. Carayon (Ed.), Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in health care and patient safety (pp. 199-208). New York: Taylor & Francis Group.

Smith, A., Sutherland, D., & Christopher, G. (2005). Effects of repeated doses of caffeine on mood and performance of alert and fatigued volunteers. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 19(6), 620-626.

Stoll, A., Severus, E., Freeman, M. P., Rueter, S., Zboyan, H. A., Diamond, E.,...Marangell, L. B. (1999). Omega 3 fatty acids in bipolar disorder: A preliminary double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(5), 407-412. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.407.

Strawbridge, H. (2013). Going gluten-free just because? Here’s what you need to know. Harvard Health Publications: Harvard Medical School. Retrieved from http://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/going-gluten-free

-just-because-heres-what-you-need-to-know-201302205916

Turner, E. H., Loftis, J. M., & Blackwell, A. D. (2005). Serotonin a la carte: Supplementation with the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. http://www.academia.edu/280135/Serotonin_a_la_carte_Supplementation_

with_the_serotonin_precursor_5-hydroxytryptophan

Vgontzas, A. N., Papanicolaou, D. A., Bixler, E. O., Hopper, K., Lotsikas, A., Lin, H.,...Chrousos, G. P. (2000). Sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness and fatigue: Relation to visceral obesity, insulin resistance, and hypercytokinemia. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 85(3), 1151-1155.

WebMD. (2013). Weakness and fatigue. Retrieved from http://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/weakness-and-fatigue-topic-overview