It is always by accident we meet. (Republished from 2017.)

Before I was a nurse, I was a firefighter/paramedic. We had a saying back in those days, “When you give a guy a white shirt, he forgets where he came from,” referring to someone moving into a management position. I promised myself I would not be that guy. Eventually, the time came to leave a secure and prized job with a good pension to further my passion for helping others. That led me to the nursing profession. This story is about remembering our nursing roots.

Recently, I was on a trip to England, and, as I so often do, I ran into Florence Nightingale. It is always by accident we meet. The first time I serendipitously ran into her, I was in London, just a few blocks from Trafalgar Square. I looked up and discovered I was standing at the base of a monument dedicated to her.

Recently, I was on a trip to England, and, as I so often do, I ran into Florence Nightingale. It is always by accident we meet. The first time I serendipitously ran into her, I was in London, just a few blocks from Trafalgar Square. I looked up and discovered I was standing at the base of a monument dedicated to her.

The next time was a few years later. Again, I was in London. While trying to find a Tube station—subway entrance to us Yanks—I found myself in front of her museum. Of course, I went in and spent a few hours. In doing so, I was reminded of one of Nightingale’s famous quotes: “I attribute my success to this—I never gave or took any excuse.” I have put this into practice ever since, and there is no doubt it has positively impacted my career.

On my most recent encounter with Miss Nightingale—just a few weeks ago—I was visiting the beautiful English countryside. I was on a family holiday, giving little thought to anything work-related. In fact, it was the first time in 20 years I had not taken a computer or “work” on vacation. As my wife and I often do, we visited a historical site, this time a stately home preserved by the National Trust and its wonderful volunteers.

Claydon House

The name of this impressive home is Claydon House, owned by the Verney family. In 1858, Lord Harry Verney married Parthenope Nightingale, who owned this lovely home. And yes, she was the sister of the grand Lady of the Lamp. It turns out, after returning from the Crimea, Florence Nightingale spent her summers at Claydon House.

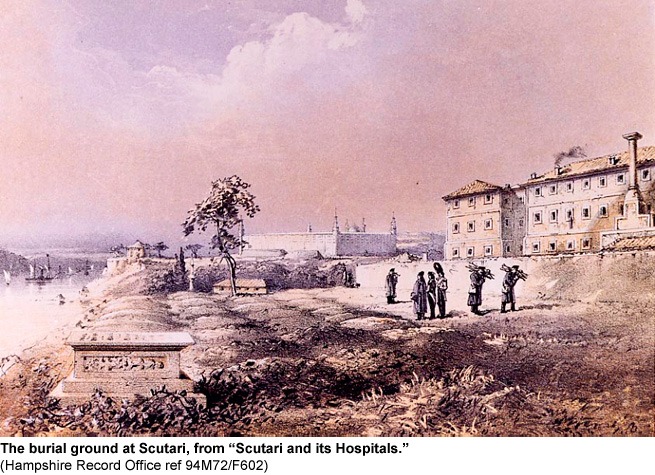

The artifacts in the home are amazing. The collection is still owned by the Verney family and includes writings in Florence’s hand. There is a lamp from the Crimea (which looks nothing like the lamp we picture her with) along with many sketches, including one of Nightingale riding sidesaddle across the Crimea. No wonder she had a bad back. There’s a lock of her hair, a sash she wore during her time at Scutari hospital in Turkey, where, in 1854, army commanders turned Nightingale and 38 other nurses away, rejecting their help. Because of Nightingale’s never-take-no-for-an-answer approach to life, we all know how that turned out.

There is a shriveled orange given her by a soldier. There’s a picture of a pin created for her by Queen Victoria—a pin because women in those days could not be awarded medals—along with the accompanying letter from the queen. I saw a picture of Miss Nightingale and a class of graduating nursing students that was taken outside of Claydon House just before the customary tea she held for each class of graduates. This tradition continues today at ceremonies when new members are inducted into the Honor Society of Nursing, Sigma Theta Tau International. I could go on for hours about the treasures I had the pleasure of viewing. The greatest treasure, however, wasn’t contained in a glass case or displayed on a pedestal. It was the history embodied in one of the docents at Claydon House—Glenys Warlow.

“The Great Lady”

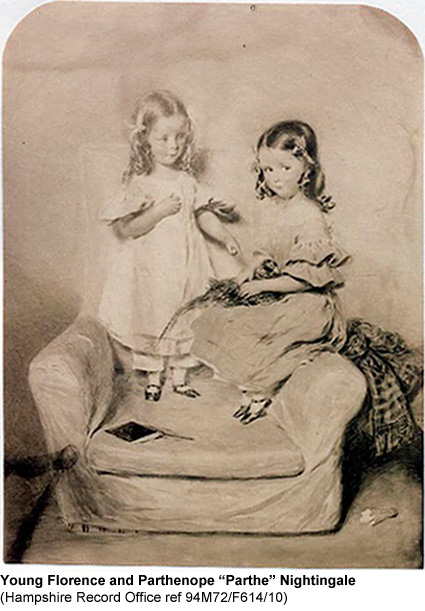

I asked Warlow to tell me about Florence Nightingale. She asked where she should start, to which I replied, “Wherever you like.” She began by telling me about Florence’s upbringing. She reminded me that the reason she was so well educated is because she came from a very affluent family. She asked her father to allow her to continue her education, which he did, and her education would prove significant in influencing the way we treat patients today. Warlow also reminded me that Nightingale’s decision to go into nursing flew in the face of her family because women of her status did not do that kind of work. We all know how that went.

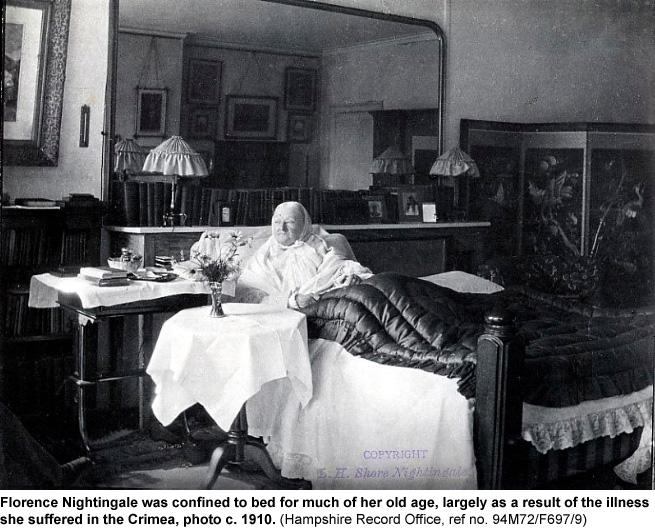

As Warlow guided me through the room, she gave context to treasures about which I never would have known. I don’t know if she realized that, in explaining part of Florence’s work, she was talking about something we are still working on today—reducing cost per patient day. She shared with me the community health curriculum “The Great Lady”—as Warlow referred to her—developed after returning from the Crimea. As she talked about Florence’s later years, including her back-breaking work and travel by horseback, it became clear why it was necessary for Nightingale to spend much of her later years in repose.

I spent more than an hour with Warlow, who, by the way, is not a nurse. However, she knows more about the roots of the nursing profession than many nurses I know. Her passion for Miss Nightingale filled my heart.

Thank you, Glenys, for all the lives you touch as you volunteer in the spirit of Florence Nightingale. Thank you for bringing her history to life so others might consider walking in her footsteps and for reminding me where my passion for nursing comes from—a passion for changing people’s lives no matter the roadblocks that may be placed in front of me.

O yes, and thanks, Miss Nightingale. I will not forget my roots!

Kenneth W. Dion, PhD, MSN/MBA, RN, founder of Decision Critical Inc., is treasurer of the board of directors of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing (Sigma). He is past president of the board of trustees of the Foundation of the National Student Nurses' Association and past chair of the board of directors of Sigma Theta Tau International Foundation for Nursing.

Photos used with permission. To access the home page of Hampshire Archives and the Hampshire Record Office, click here. To access “Florence Nightingale,” a document published by the Hampshire Record Office, Archive Education Service, click here. To access additional information about Florence Nightingale from Hantsweb, click here and select “Florence Nightingale, 1820-1910.” Her biographic information is organized under the following headings: “The early years,” “Florence growing up,” “Florence and the Crimea,” “Florence after the Crimea,” and “The final years.”

Editor's note: This article has been reposted because of technical problems with the RNL website when the article was first published on 20 July 2017.