This chapter from Transforming Nursing Through Knowledge,

a Sigma book, discusses key aspects of the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario's (RNAO) Best Practice Spotlight Organization (BPSO) Designation, including its initial vision, main objectives, and current requirements.

Learning objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

-

Describe the RNAO Best Practice Spotlight Organization (BPSO) Designation as a global meso- and macro-level knowledge translation (KT) strategy

-

Identify key requirements of the BPSO Designation and how they are informed by implementation science

-

Understand how the Knowledge-to-Action framework guides the work of the BPSOs and RNAO’s consultation and approaches for support

-

Discuss the importance of using a change management approach in BPG implementation activities and how that is addressed in the BPSO Designation

-

Outline how the types and models of BPSO contribute to widespread Best Practice Guideline (BPG) uptake and sustained use

-

Determine factors that contribute to the success of BPSOs in implementing and sustaining BPGs

-

Gain an appreciation of collective identity and how it is cultivated amongst BPSOs globally

Introduction

Introduction

In 2003, RNAO launched a highly successful organizational knowledge-transfer strategy: the Best Practice Spotlight Organization (BPSO) Designation. Through this strategy, service and academic organizations formally partner with RNAO to systematically implement RNAO’s clinical Best Practice Guidelines (BPG)—augmented with System and Healthy Work Environment guidelines; sustain and spread the use of BPGs; and create a culture of evidence-based practice (Bajnok, Grinspun, Lloyd, & McConnell, 2015). Academic BPSOs integrate RNAO’s evidence-based guidelines throughout the curriculum. In the ensuing years, the BPSO Designation has:

-

Been awarded to health service organizations in all sectors and in academic institutions

-

Involved nurses, faculty, students, and other healthcare professionals (including physicians, social workers, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech therapists, dieticians, and nonregulated staff)

-

Spread to 12 countries around the world

-

Been the impetus for implementation of all of RNAO’s 41 clinical and 12 System and Healthy Work Environment BPGs

-

Resulted in changes in practice and the work environment the world over

-

Improved health and clinical outcomes and quality of life for clients

-

Enhanced organizational performance

-

Contributed to healthcare cost savings

This chapter discusses key aspects of the BPSO Designation, including its initial vision almost 15 years ago (Di Costanzo, 2013; Grinspun, 2011), its key objectives, current requirements, and place in the global healthcare community today. The chapter concludes with a look at the future in relation to sustaining BPSO and BPSO Host Designates and maintaining quality.

Why BPSOs

In 2002, following the preparation of numerous BPG Champions (Grinspun, Virani, & Bajnok, 2002), to help implement the first published RNAO BPGs, it became clear that Champions, while necessary to evidence use, were not sufficient to create a sustained organizational culture of evidence-based practice. Nor could they alone make new practices and the use of new knowledge “stick” within their practice area and across the organization. It was obvious that enduring practice change took a team and consideration at multiple levels in an organization. In addition, it took concerted effort, organizational commitment, leadership, and knowledge about both best clinical evidence and best evidence in implementation science (Grinspun, 2011; Grinspun, Melnyk, & Fineout-Overholt, 2014; Higuchi, Davies & Ploeg, 2017; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2015; Melnyk et al., 2016; Ploeg, Davies, Edwards, Gifford, & Miller, 2007).

RNAO’s vision was to foster evidence-based organizations so that BPGs could be readily implemented using the Champions and other members of the team with the goal of achieving better client, provider, organizational, and system outcomes. Central to the vision was the rigorous BPG development process that RNAO had honed over the previous 5 years (Bajnok et al., 2015; Grinspun, 2011; Grinspun et al., 2014; Grinspun et al., 2002); the early attention RNAO paid to moving the best evidence into daily practice by building individual capacity; and the wide dissemination of guidelines through its broad network of nurses, healthcare professionals, and health system and policy stakeholders (Grinspun, Lloyd, Xiao, & Bajnok, 2015).

Through feedback from Champions and specially trained Clinical Resource Nurses, RNAO began to cultivate opportunities to engage with entire organizations to support them in key activities to implement Best Practice Guidelines throughout their institutions. As a result of these early activities, the BPSO Designation was conceived and inaugurated in 2003 (Bajnok et al., 2015; Di Costanzo, 2013; Grinspun, 2011) as an opportunity for healthcare organizations to formally partner with RNAO to systematically implement and sustain BPGs in practice and evaluate their impact. The BPSO Model is a practice model that incorporates structures, processes, and evaluation methods to support sustained use of Best Practice Guidelines and deliver improved outcomes for patients, providers, and the organization.

Through feedback from Champions and specially trained Clinical Resource Nurses, RNAO began to cultivate opportunities to engage with entire organizations to support them in key activities to implement Best Practice Guidelines throughout their institutions. As a result of these early activities, the BPSO Designation was conceived and inaugurated in 2003 (Bajnok et al., 2015; Di Costanzo, 2013; Grinspun, 2011) as an opportunity for healthcare organizations to formally partner with RNAO to systematically implement and sustain BPGs in practice and evaluate their impact. The BPSO Model is a practice model that incorporates structures, processes, and evaluation methods to support sustained use of Best Practice Guidelines and deliver improved outcomes for patients, providers, and the organization.

BPSO objectives

The specific objectives of this innovative BPG uptake endeavour are to:

-

Establish dynamic, long-term partnerships that focus on making an impact on patient care through supporting knowledge-based nursing practice

-

Demonstrate creative strategies for successfully implementing nursing Best Practice Guidelines at the individual and organizational levels

-

Establish and deploy effective approaches to evaluate implementation activities, utilizing structure, process, and outcome indicators

-

Identify effective strategies for system-wide dissemination of guideline implementation and outcomes

Selecting the BPSOs

Beginning in 2003, the first BPSOs were selected through a competitive request-for-proposal application process. This resulted in nine BPSOs representing sectors including home healthcare, acute care, and rehabilitation care in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. These pioneer BPSOs paved the way for the now-coveted BPSO Designation. From the outset there were very specific supports offered by RNAO and clear deliverables expected of the BPSOs.

Today, as in previous years, through the formal application process, applicants are required to demonstrate their commitment to engaging in the BPSO Designation at all levels in the organization, their short- and long-term objectives for BPSO, as well as their experiences and characteristics that will ensure success. Organizations also identify which BPGs they have selected to implement and how they were chosen. Over the ensuing years, the process has become more refined and rigorous; however, the key elements of organizational commitment and intent to sustain this work have been consistent, as has been the provision of RNAO coaching and consultation support and attention to principles of knowledge translation (KT).

Due to the high interest in the BPSO Designation in Canada and around the world, a number of information resources have been designed for potential BPSOs such as webinars, question-and-answer sessions, in person presentations, the BPSO website, and the “Steps to Becoming a BPSO” flyer (see Appendix A to view a copy of the flyer). They inform and support the application process for organizations that see the high value of the BPSO Designation, as expressed in the quote below by a chief nursing executive at a large hospital.

In their evaluation, Ploeg et al. (2007) found that factors at the individual, organizational, and environmental (systems) level influenced BPG implementation, many of which are foundational to the BPSO Designation. These include leadership support, Champions, teamwork and collaboration, professional association support, and inter-organizational collaboration and networks.

The BPSO Designation

Fifteen years later, the BPSO Designation is well recognized around the world and acknowledged as an award-winning innovation (Health Council of Canada, 2012; Kirschling & Erikson, 2010; WHO, 2015) that is closing the gap between the knowledge we have and how we use it in our practice (Melnyk, 2017).

As BPSOs, organizations agree to engage in a 3-year qualifying experience that is formalized as a partnership and delineated in a signed BPSO Agreement between the organization and the RNAO (RNAO, 2017a). The elements of the agreement include what the organization (BPSO) commits to and what supports the RNAO will provide. The mutual mandate is that the organization develops a supportive and sustainable infrastructure; builds capacity; implements multiple BPGs; disseminates the processes and outcomes of their BPSO activities; and evaluates the impacts on practice, clients, and the organization as a whole. These are recommended organizational strategies based in implementation science that contribute to building environments for evidence-based practice to flourish and health outcomes to improve (Grinspun et al., 2014; Melnyk, 2014).

Following the 3-year qualifying period, pending achievement of all required deliverables, the organization becomes a Designated BPSO. This recognition acknowledges the organization’s achievements in the systematic implementation and evaluation of evidence-based practices while demonstrating an evidence-based culture. As a BPSO Designate, the engagement is ongoing as BPSOs focus on sustaining the practice changes they implemented, spreading their work, and implementing new BPGs. They also continue contributing data to NQuIRE, RNAO’s robust international data system for measuring BPG impacts on clients and providers (Grinspun et al., 2015), and myBPSO, RNAO’s electronic reporting system for BPSOs. In addition, BPSO Designates become mentors for new BPSO organizations locally, nationally, and internationally—a much-needed resource for those organizations starting to implement best practices (Bajnok et al., 2015; Melnyk, 2014). The BPSO Designation is renewed every 2 years based on achievement of the requirements.

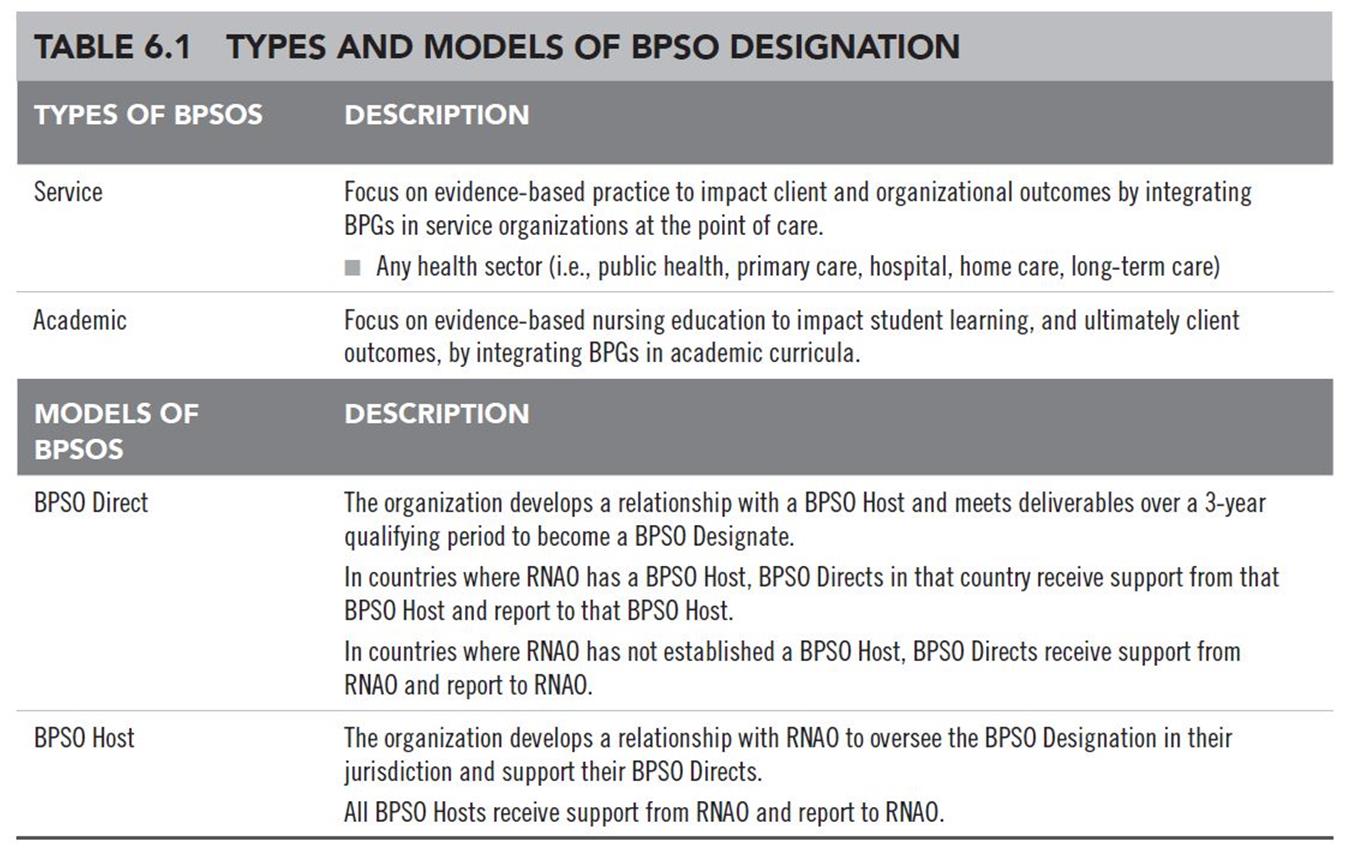

The BPSO Host Model

The RNAO BPSO Designation has experienced a very rapid spread globally, which precipitated RNAO to redesign the BPSO Designation in 2012 to include opportunities for broad global support and spread through the BPSO Host Model—a type of BPSO satellite (Albornos-Munoz, González-María, & Moreno-Casbas, 2015; Bajnok et al., 2015; Grinspun, 2011). The BPSO Hosts support organizations in their jurisdiction to become BPSOs and work directly with them. BPSO Direct organizations focus on evidence-based practice in their own institutions; they receive support from and report to a BPSO Host.

The BPSO Hosts currently established represent government agencies, academic conglomerates, regulatory bodies, and labour unions. The requirements for success as a BPSO Host are that they must:

-

Demonstrate capacity to engage organizations in their jurisdiction to become BPSO Directs with them

-

Request and review applications through a request-for-proposal process

-

Formalize relationships with selected organizations through a BPSO Agreement

-

Provide support to their BPSO Directs to achieve outcomes

-

Monitor the outcomes achieved

-

Report to RNAO through myBPSO, as a BPSO Host and on behalf of all its BPSO Direct organizations

-

Measure and report on outcomes

BPSO Hosts enter into a BPSO Host Agreement with RNAO (RNAO, 2017b), committing to use RNAO’s methodologies and materials and RNAO’s approaches to coaching, monitoring, and evaluation.

BPSO Hosts meet regularly with RNAO to share successes and challenges and gain support for their Host activities. To date, Spain (through the Nursing and Healthcare Research Unit [Investén-iscci] Institute of Health Carlos III), Australia (through the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation [ANMF]—SA Branch), and Italy (through the Collegio IPASVI Milano—Lodi—Monza e Brianza), amongst others, have been involved in the BPSO Designation through the BPSO Host Model. These BPSO Hosts, with RNAO’s support, lead the BPSO Designation in their jurisdictions and have successfully initiated and sustained this innovative and highly effective organizational KT strategy. Below is a quote from the BPSO Host Sponsor and the BPSO Host Lead in Italy reinforcing pride in being a BPSO Host and the impact of their work with outcomes apparent in their BPSO Directs.

New BPSO Hosts are currently being developed in Chile, Nova Scotia (Canada), and Peru. Table 6.1 summarizes the various types and models of BPSOs within the BPSO Designation.

BPSO implementation strategies

BPSO implementation strategies

The implementation consultation and coaching strategies used by RNAO and the specific BPSO Agreement requirements are grounded in implementation science (Gallagher-Ford, 2014; Grinspun et al., 2014; RNAO, 2012; Stetler, Richie, Rycroft-Malone, & Charns, 2014; Straus, Tetroe, & Graham, 2013). The following seven implementation strategies are embedded in the formal agreements organizations sign with RNAO once selected to be a BPSO (Bajnok et al., 2015):

-

Use a systematic, planned approach to implementation (RNAO, 2012)

-

Incorporate change principles in the guideline implementation process (Grol, Wensing, Eccles, & Davis, 2013; Haines, 2005; Heath & Heath, 2010; Kotter, 2012)

-

Engage leaders in all roles, both formal and informal (including BPSO Sponsors, BPSO Leads, Champion Leaders, Champions, BPG Leaders, and BPSO Steering Committee members), in all stages of BPG implementation (Aarons et al., 2016; Gifford, Davies, Tourangeau, & Lefebre, 2011; Higuchi et al., 2017; Stetler et al., 2014; Straus et al., 2013)

-

Align BPG implementation to the organization’s priorities to include the vision, mission, and strategic plan; quality-improvement initiatives; and government directives (Higuchi, Downey, Davies, Bajnok, & Waggott, 2013; Melnyk, 2014; Ploeg et al., 2007)

-

Select approaches to implementation informed by assessments of facilitators and barriers to knowledge uptake, and level of knowledge of the practice change (RNAO, 2012; Straus et al., 2013)

-

Integrate BPG recommendations into organizational processes, structures, and roles to enable dynamic sustainment (Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, 2013; Maher, Gustafson, & Evans, 2010)

-

Interact with a broader network of organizations striving for similar goals related to creating evidence-based cultures and implementing evidence-based guidelines (Melnyk, 2014; Straus et al., 2013)

RNAO coaching and consultation

The BPSO Host Coaches, including the RNAO Coaches working with their BPSO Directs, use the RNAO (2012) Toolkit: Implementation of Best Practice Guidelines and the Knowledge-to-Action framework (Straus et al., 2013) to guide their regular consultative sessions with BPSOs. This assists the BPSO Directs in making progress to achieve the BPSO requirements and deliverables over the 3-year period prior to designation. These deliverables are monitored by the BPSO Hosts and by RNAO for their BPSO Directs.

The monitoring process occurs in a variety of ways as established by BPSO Hosts to mirror the processes used by RNAO. These include regular meetings with Coaches, scheduled presentations to the BPSO knowledge exchange networks required in each BPSO Host jurisdiction, and semi-annual written reports to the BPSO Host (or to RNAO in cases where there is not a jurisdictional Host).

All BPSOs submit their reports through myBPSO, the online reporting system launched by RNAO in October 2015 to capture the specific deliverables related to guideline implementation, capacity development, dissemination, sustainability, and evaluation. The report auto-populates with previously inputted data, so BPSO Leads need to populate reports with new information only. The frequency of reporting is either biannually, or in the case of Designated BPSOs, annually. The evaluation data and other relevant contextual information from myBPSO are critical complements to NQuIRE’s indicator data. During the 3-year predesignation period, the formal BPSO Agreement is renewed annually pending performance reviews. Following designation, agreements are renewed every 2 years, again based on achievement of deliverables. These processes are the same for service and academic BPSOs.

A systematic implementation process

A systematic implementation process

Elements of the Toolkit (RNAO, 2012) that are part of the BPSO performance expectations and used as indicators of success are outlined below. These are described in detail in Chapter 4, Forging the Way with Implementation Science. The Toolkit (RNAO, 2012), a handbook of implementation science for BPG uptake, informs the curriculum for the RNAO BPG Champion program and the RNAO Clinical BPG Institute, both of which inform the BPSO Orientation Program. The elements are derived from the Knowledge-to-Action Model (Graham et al., 2006; Straus et al., 2013) and include:

-

Leaders at all levels make a commitment to support facilitation of guideline implementation.

-

Guidelines are selected for implementation through a systematic, participatory process.

-

Specific guideline recommendations are tailored to the local context.

-

Stakeholders that will be impacted by the implementation of the guidelines are identified and engaged in the implementation process.

-

Environmental readiness assessment for implementation is conducted for its impact on guideline uptake.

-

Barriers and facilitators to use of the guideline are assessed and addressed on an ongoing basis.

-

Interventions are selected that consider barriers and facilitators within the organization.

-

Guideline use is systematically monitored and sustained.

-

Action plans for sustainability of practice changes are developed, reviewed, and updated on a regular basis.

-

Evaluation of the impacts of guideline use is embedded into the process.

-

Adequate resources to complete the activities related to all aspects of guideline implementation are made available.

These elements ensure a systematic implementation process and are used by senior administration BPSO sponsors, BPSO Leads, Champion Leaders, BPG Champions, and BPG Leaders.

Ensuring BPSO success

There are a number of features delineated as expectations that make the BPSO Designation a most effective knowledge translation (KT) strategy to bring evidence to sustained daily use in practice. These are recognized as strategies “that work” and continue to be espoused in the literature (Melnyk, 2014). They have been honed over the last 15 years of the BPSO Designation based on implementation science research and experiential knowledge and are included in the BPSO Agreement. They represent the following elements: development of an infrastructure, capacity building, implementation, dissemination, monitoring and reporting progress, evaluation, as well as audit and feedback. Each is discussed next.

Infrastructure

The BPSO Agreement reinforces that it is important to create an infrastructure. It involves individuals in key roles; defined reporting relationships; linkages to committees that oversee and make strategic decisions about BPG implementation and resource allocation, and to existing structures that make and implement operational decisions to support guideline implementation (RNAO, 2017b). Many of these elements are supported by Grol et al. (2013).

The BPSO infrastructure must not be separate from the ongoing business of the organization and must be tightly connected to existing groups focused on professional practice and quality/risk management, such that the BPSO and guideline implementation are part of the organization’s mainstream operations. Moreover, and as indicated previously, organizations are advised to leverage their mission, vision, strategic directions, and quality-improvement activities to align with the BPSO goals (Bajnok et al., 2015). These are also characteristics recommended by Melnyk (2014).

In exploring the roles of system and organizational leadership in evidence-based intervention, Aarons et al. (2016) demonstrated strong relationships between transformational leadership and visible support, and success in evidence-based intervention. In addition, the authors noted the importance of alignment, in support for evidence-based practice (EBP), amongst leadership at the clinical, middle management, and executive levels. This important point is supported by many who have studied success factors in EBP implementation (Aarons et al., 2016; Bajnok et al., 2015; Chambers et al., 2013; Gifford et al., 2011; Higuchi et al., 2017; Melnyk, 2014; Rogers, 2003; Stetler et al., 2014). The BPSO Host and Direct Models creates clear expectations for strong links between the support and mentoring of leadership at the executive nurse level—and indeed all levels in the organization—in order to fuel success in initiating and sustaining EBP.

Key deliverables in relation to the infrastructure expectations of a BPSO Direct include:

-

Formation of a steering committee consisting of key stakeholders fully engaged with the BPSO work, including the BPSO Sponsor, BPSO Lead, Champion Leaders, BPG Leaders and Champions, and other stakeholders who will be impacted by, or who can influence, its success

-

Identification of a BPSO Sponsor, who is usually the Chief Nurse Executive or equivalent role, who champions the BPSO Designation within the senior team and organization and supports the BPSO Lead

-

Appointment of a BPSO Lead who is able to devote at least half of her work time to lead the BPSO, manage deliverables, carry out related activities, and be the organization’s link to RNAO (in some cases, depending on the organizational context, the BPSO Sponsor may also act as the BPSO Lead)

-

Creation of BPG implementation teams and BPG Leaders who lead the implementation team; become experts on the topic and the BPG; and work with the BPSO Lead to develop and monitor implementation strategies from practice change, to policy reviews and revision, to education activities for direct-care nurses and others

-

Development of Champions in all roles who work directly with their peers in knowledge broker, ambassador, teaching, mentoring, and role-modeling activities

-

Establishment of key reporting and decision-making processes, as depicted in a model describing their BPSO infrastructure

Years of working with BPSOs have demonstrated that when these structures are in place, the BPSO Designation is valued, visible, integrated, and aligned with organizational priorities, achieved in a timely manner, and sustained for the long term.

Capacity building

It is critical that education be provided to staff in all roles so they can lead and support the practice changes resulting from the BPG implementation (Melnyk, 2017). The RNAO BPSO Direct Agreement stipulates several capacity-building requirements that must be undertaken by staff.

Capacity-building activities generally begin with the BPSO Orientation Program, to which each BPSO must send representatives as stipulated in the BPSO Agreement, including the Chief Nurse as the BPSO sponsor, BPSO Lead, and Champion Leaders. Other and ongoing capacity-building activities include: development and maintenance of a cohort of Best Practice Champions; attendance at RNAO’s Clinical BPG Institute; involvement in monthly virtual knowledge-exchanges sessions for qualifying BPSOs and quarterly sessions for Designate BPSOs; and attendance at the annual in-person BPSO Knowledge Exchange Symposium. The attention to ensuring key leaders in the BPSO have a strong EBP knowledge base, an understanding of RNAO’s BPGs and the BPSO, is well founded in the literature. Implementation science experts have reached a strong consensus that an understanding of evidence-based practice (Bajnok et al., 2015; Grinspun et al., 2014; Melnyk, 2017; Melnyk et al., 2014; Stetler et al., 2014), and in particular of the science of creating and sustaining practice (Gallagher-Ford, Buck, & Melnyk, 2014; Grol et al., 2013; Higuchi et al., 2017) change, is imperative if BPGs are to be implemented by nursing and other staff.

BPSO orientation

The BPSO Orientation is a 2-day program scheduled for BPSOs in Ontario, or a 5-day program scheduled for sites outside Ontario. For Ontario sites, the 2-day session is scheduled as a launch, with engagement of Ontario’s Chief Nurse, other members of the government, the RNAO CEO, and the RNAO BPG Team, including the BPSO Coaches. The agenda includes details of the RNAO BPG Program and the BPSO Designation, as well as the steps to get started as a BPSO. It also provides for interaction amongst BPSOs and an opportunity for each BPSO to showcase its site, the BPGs selected, and its overall plans.

This helps to build a foundation for the peer networks all BPSOs become a part of and begins to cultivate the collective identity of the new BPSO cohort as a member of the global BPSO community (see Chapter 1 for an introduction and discussion of the concept of collective identity). Following this, the BPG Institute (outlined in detail in Chapter 4) serves as an orientation for the BPSOs who send representatives to the Institute according to their organization size as stipulated in the BPSO Agreement. This 5-day program provides specific knowledge and application sessions based on implementation science to help in BPG implementation and related deliverables expected of BPSOs.

For international BPSOs, there are some differences that arise because of distance and the travel and scheduling requirements for RNAO International BPSO Coaches, who lead the orientation sessions in international jurisdictions. International BPSOs must send representatives to the initial BPSO Orientation Program, which is a 5-day BPSO launch and education session hosted by the BPSO site. Since the orientation is on site and scheduled for one or two new BPSOs at a time, the organizations send substantial numbers of staff to this session, generating much energy and imparting new knowledge and skills on a large scale that fuel a successful start-up. In some cases, like in the Latin- American BPSO consortium described in Chapter 15, two countries—Chile and Colombia—joined together for their BPSO Orientation Program, creating a strong and unique bonding that has characterized that region since.

The BPSO launch portion of this orientation serves as an introduction of the program to key government, nursing, and other health professional stakeholders in the country or jurisdiction, and showcases the organization and its goals in becoming a BPSO. In addition, it begins to create a strong sense of collective identity amongst all attendees about their profile as a BPSO and membership in the global BPSO network. This identity is demonstrated, for example, in proud displays of the BPSO logo on nursing units, on written documents (including organizational letterhead), Champion buttons, and uniforms. The logo is country-specific, and in Figure 6.1 the logos for China, Colombia, and Qatar are displayed as examples.

The BPSO Orientation Program and the BPG Learning Institutes are identified as training programs in RNAO’s Training of Trainers (TOT) Model in which the RNAO BPSO International Coaches, as Master Trainers, train the BPSO Sponsors, BPSO Leads, and Champion Leaders, who in turn train Champions and BPG Leaders in 1- to 2-day workshops in their jurisdictions.

The BPSO Orientation Program and the BPG Learning Institutes are identified as training programs in RNAO’s Training of Trainers (TOT) Model in which the RNAO BPSO International Coaches, as Master Trainers, train the BPSO Sponsors, BPSO Leads, and Champion Leaders, who in turn train Champions and BPG Leaders in 1- to 2-day workshops in their jurisdictions.

A key factor in BPG uptake in the BPSOs is the focus on the process of change or adoption of the innovation (Grol et al., 2013) and the transition process (Bridges, 1991) or becoming an evidence-based culture. BPSO Sponsors, BPSO Leads, and Champion Leaders learn how to use the change process throughout all aspects of the adoption cycle (Rogers, 2003). Different theories of change are incorporated in their education, including:

-

Rogers’ (2003) insights on the rate of adoption of change and the categories of adopters

-

Conner (2006), who recognizes eight stages of change beginning with first contact and awareness and ending with institutionalization and internalization to secure the new practices

-

Kotter’s (2012) eight-step change process starting with the burning platform, which helps change agents align the change to organizational realities and create the motivation for change

-

The ADKAR model (Hiatt, 2006) which highlights the role of education in change

-

Heath & Heath (2010), who focus on practical ways of initiating and sustaining change

In addition, the RNAO Toolkit, reinforcing Lewin’s change theory, recognizes the importance of psychological safety (Schein, 1996) as clinicians try out new evidence-based practices.

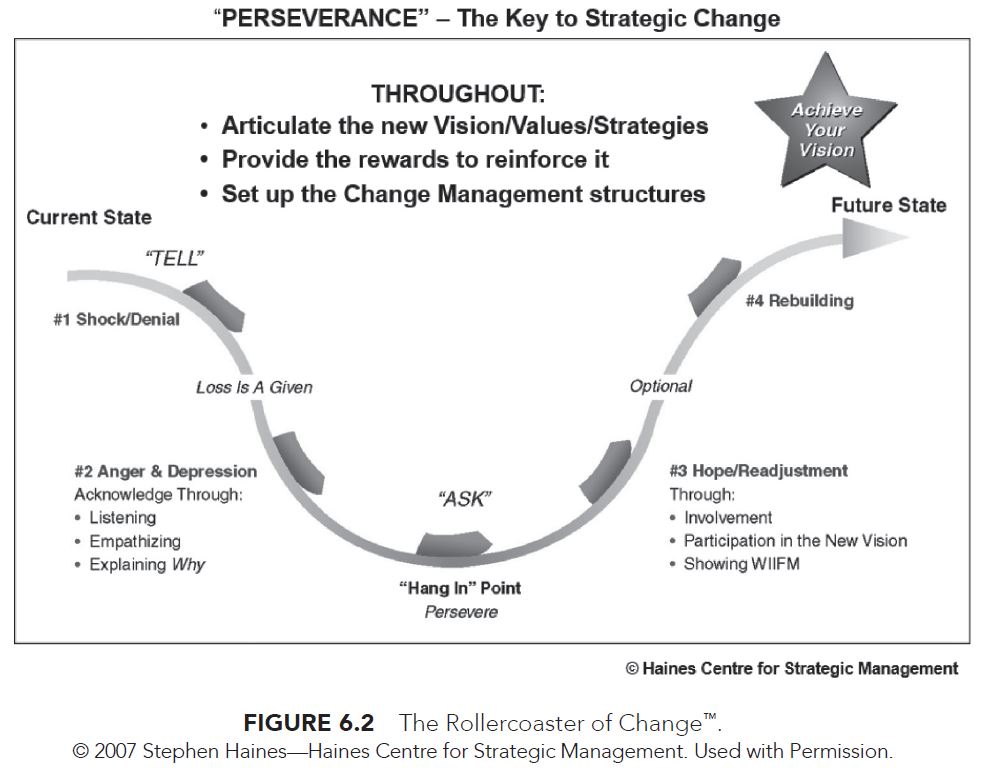

The BPSO Orientation Program and BPG Learning Institute portray change using Haines’s (2005) work, which depicts the ups and downs of change as akin to a rollercoaster ride, and indeed multiple rollercoasters and waves of change, in the nonlinear process of adoption of best practices through transition (Bridges, 1991). The rollercoaster of change shown in Figure 6.2 becomes very symbolic for BPSO Leaders around the world both as they measure their own reactions to change compared to their colleagues, and as they gain knowledge about the predictable responses to change and the need for perseverance (Haines, 2005). This content and the related methodology used in discussion and application, like much of the common content in these orientation sessions, begin to shape the collective identity of BPSOs as members of a global EBP movement.

The BPSO Orientation Program and BPG Learning Institute portray change using Haines’s (2005) work, which depicts the ups and downs of change as akin to a rollercoaster ride, and indeed multiple rollercoasters and waves of change, in the nonlinear process of adoption of best practices through transition (Bridges, 1991). The rollercoaster of change shown in Figure 6.2 becomes very symbolic for BPSO Leaders around the world both as they measure their own reactions to change compared to their colleagues, and as they gain knowledge about the predictable responses to change and the need for perseverance (Haines, 2005). This content and the related methodology used in discussion and application, like much of the common content in these orientation sessions, begin to shape the collective identity of BPSOs as members of a global EBP movement.

Champions

RNAO requires in its BPSO Direct and BPSO Host Agreements that BPSOs develop 15% of their nursing staff as Best Practice Champions, who will provide the inspiration and motivation for the change (RNAO, 2017b). This is consistent with diffusion theory that defines critical mass as the degree of momentum or energy needed to initiate and sustain a change (Rogers, 2003). The recommended number required to reach critical mass according to Rogers (2003) is 10% to 30% of the target group. RNAO’s selection of 15% reflects the combined estimations of innovators (2.5%) and early adopters (13.5%) when adopters are plotted on the adoption curve. Our experience throughout 15 years has been that this number, when maintained and in most cases exceeded, does sustain the momentum for BPG uptake.

The Champion development process begins with staff members being selected by their unit team lead/ manager or volunteering to take on this role. They become Champions by participating in a 1-day, in-person workshop; a virtual learning series; or via a self-directed eLearning program. By becoming a Champion, those involved commit to facilitating and leading BPG implementation amongst their peers. Other healthcare professionals are encouraged to become Champions, and hundreds have been prepared through the RNAO Champion program. In addition, there are now thousands of nurses, nursing students, support staff, and more recently members of the public, who have become part of the RNAO Best Practice Champion Network.

BPG Clinical Learning Institute

RNAO’s Clinical BPG Institute, now in its 16th year, provides an opportunity for nurses and other healthcare professionals to gain knowledge, understanding, and opportunities to apply elements of the Toolkit (RNAO, 2012) to an action plan for guideline implementation. Use of a multifaceted action plan was a key recommendation of Higuchi et al. (2017), based on a study of eight pioneer BPSOs.

Participants come to the BPG Institute with an idea of an evidence-based clinical innovation they want to implement and leave with a clear plan of how to bring knowledge to action. Both the Champion’s workshop and the BPG Learning Institute are based on the RNAO Implementation Toolkit (2012).

BPSO knowledge exchange sessions

Knowledge exchange sessions with peer BPSOs provide an opportunity to learn from each other’s successes and challenges. BPSOs are required to present regular, comprehensive updates to their peers for information, feedback, and problem-solving. The annual BPSO Knowledge Exchange Symposium is hosted by RNAO for all BPSOs, including those who have been designated and those in the pre-designation period. The goals of the Symposium are knowledge exchange, collaboration, celebration, and networking. BPSOs share lessons learned, Designated BPSOs mentor new BPSOs, and implementation science experts bring new knowledge to the group. Leaders from all BPSOs are expected to attend and present their progress during networking sessions that are a highlight of the event.

Coaching and support

Engagement with a BPSO Coach is another key strategy that is embedded in the BPSO Designation. Harvey et al. (2002) emphasized the role of facilitation while leading practice change and introduced the role of external facilitators who utilize an outreach model to work with organizations, providing advice, networking, and support to help them establish the required practice changes. Pre-Designation BPSOs have an assigned experienced implementation expert from RNAO (BPSO Coach) whom they must meet within the first 3 months of becoming a BPSO and maintain regular contact with over the 3-year period. The role of the Coach has recently expanded to include a site visit for the purposes of observing “on the ground” implementation and evaluation. Coaches provide consultation, role modeling, referral to key resources, and early identification of challenges to achieving BPSO Designation.

Engagement with a BPSO Coach is another key strategy that is embedded in the BPSO Designation. Harvey et al. (2002) emphasized the role of facilitation while leading practice change and introduced the role of external facilitators who utilize an outreach model to work with organizations, providing advice, networking, and support to help them establish the required practice changes. Pre-Designation BPSOs have an assigned experienced implementation expert from RNAO (BPSO Coach) whom they must meet within the first 3 months of becoming a BPSO and maintain regular contact with over the 3-year period. The role of the Coach has recently expanded to include a site visit for the purposes of observing “on the ground” implementation and evaluation. Coaches provide consultation, role modeling, referral to key resources, and early identification of challenges to achieving BPSO Designation.

Sustained implementation

During the 3-year pre-designation period, Canadian BPSOs are required to implement a minimum of five clinical BPGs (three across the entire organization), and international BPSOs are required to implement a minimum of three (one across the entire organization). This difference in requirement acknowledges the fact that Canadian nurses have had ready access to the RNAO BPG Program and its resources since its inception; it also recognizes that there may be differences in context in international settings related to EBP. BPSOs must determine where (units, programs, teams) the implementation will take place and utilize the practice recommendations to direct the clinical interventions. The education recommendations are used to ensure staff have the knowledge and skill to carry out the clinical interventions, and the organization/policy recommendations to support sustainment of the practice change. These requirements ensure that the practice changes “stick” because of knowledgeable and committed staff, and that the necessary structures and processes are in place to embed the new practices.

All BPSOs are required to develop a sustainability plan focused on organizational structures, processes, and roles and to keep the plan updated to share with RNAO through the required reporting. These elements are strongly supported by Chambers et al. (2013) and Maher et al. (2010) in their discussions of sustainability as part of implementation of EBP. The partnership amongst BPSOs and RNAO provides many opportunities for organizations to receive and give feedback. This enables RNAO and the BPSOs to adapt and modify their approaches based on outcomes, changes in evidence, and changes in context both at the organizational and the system levels. As reinforced by Chambers et al. (2013) in “The Dynamic Sustainability Framework,” sustained practice is not a static concept, and there is high recognition for sustainment that evolves over time based on current best evidence.

Dissemination

Given the value of reflection and regular progress reviews, BPSOs are required in their formal agreement to consolidate their work and share it in a public way. This is achieved through professional presentations at local, provincial, national, and/or international conferences; sharing the resources they develop on the RNAO website; or by participating as faculty for RNAO professional development offerings. RNAO also expects that the BPSO will feature its BPSO activities on its organization’s website, and more recently it has become a requirement to establish a social media presence through which BPSO work can be disseminated. Finally, development and submission of manuscripts related to the BPSO Designation process and outcomes for publication in peer-reviewed journals is an expectation during the predesignation period and continues post-BPSO Designation. This deliverable contributes to capacity building within BPSOs; positions the BPSO and its leaders locally and beyond, thus strengthening their status in their organizations and communities; facilitates emerging clinical and nursing knowledge for wide consumption; and demonstrates the ever-expanding knowledge base of the nursing profession. BPSOs share their progress on this deliverable in the semi annual or annual report to RNAO.

Monitoring and reporting progress

As a way of monitoring that all deliverables are met—aside from the opportunities afforded through the regular knowledge exchange meetings, in-person Symposiums, and interaction with the BPSO Coaches—predesignate BPSO Directs and Hosts submit a formal written report to RNAO on a semi-annual basis. As previously mentioned, the reporting format is available online through myBPSO and requires an update on all deliverables. For Designated BPSOs, the reporting requirement is an annual submission, with designation renewal every 2 years. For Canadian BPSO Directs, the IABPG Director and Associate Director of Guideline Implementation and Knowledge Transfer, as well as the BPSO Coach, conduct a virtual meeting with the BPSO Lead, Sponsor, and other members of the BPSO team to discuss the report. For international BPSOs and BPSO Hosts, these meetings are led by either the RNAO CEO or the Director of the International Affairs and Best Practice Guidelines Centre, as their identified Coach.

The ARCH Model (Baker, Turner, & Bush, 2015)—which includes Self Assessment, Reinforcement, Correction, and Help with an action plan—is used to guide and focus the discussion, ensure two-way communication, identify and reinforce strengths, and outline plans to address any challenges. Follow-up notes are communicated to the BPSO, including areas to address immediately, and areas to be addressed in the next report. At year end, decisions are made to determine if the BPSO has met the annual deliverables in order to move to the next year. At the end of the 3-year period, a review is conducted to determine whether the deliverables have been met sufficiently to enable designation. There have been situations in which, due to competing priorities, staffing changes, or major organizational restructuring, BPSOs require an extension of 6 months to a year in order to achieve the deliverables required for designation. In all cases, these BPSOs have been successful within the extended qualifying timeframe.

Evaluation

With the establishment of NQuIRE, the evaluation and monitoring deliverable has become robust and consistent across BPSOs (Grinspun et al., 2015). From the outset, BPSOs are expected to collect baseline data for key human resource structure indicators and for process and outcome indicators

related to the BPGs they are implementing. Service BPSOs submit monthly data on a quarterly basis to NQuIRE and share their results in their regular written reports to RNAO (Grinspun et al., 2015). Academic BPSOs do not yet submit data to NQuIRE. However, they identify, measure, and report on key indicators such as: BPGs’ influence on the overall curriculum, course objectives and content; teaching methodology; student knowledge; and student practice skills.

BPSO Hosts

BPSO Host organizations have specific deliverables they must meet as part of the signed Agreement with the RNAO Host Organization (RNAO, 2017b). These deliverables focus on actions and accomplishments necessary in their role of recruiting, initiating, and overseeing a cadre of BPSO Directs in their jurisdiction, all of whom must have a signed BPSO Direct Agreement with the Host. BPSO Hosts are supported and monitored by RNAO and are divided between RNAO’s CEO and the IABPG Director. The Latin America BPSO Consortium (composed of BPSO Directs in Chile, Colombia, and Portugal, as well as BPSO Hosts in Chile, Peru, and Spain.) also report to RNAO’s CEO, who is fluent in Spanish. RNAO’s focus in coaching and monitoring is on the BPSO Host itself and its role in the oversight of its BPSO Directs. RNAO’s focus extends to those BPSO Directs only to determine the BPSO Host’s progress and its ability to meet the deliverables.

Audit and feedback

In addition to the numerous monitoring strategies used, and based on the views that observing BPSOs in their own context and providing direct feedback on their performance as assessed against the standards (Ivers et al., 2012) is conducive to enhanced behaviours, RNAO conducts a formal, annual, onsite audit of its BPSO Directs and the BPSO Hosts. The value of audit and feedback is reinforced by Ivers et al. (2014), based on the results of an in-depth analysis of a systematic review of 140 studies in which they examined effects on professional practice when audit and feedback were included as a critical aspect of the care processes. Ivers and colleagues (2014) concluded that while there was variation in impact on professionals and patients, audit and feedback were effective in situations in which there was a high learning curve involved in uptake of the new practices and when the feedback was provided by a supervisor or colleague, verbally and in writing, with intention to follow up and an action plan. Audit and feedback were also more effective when targeted to nonphysicians.

Our audit and feedback process meets the above criteria and has become an effective way for us to determine the fidelity of the BPSOs in relation to the program requirements outlined in the BPSO Agreements. The intent is to help BPSO Directs and BPSO Hosts not only to modify their behaviours when they are not meeting expectations, but also to learn what they are doing well in order to sustain these actions. Consistent with the findings of Ivers et al. (2014), the BPSO Coaches are involved in the audit, and they provide verbal and written feedback to the BPSO about their progress. Specific audit tools, aligned with the relevant requirements, have been developed for BPSO Hosts, and academic and service BPSO Directs, and serve as guides to the auditors and as teaching tools during feedback sessions. These sessions also include a focus on specific action plans to be addressed and the timeframe. The audit and feedback processes are outlined in more detail in Chapter 12, RNAO’s Global Spread of BPGs: The BPSO Designation Sustainability and Fidelity.

Summary of BPSO requirements

These key deliverables required of qualifying and Designated BPSOs are evidence-based, achievable, and, over a 3-year period and beyond, create the momentum and the milieu needed for sustainment and expansion of evidence-based practice changes. They are summarized here:

-

Develop a BPSO infrastructure with structures, people, and processes:

-

Build capacity throughout the organization related to the clinical practice change and an enhanced understanding of knowledge-translation methodologies

-

Participate in regular knowledge exchange sessions with other BPSOs as part of a peer network

-

Act as a mentor or be mentored by others

-

Establish and maintain an informed and engaged cadre of Champions

-

Utilize a systematic approach to implementation focused on practice change, education of clinicians and support staff, and embedding the new practices in organizational structures and processes:

-

Consult with the RNAO BPSO Coach to assist with challenges and strategies

-

Develop clear plans for evaluation, including submission of data to NQuIRE, with a focus on structure, process, and outcome indicators and how the results of this data will be shared with staff

-

Disseminate results through professional presentations and scholarly publications

-

Provide regular reports through myBPSO to RNAO focused on key deliverables

The BPSOs consistently identify these requirements and deliverables, in particular the formal partnership and resources and supports from RNAO, as key to their success (RNAO, 2015).

They are all elements of implementation science, and each has been used in some program of evidence-based practice development. The BPSO Designation has bundled this entire set of implementation science practices and principles into one comprehensive knowledge-translation initiative that has achieved proven results and created a collective identity the world over.

As discussed in Chapter 1, Transforming Nursing Through Knowledge: The Conceptual and Programmatic Underpinnings of RNAO’s BPG Program, BPSOs have an interactive and shared journey, with a clear orientation of their action as well as the opportunities and constraints in which their action takes place. They find motivation amongst themselves and in one another. They recognize that they share certain orientations in common and on that basis decide to act together. BPSOs have active relationships amongst themselves and are intellectually and emotionally invested in their individual and collective success.

As discussed in Chapter 1, Transforming Nursing Through Knowledge: The Conceptual and Programmatic Underpinnings of RNAO’s BPG Program, BPSOs have an interactive and shared journey, with a clear orientation of their action as well as the opportunities and constraints in which their action takes place. They find motivation amongst themselves and in one another. They recognize that they share certain orientations in common and on that basis decide to act together. BPSOs have active relationships amongst themselves and are intellectually and emotionally invested in their individual and collective success.

RNAO’s commitments

The BPSO Designation is a partnership between RNAO and the BPSO, mobilized by the collective identity and goals of better outcomes for patients, nurses, other providers, organizations, and the health system as a whole. The partnership reinforces full engagement of BPSOs around the world in all aspects of the designation and espouses the philosophy of sustained capacity building. RNAO’s commitments to the BPSO Directs and BPSO Hosts are seen as critical to their ability to meet the deliverables, establish a culture of evidence-based practice, and contribute to sustained capacity building. They include:

-

Rigorously developed evidence-based guidelines and implementation resources, all freely available for download on the RNAO website

-

Access to technology-enabled implementation resources such as the RNAO BPG app and the evidence-based Nursing Order Sets

-

NQuIRE, RNAO’s comprehensive indicator database system to measure BPG impact

-

Support for opportunities to become a BPSO and be part of a formal BPSO network

-

BPSO consultation and coaching from knowledge transfer, guideline development, and evaluation experts

-

Provision of comprehensive and relevant capacity-building, networking, and information-sharing resources, and professional development opportunities

-

Facilitation of knowledge-transfer forums such as the virtual BPSO Community of Practice, annual BPSO Knowledge Exchange Symposium, and regular BPSO Knowledge Exchange meetings

-

RNAO’s technology-enabled reporting system, myBPSO

-

Review of required BPSO reports submitted through myBPSO, and provision of timely interactive feedback

-

Promotion of BPSOs and their work through media features, opportunities for publication, and local and international mentoring connections

-

Opportunities to mentor other BPSOs and to be part of the Certified BPSO Orientation Trainer network and the Certified Trained BPSO Auditor network (see details in Chapter 12)

BPSO success factors

The BPSO Designation is internationally renowned and has been a resounding success in demonstrating the uptake and sustained use of Best Practice Guidelines. The BPSO Designation’s strategic approach has served to trigger the development of evidence-based cultures, improve patient care, and enrich the professional practice of nurses and other healthcare providers. At the time of writing, there were 7 BPSO Hosts composed of 125 BPSOs Direct that represent over 550 healthcare organizations and academic institutions in 12 countries and 5 continents.

Conclusion and future considerations

While this initiative has incubated, RNAO and all the BPSOs and BPSO Hosts remain vigilant in ensuring nothing interferes with gains made. They work continuously in partnership to reduce the knowledge-to-practice gap and to extend the BPSO Designation in current jurisdictions and scale out to new ones. The future will see more formalized approaches to sustained capacity building, including more Champion Leaders, BPG Leaders, Mentors, and Coaches identified from BPSO Hosts and BPSO Directs around the world. Plans are in place to support the rapid growth of BPSO Directs in Canada, China, and Eastern Europe; as well as to launch and develop BPSO Hosts in Canada, Chile, China, Peru, and several European countries.

RNAO’s infrastructure; credibility as a professional association that speaks out for health and for nursing; and its broad practice, education, administration, research, and policy networks fuel its ability to sustain and grow the BPSO Designation. This crucial global initiative of KT is making it possible for healthcare organizations to establish evidence-based cultures; for nurses passionate about evidence-based care to thrive and lead knowledge-based change; and for clients to take comfort in knowing that the best evidence is being used to inform their care. The BPSO Direct and BPSO Host Models have been tested over 15 and 6 years respectively and have demonstrated that the BPSO Designation model fits a variety of global contexts.

As outlined in this chapter, RNAO’s groundbreaking meso- and macro-level KT strategy, the BPSO Designation, is successful largely because of a set of requirements embodied in a signed formal agreement between the BPSO and RNAO. The Agreement ensures that organizations are clear about the expectations they must achieve and what supports and resources RNAO commits to provide. The explicit understanding is that with this type of partnership, organizations will be assured of achieving a culture of evidence-based practice and uptake of multiple BPGs. The RNAO BPSO Designation provides a proven model that brings knowledge to action through multiple interrelated strategies and evidence-based resources. This leads to more rapid practice change based on best evidence, and results in better patient and organizational outcomes. The world’s patients deserve nothing less.

Key messages

-

A combination of principles and practices derived from implementation science literature, when applied at the organizational level, provides success in closing the knowledge-to-practice gap in healthcare.

-

Leadership in all roles is critical to initiate and sustain development of an evidence-based practice culture.

-

Understanding and applying change theory is a critical aspect of initiating and fostering sustained BPG uptake.

-

Attention to all aspects of evidence-based practice—from rigorous guideline development to capacity building focused on both clinical knowledge and implementation science principles, evaluation, and sustainment—is necessary to achieve results.

-

Organizations aiming to create an evidence-based culture benefit from working closely with both experts and peers striving for similar goals.

-

There is a greater likelihood of success when the goal to achieve an evidence-based culture is aligned with the organizational vision, mission, and strategic priorities.

-

Global uptake of evidence-based practice in nursing enables consistent approaches to care, facilitates intra- and inter-professional communication and collaboration, enhances opportunities for research, and ultimately strengthens the profession and its impact on clients.

Irmajean Bajnok, PhD, MScN, BScN, RN, is the former Director of the International Affairs and Best Practice Guidelines (IABPG) Centre at the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (RNAO).

Doris Grinspun, PhD, MSN, BScN, RN, LLD(hon), Dr(hc), O.ONT, is the CEO of RNAO.

Heather McConnell, MA(Ed), BScN, RN, is Associate Director, Guideline Implementation and Knowledge Transfer, at RNAO.

Barbara Davies, PhD, RN, FCAHS, is a retired professor from the University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Click here to purchase Transforming Nursing Through Knowledge.

Appendix A: Steps to becoming a Best Practice Spotlight Organization (BPSO)

References

Aarons, G., Green, A., Trott, E., Willging, C., Torres, E., Ehrhart, M., . . . Roesch, S. (2016). The roles of system and organizational leadership in system-wide evidence-based intervention sustainment: A mixed-methods study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 43, 991–1008.

Albornos-Munoz, L., González-María, E., & Moreno-Casbas, T. (2015). Best Practice Guidelines implementation in Spain: Best practice spotlight organizations. MedUNAB, 17(3), 163–169.

Bajnok, I., Grinspun, D., Lloyd, M., & McConnell, H. (2015). Leading quality improvement through Best Practice Guideline development, implementation, and measurement science. Med UNAB, 17(3), 155–162.

Baker, S. D., Turner, G., & Bush, S. C. (2015, November). ARCH: A guidance model for providing effective feedback to learners [Education column]. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Retrieved from http://www.stfm.org/NewsJournals/EducationColumns/

November2015EducationColumn

Bridges, W. (1991). Managing transitions: Making the most of change. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8, 117. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-117

Conner, D. (2006). Managing at the speed of change: How resilient managers succeed and prosper where others fail. New York, NY: Random House Publishing Group.

Di Costanzo, M. (2013). Becoming a BPSO. Registered Nurse Journal, 25(2), 12–26.

Gallagher-Ford, L. (2014). Implementing and sustaining EBP in real world healthcare settings: A leader’s role in creating a strong context for EBP. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 11(1), 72–74.

Gallagher-Ford, L., Buck, J., & Melnyk, B. M. (2014). Leadership strategies and evidence-based practice competencies to sustain a culture and environment that supports best practice. In B. M. Melnyk & E. Fineout-Overholt (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (3rd ed.) (pp. 235–247). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

Gifford, W., Davies, B., Tourangeau, A., & Lefebre, N. (2011). Developing team leadership to facilitate guideline utilization: Planning and evaluating a three-month intervention strategy. Journal of Nursing Management, 19, 121–132.

Graham, I. D., Logan, J., Harrison, M. B., Straus, S. E., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., . . . Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13–24.

Grinspun, D. (2011). Guias de practica clinica y entorno laboral basados en la evidencia elaboradas por la Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) (Evidence based clinical practice and work environment guidelines prepared by the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario). Enfermeria Clinica (Clinical Nursing), 21(1), 1–2.

Grinspun, D., Lloyd, M., Xiao, S., & Bajnok, I. (2015). Measuring quality of evidence-based care: NQuIRE-Nursing Quality Indicators for Reporting and Evaluation data-system. MedUNAB, 17(3), 170–175.

Grinspun, D., Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2014). Advancing optimal care with rigorously developed clinical practice guidelines and evidence-based recommendations. In B. M. Melnyk & E. Fineout-Overholt (Eds.), Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (3rd ed.) (pp. 182–201). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

Grinspun, D., Virani, T., & Bajnok, I. (2002). Nursing Best Practice Guidelines: The Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario project. Hospital Quarterly, 5(2), 56–60.

Grol, R., Wensing, M., Eccles, M., & Davis, D. (2013). Improving patient care: The implementation of change in health care (2nd ed.). London, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Haines, S. (2005). Leading strategic change. San Diego, CA: Systems Thinking Press.

Haines, S. (2007). The natural cycles of life and change. Retrieved from http://hainescentre.com/rollercoaster/

Harvey, G., Loftus-Hills, A., Rycroft-Malone, J., Titchen, A. I., Kitson, A., McCormack, B., . . . Seers, K. (2002). Getting evidence into practice: The role and function of facilitation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(6), 577–588.

Health Council of Canada. (2012). Understanding clinical practice guidelines: A video series primer. Retrieved from https://healthcouncilcanada.ca/files/CPG_Backgrounder_EN.pdf.pdf

Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2010). Switch: How to change things when change is hard. New York, NY: Random House.

Hiatt, J. M. (2006). ADKAR: A model for change in business, government and our community. Loveland, CO, U.S. Prosci Research.

Higuchi, K., Davies, B., & Ploeg, J. (2017). Sustaining guideline implementation: A multisite perspective on activities, challenges and supports. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 1–12. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13770

Higuchi, K., Downey, A., Davies, B., Bajnok, I., & Waggott, M. (2013). Using the NHS sustainability framework to understand the activities and resource implications of Canadian nursing guideline early adopters. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(11–12), 1706–1716.

Ivers, N., Jamtvedt, G., Flottorp, S., Young, J. M., Odgaard-Jensen, J., French, S. D., . . . Oxman A. D. (2012). Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, CD000259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3

Ivers, N., Sales, A., Colquhoun, H., Michie, S., Foy, R., Francis, J. J., . . . Grimshaw, J. M. (2014). No more ‘business as usual’ with audit and feedback interventions: Towards an agenda for a reinvigorated intervention. Implementation Science, 9, 14. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-14

Kirschling, J., & Erickson, J. (2010). The STTI practice academe collaborative partnership award: Honoring innovation, partnership and excellence. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(3), 286–294.

Kotter, J. P. (2012). Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Maher, L., Gustafson, D., & Evans, A. (2010). NHS Sustainability Model. Retrieved from http://www.institute.nhs.uk/ sustainability

Melnyk, B. M. (2014). Building cultures and environments that facilitate clinician behaviour change to evidence-based practice: What works? Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 11(2), 79–80.

Melnyk, B. M. (2017). The difference between what is known and what is done is lethal: Evidence-based practice is a key solution urgently needed. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 14(1), 3–4.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2015). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice (3rd ed).Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

Melnyk, B. M., Gallagher-Ford, L., Koshy, B. K., Troseth, M., Wygarden, E., & Szalacha, L. (2016). A study of chief nurse executives indicates low prioritization of evidence-based practice and shortcomings in hospital performance metrics across the United States. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 13(1), 6–14.

Ploeg, J., Davies, B., Edwards, N., Gifford, W., & Miller, E. P. (2007). Factors influencing BPG implementation: Lessons learned from administrators, nursing staff and project leaders. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 4(4), 210–219.

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). (2012). Toolkit: Implementation of Best Practice Guidelines (2nd ed.).Toronto, ON: Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario.

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). (2015). 2014–2015 Best Practice Spotlight Organization impact survey: Summary of survey results. Retrieved from http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/FINAL_RNAO-BPSO_Impact_Survey_from_Printer.pdf

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). (2017a). Best Practice Spotlight Organizations (BPSO). Retrieved from http://rnao.ca/bpg/bpso

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (2017b). RNAO Best Practice Spotlight Organization (BPSO). Retrieved from http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/RNAOBPSOFactSheetApril2017.pdf

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Schein, E. H. (1996). Kurt Lewin’s change theory in the field and in the classroom: Notes toward a model of managed learning. Systems Practice and Action Research, 9(1), 27–47.

Stetler, C. B., Richie, J. A., Rycroft-Malone, J., & Charns, M. P. (2014). Leadership for evidence-based practice: Strategic and functional behaviour for institutionalizing EBP. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 11(4), 219–226.

Straus, S., Tetroe, J., & Graham, I. D. (Eds). (2013). Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice (2nd ed.) Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Nurses and midwifes: A vital resource for health. European compendium of good practices in nursing and midwifery towards Health 2020 goals. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/287356/Nurses-midwives-Vital-Resource-Health-Compendium.pdf

Demonstrate capacity to engage organizations in their jurisdiction to become BPSO Directs with them

Request and review applications through a request-for-proposal process

Formalize relationships with selected organizations through a BPSO Agreement

Provide support to their BPSO Directs to achieve outcomes

Monitor the outcomes achieved

Report to RNAO through myBPSO, as a BPSO Host and on behalf of all its BPSO Direct organizations

Measure and report on outcomes

Demonstrate capacity to engage organizations in their jurisdiction to become BPSO Directs with them

Request and review applications through a request-for-proposal process

Formalize relationships with selected organizations through a BPSO Agreement

Provide support to their BPSO Directs to achieve outcomes

Monitor the outcomes achieved

Report to RNAO through myBPSO, as a BPSO Host and on behalf of all its BPSO Direct organizations

Measure and report on outcomes

Demonstrate capacity to engage organizations in their jurisdiction to become BPSO Directs with them

Request and review applications through a request-for-proposal process

Formalize relationships with selected organizations through a BPSO Agreement

Provide support to their BPSO Directs to achieve outcomes

Monitor the outcomes achieved

Report to RNAO through myBPSO, as a BPSO Host and on behalf of all its BPSO Direct organizations

Measure and report on outcomes