This chapter from Building a Culture of Ownership in Healthcare, a Sigma book, explains why a culture that relies on hierarchical accountability for performance management will inevitably underperform.

Chapter goals

- Describe the three levels of the accountability continuum, what you can and cannot hold people accountable for, and the downside of fostering a culture of hierarchical accountability.

- Describe six reasons why a culture that relies on hierarchical accountability for performance management will inevitably underperform.

- Explain why “the right bus” is the wrong metaphor, and why a much more appropriate metaphor is “the galley ship.”

- Explain why healthcare organizations should transition from a culture of accountability to a culture of ownership.

No one ever changes the oil in a rental car. Most people return the car with a full gas tank because doing so is specified in the contract—they are accountable for it. But no one washes and waxes the car or checks the transmission fluid, because no one feels pride of ownership in a car that belongs to a faceless corporation. When you move from a culture of mere accountability to a culture of ownership, you create a sustainable source of competitive advantage for both recruiting and retaining great people and for earning long-term patient loyalty.

Accountability is doing what

you are supposed to do because someone else expects it of you; it springs from the extrinsic motivation of reward and punishment. The

Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition of accountability is:

Subject to having to report, explain or justify; being answerable, responsible.

An organization that seeks to promote accountability according to this definition will likely end up with a workplace where people do only the tasks that are listed in their job descriptions and never take initiative or go above and beyond the tasks they are being held accountable for. Perhaps worse, there is likely to be a diminished sense of pride in the work itself when it is being done for the expectation of reward or the fear of punishment.

Accountability is extrinsic motivation—being answerable to someone else. Not only can you not hold people accountable for the tasks that really matter, but an excessive focus on accountability also has a real downside. Trying to hold people accountable achieves only a short-term rise in results that quickly deteriorates into another “program of the month” that comes and goes without creating a sustained impact on the cultural DNA of the organization.

Ownership is doing what needs to be done because you expect it of yourself; ownership springs from the intrinsic motivation of pride and engagement. The dictionary definition of ownership is:

The state, relation, or fact of being an owner, which in turn is defined as to have power or mastery over.

A culture in which all employees are encouraged to think like an owner and to have mastery over their work will inevitably outperform an accountability-driven organization in every dimension that truly matters, including employee engagement, productivity, customer service, recruiting and retention success, and profitability.

Leaders need to hold employees accountable for fulfilling the terms of their job descriptions, and for behaving in ways that are consistent with the values and mission of that organization. But in today’s turbulent and hypercompetitive world, that’s not enough to remain competitive, much less to make the now proverbial jump “from good to great.” Employees in great organizations hold themselves and each other to higher standards of expectation for their attitudes and behaviors as well as for their performance at work. They have pride of ownership.

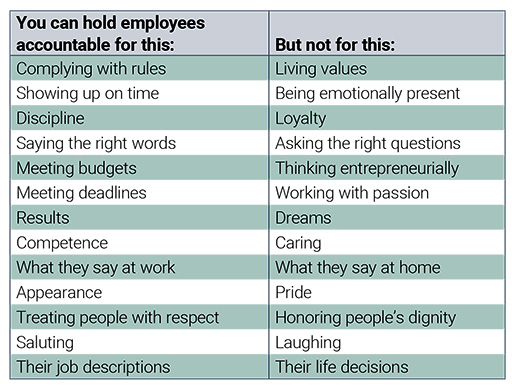

In the course of working with healthcare clients, Joe often hears people say, “We don’t hold each other accountable.” But when he presses the issue, they’re usually not talking about accountability—they’re talking about ownership; they are really saying that people don’t take ownership for their work, their results, and their relationships—and because they are not holding themselves accountable, someone else must do it. So it’s important to distinguish those factors for which employees can be held accountable through managerial discipline or intimidation and those factors for which they cannot be held accountable but which must be accomplished through personal ownership.

The three levels of accountability

Numbers can tell you a lot, but they can’t tell you everything. Counting calories isn’t an effective way to manage your health if your diet is high in arsenic. W. Edwards Deming, the guru of Total Quality Management, said that what gets measured gets done, and he encouraged clients to find ways to quantify every important parameter of the operation. But Deming also said that the most important characteristics of your organization cannot be counted. How does one inventory pride or measure enthusiasm? You can certainly

see these qualities in people’s attitudes and behaviors in the best of organizations, but they are steadfastly resistant to quantification.

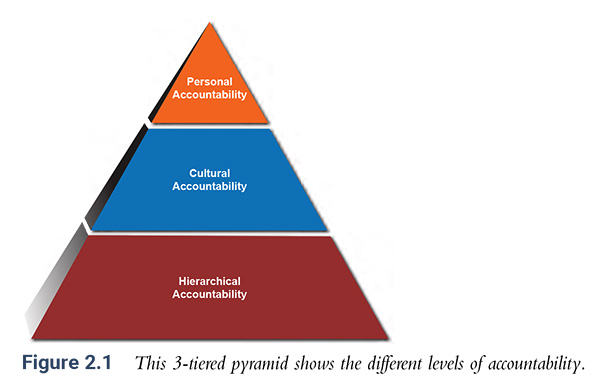

There are three levels of accountability: hierarchical, cultural, and personal. This concept is especially important for leaders in hospitals and other healthcare organizations to understand because you cannot hold people hierarchically accountable for the things that truly matter in the healing professions. You cannot promote caring and compassion, pride and loyalty, or enthusiasm and fellowship by strictly enforcing a code of conduct or by using disciplinary action to hold employees accountable. In that respect, mere accountability establishes a very low bar for performance expectations. The accountability continuum can be seen as a 3-tiered pyramid, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Hierarchical accountability (management)

Hierarchical accountability (management)

At the lowest level,

hierarchical accountability is top-down command-and-control. It’s what people typically mean when they use the word

accountability. It is reward and punishment, looking over people’s shoulders, and holding their feet to the fire (a term that originated from a medieval form of torture).

Hierarchical accountability works especially well in tightly regimented, bureaucratic organizations. The factory worker who misses a quota is docked by the floor manager; the mail clerk who forgets to file a form is sanctioned by the supervisor; a high school math teacher holds students accountable for doing their homework every night by threatening to flunk them at the end of the semester; the teacher in turn is held accountable for students achieving certain scores on standardized tests.

In healthcare contexts, hierarchical accountability is most appropriate for tasks that have significant potential for harm. Employees must be held accountable for administering the proper medications to patients, for completing safety checklists before surgery, and if they are managers for hitting productivity and budgetary targets. They must be held accountable for behaviors that cause harm: theft, bullying, and malicious gossip must have consequences.

Managers often find, to their dismay, that trying to hold people accountable might achieve short-term gains in whatever element is being counted (the word

accountable means “able to be counted”) but, in fairly short order, backsliding begins. A customer service initiative may get off to a good start, with employees being given a script and a happy-face pin and then being held accountable for saying the words. But it soon becomes obvious to patients that some people are simply parroting the script and not speaking from the heart. What the manager is measuring (whether every predetermined word is rattled off in the correct order) is quite different from what patients perceive (a soulless, boring rendition of rules and regulations undertaken from a resentful sense of obligation).

A note from Bob

A note from Bob

As a patient in my own organization, I got out of bed to ambulate soon after surgery. I was in mild pain and had an NG tube still in place. My wife was at my side. If you’ve ever had an NG tube in place, you know it is not comfortable and, of course, doesn’t look good either. In the hallway, I was approached by two nurse managers I know well; I would even consider them friends. I cracked a smile and began having a conversation with them. Then, one manager pulled out her iPad and said she needed to ask some questions about my stay. She began her list of questions. The conversation turned from personal to impersonal quickly. But this was the process we had established to capture data and to assure that our leaders were rounding consistently. If I didn’t like it, what did other patients think?

Soon after this experience, we stopped the scripting and asked each leader to be authentic; to be personable. In a culture of ownership, leaders accept responsibility for patients’ and visitors’ experience. Many stories have been shared in which leaders do extraordinary things to make sure patients are having an exceptional care experience.

Cultural accountability (peers)

Cultural accountability is peer pressure, in the broadest sense of that term. It is far more powerful than hierarchical accountability, for better and worse. In many organizations, cultural accountability exerts a negative pressure on productivity and performance, such as when someone experiences peer pressure against being an overachiever, a quota-buster, or a brown-noser. Attempting to impose hierarchical accountability for customer service excellence in a toxically negative culture requires far more energy than achieving the same outcome with cultural accountability, and is much more likely to fail, because of the inevitable passive-aggressive resistance. Trying to change culture is much harder than merely trying to impose rules, though it is much more likely to achieve a sustained impact.

Perhaps the best example of the power of cultural accountability is the way that enforcement of nonsmoking policies has changed over the years. Hospitals no longer require no-smoking signs in every room, and managers almost never have to discipline employees for sneaking a smoke on the job. Why? Because cultural expectations have changed so profoundly over the past several decades. Anyone lighting a cigarette on an airplane today would not need to be arrested by an air marshal as much as they would need to be rescued from fellow passengers.

Personal accountability (self)

Personal accountability is the highest and best form of accountability. People who accept personal accountability don’t need someone else looking over their shoulders or coworkers pressuring them into behaving in a certain manner—they do it because it’s a reflection of their personal values.

Building a culture of ownership often entails a gradual transition from hierarchical to cultural, and then to personal accountability. Personal accountability, the foundation of a culture of ownership, comes from within, not from above.

At most airlines, flight attendants believe that they’ve completed the job once they’ve parroted the script about seat belts and oxygen masks, whether or not people are actually listening (which, in most cases, they are not). The attendants have passed the test of hierarchical accountability. At Southwest Airlines, on the other hand, flight attendants recognize that the

real job isn’t simply parroting the script—it’s making sure that passengers hear it. When David Holmes presents the words of the script as a rap song or Marty Cobb presents it as a comedy routine, people not only listen, they also give the flight attendant a round of applause. When someone records the performance with a cellphone and the video goes viral, Southwest benefits from millions of dollars’ worth of free advertising.

A culture of ownership provides an unbeatable source of competitive advantage. United Airlines has a culture of accountability; Southwest Airlines has a culture of ownership. Walmart has a culture of accountability; Costco has a culture of ownership. Hertz has a culture of accountability; Enterprise has a culture of ownership. Payless Shoes has a culture of accountability; Zappos has a culture of ownership. In each of these cases, the company with a culture of ownership is winning the competitive battle.

Why accountability isn’t enough

Make no mistake: All three levels of accountability are indispensable in any organization. Accountants must be accountable for getting the math right; nurses must be accountable for giving the proper medications to patients; housekeepers must be accountable for keeping the place clean. The real question is whether they

hold themselves accountable (a culture of ownership) or need to be held accountable by a boss (a culture of accountability). A culture of ownership is not created by economic interest; it springs from emotional commitment. When people feel a sense of ownership for the work, they don’t need to be held accountable for doing their jobs.

Many organizations have put quite a bit of effort into various initiatives to hold people accountable, often with dismaying results. After an initial improvement in whatever measure they’re trying to hold people accountable for achieving (patient or customer satisfaction, productivity, or sales, for example), things go back to the way they were before the program. Sometimes, they even get worse.

The following sections spell out seven reasons why a focus on accountability can end up being counterproductive.

Reason #1: Accountability implies irresponsibility

When you tell people that you’re going to hold them accountable for something, it sends a subtle but unmistakable message that you don’t believe they can be trusted to hold

themselves accountable. The IRS holds people accountable for filing their taxes by April 15 because it knows that they can’t be trusted to do it voluntarily. But no one needs to be held accountable for making it to the dock on time to board a cruise ship. Homeowners mow their lawns because they have pride of ownership; renters need to be held accountable for hiring someone else to cut the grass. People who take pride in their work, their organizations, their professions, and themselves don’t need to be held accountable for memorizing a script to provide great customer service or compassionate patient care. They do it because they are intrinsically motivated, not because someone is forcing them or coercing them.

Reason #2: Holding people accountable can be exhausting

It takes a lot of management energy to hold people accountable. The more time and energy a manager must spend holding people accountable, the less time and energy that manager has for the more creative and productive work of leadership. You can think of it as “accountability fatigue.”

Reason #3: Accountability focuses on rules, not on values

People cannot be held accountable for commitment, enthusiasm, passion, pride, or caring. These qualities must come from an inner conviction, an intrinsic sense of ownership. You don’t hold people accountable for living values; you hold them accountable for following rules. When people share in a common set of values, you don’t need to set a lot of rules. The Nordstrom department store chain is famous for customer service excellence. In HR circles, the company is also famous for its two-sentence policy manual, which simply says: “At Nordstrom we only have one rule. Use good judgment in all situations.” Nordstrom employees don’t need to be held accountable for going above and beyond the terms of their job descriptions. They do it because they have taken ownership of the work.

Reason #4: Accountability is always after the fact and often demotivating

You empower people to do the things that need to be done in the future; you hold people accountable for the things that have, or have not, been done in the past. You can empower a nurse to practice at the top of her professional capabilities, and you hold her accountable when she fails the test. You can motivate a salesperson to make calls; you hold him accountable for not making those calls. Imagine going home at the end of the day and saying to your family: “Today I was held accountable for. . . .” Can you think of anything—anything at all—that would allow you to finish that sentence in a way that would make your family proud of you and motivate you to go to work tomorrow with a little more swagger in your step?

An excessive focus on accountability can be particularly harmful when it comes to performance appraisals—especially if the appraisals are performed only quarterly or, worse, annually, or if the evaluating manager has a span of control that is too large to allow a truly valid assessment. “Annual reviews,” note Cappelli and Tavis (2016), “hold people accountable for past behaviors at the expense of improving current performance and grooming talent for the future, both of which are critical for organizations’ long-term survival.”

Reason #5: You cannot hold people accountable for loyalty

Ownership is, we’ve come to believe, the “secret sauce” that the most successful organizations have. It both creates a sustainable competitive advantage for recruiting and retaining great people and for earning the lifelong loyalty of customers. These organizations earn what loyalty expert Fred Reichheld (2003) calls barnacles, or, in other words, “customers who are likely to stick around for a lifetime” (p. 88). You cannot hold either employees or customers accountable for being loyal to the organization—that only comes from a spirit of ownership.

Reason #6: Excessive focus on accountability can provide an incentive to cheat

More than 40 years ago, sociologist Donald Campbell and economist Charles Goodhart concluded from research in their own professions that when a performance measure is turned into a performance target, it ceases to be a good measure, largely because it can inadvertently incentivize perverse behavior. This syndrome shows up repeatedly in the organizational world: Managers at Sears auto repair shops selling people muffler systems that they didn’t need; Wells Fargo agents establishing bank accounts and credit cards for people who didn’t request them; and Veterans Health Administration managers falsifying appointment wait-time records—the examples are endless.

Reason #7: Accountability will never take an organization from good to great

If you read

Fortune magazine’s annual listings of America’s most admired companies and America’s 100 best companies to work for, you will see that not one of these organizations earned a place on these rosters by promoting a culture of accountability. To be sure, they all have standards of behavior and performance to which people are held accountable, but they all appreciate that these are minimal standards—they are the price of entry for being in business. Going from good to great requires a culture of ownership.

A note from Joe

A note from Joe

When I was an inpatient for one week at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics with acute diverticulitis, four registered nurses were primarily responsible for my care. By the time I was discharged, I had completed four nominations for DAISY Awards, one for each of those nurses. (Participating hospitals encourage patients to nominate nurses who go above and beyond the call of duty—see more at

www.daisyfoundation.org.) Not one of those nominations was completed because the nurse was doing an excellent job at something she could be held accountable for, something included in the RN job description. In each case, it was for going above and beyond the basic elements of the job description—of doing the sorts of things that people who own the work will do that people who are “renting a spot” on the organization chart will not do.

Summary

In its most common usage, the word “accountability” refers to the top-down accountability of reward and punishment. A culture that depends upon hierarchical accountability is subject to unintended consequences that can harm service quality and productivity. Cultural accountability is the peer-to-peer process of employees holding each other accountable for certain standards of behavior. For better or worse, it is often more influential than hierarchical accountability. The highest level is personal accountability, where employees hold themselves accountable and do not need bosses or coworkers looking over their shoulders. Personal accountability is the basis for a culture of ownership, which is one of the most powerful sources of competitive advantage an organization can gain.

Chapter Questions

- Which of the three levels of the accountability continuum is most prevalent in your organization?

- Which of the three levels of the accountability continuum do you respond to? Which do you personally find to be most motivating—hierarchical, cultural, or personal?

- Within your organization (or your family), which activities are most appropriately managed by hierarchical, cultural, and personal accountability?

- How far along on the journey from accountability to ownership is your organization, and what can be done to move it further along?

Joe Tye, MHA, MBA, is chief executive officer and head coach of Values Coach Inc., which provides consulting, training, and coaching on values-based leadership and cultural transformation.

Bob Dent, DNP, MBA, RN, NEA-BC, CENP, FACHE, FAAN, is senior vice president, chief operating officer, and chief nursing officer at Midland Memorial Hospital in Midland, Texas. In addition to membership in Sigma, he is 2018 president of the American Organization of Nurse Executives board of directors.

Information on purchasing Building a Culture of Ownership in Healthcare: The Invisible Architecture of Core Values, Attitude, and Self-Empowerment.

Building a Culture of Ownership in Healthcare was awarded first place in the 2017

AJN Book of the Year Awards in the Professional Issues category and also earned a five-star review from Doody's Review Service.

See “

Needed: Cultures of ownership,” an

RNL article by Bob Dent and Joe Tye.

References

Cappelli, P., & Tavis, A. (2016, Oct.). The performance management revolution.

Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from

https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-performance-management-revolution

Farson, R. E., & Keyes, R. (2003).

The innovation paradox: The success of failure, the failure of success. New York, NY: Free Press.

Reichheld, F. (2003).

Loyalty rules: How today’s leaders build lasting relationships. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.